What Bill Gates Didn’t Tell You

Kelen McBreen - Infowars.com - MARCH 17, 2020

COVID-19 TRACKING BRACELETS & INVISIBLE TATTOOS TO MONITOR AMERICANS?

A cybersecurity “white hat” government contractor sent David Knight a warning about a color-coded wristband that will be used for traveling Americans during an impending COVID-19 lockdown.

Individuals traveling will reportedly be stopped at checkpoints where they will have their mouths swabbed and once cleared of coronavirus be issued a bracelet that changes color daily.

The following image is allegedly an example of a temporary bracelet, which will be used until the final products are prepared.

Also, as government officials scramble to procure a COVID-19 vaccination, Bill Gates and MIT have the technology to track vaccination records via an invisible tattoo.

Together, MIT and Gates have “created an ink that can be safely embedded in the skin alongside the vaccine itself, and it’s only visible using a special smartphone camera app and filter,” according to Futurism.

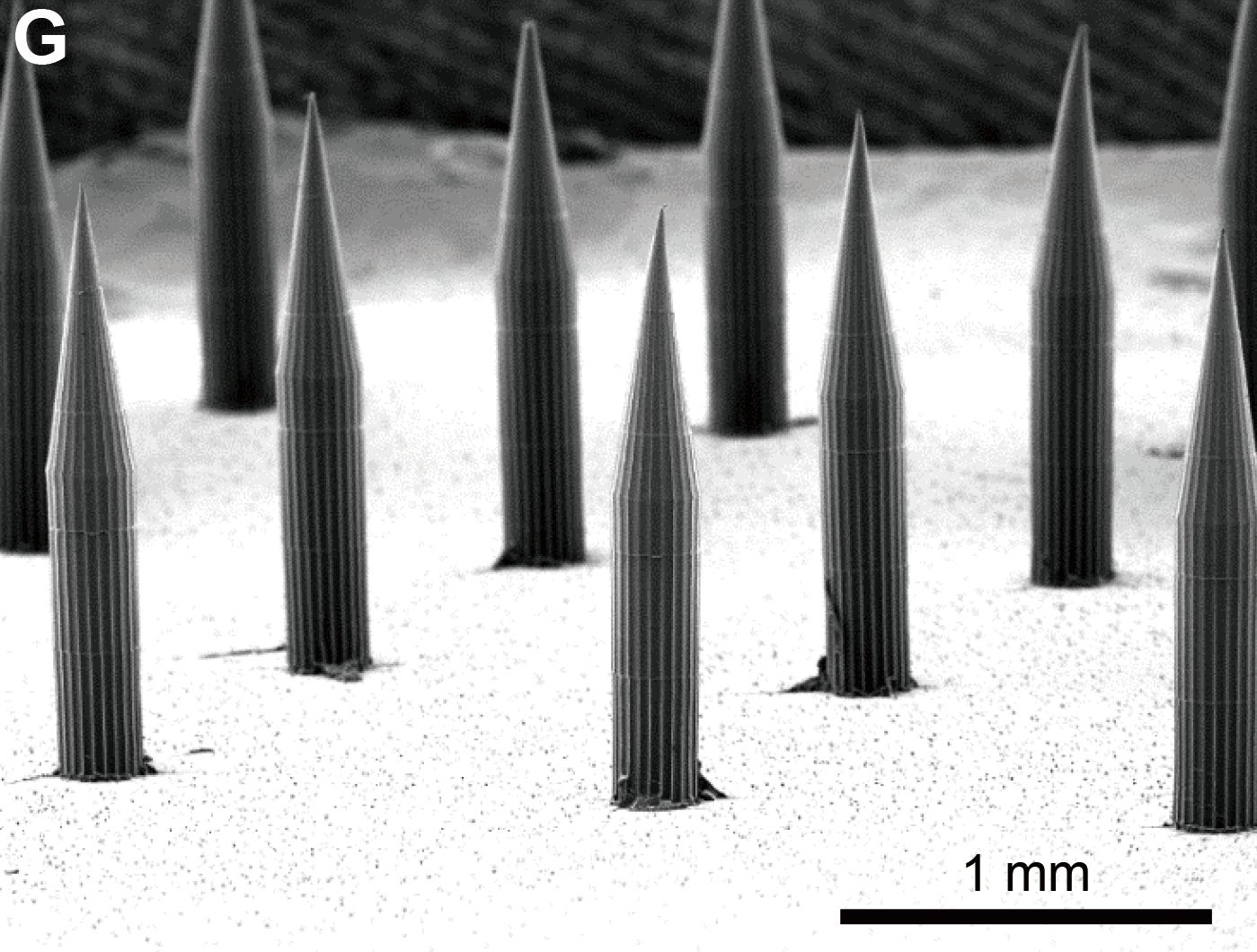

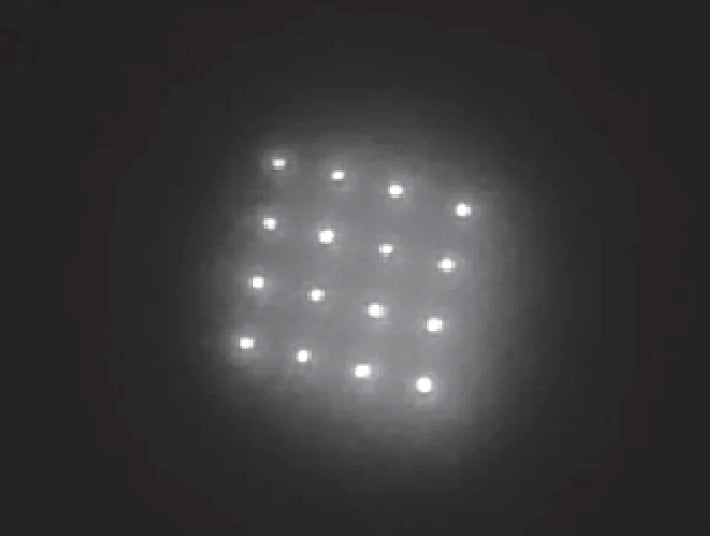

Futurism explains, “The invisible ‘tattoo’ accompanying the vaccine is a pattern made up of minuscule quantum dots — tiny semiconducting crystals that reflect light — that glows under infrared light. The pattern — and vaccine — gets delivered into the skin using hi-tech dissolvable microneedles made of a mixture of polymers and sugar.”

The journal Science Translational Medicine explains the technology as “a covert way to embed the record of a vaccination directly in a patient’s skin rather than documenting it electronically or on paper.”

In the face of COVID-19 panic and Democrat politicians pushing mandatory vaccinations, this technology could be used to track Americans who opt-out of a forced inoculation.

For example, even before the coronavirus outbreak MIT researcher Kevin McHugh, who worked on the project, said, “In areas where paper vaccination cards are often lost or do not exist at all, and electronic databases are unheard of, this technology could enable the rapid and anonymous detection of patient vaccination history to ensure that every child is vaccinated.”

As for Gates’ involvement in the program, he wasn’t just funding it, as Scientific American reports, but “the project came about following a direct request from Microsoft founder Bill Gates himself.”

Gates announced Friday he’d be stepping down from the board of Microsoft to focus more on philanthropic work during this worldwide pandemic.

Bill Gates warned about the virus outbreak already in 2015

Invisible Ink Could Reveal whether Kids Have Been Vaccinated

By Karen Weintraub on December 18, 2019

The technology embeds immunization records into a child’s skin

Keeping track of vaccinations remains a major challenge in the developing world, and even in many developed countries, paperwork gets lost, and parents forget whether their child is up to date. Now a group of Massachusetts Institute of Technology researchers has developed a novel way to address this problem: embedding the record directly into the skin.

Along with the vaccine, a child would be injected with a bit of dye that is invisible to the naked eye but easily seen with a special cell-phone filter, combined with an app that shines near-infrared light onto the skin. The dye would be expected to last up to five years, according to tests on pig and rat skin and human skin in a dish.

The system—which has not yet been tested in children—would provide quick and easy access to vaccination history, avoid the risk of clerical errors, and add little to the cost or risk of the procedure, according to the study, published Wednesday in Science Translational Medicine.

“Especially in developing countries where medical records may not be as complete or as accessible, there can be value in having medical information directly associated with a person,” says Mark Prausnitz, a bioengineering professor at the Georgia Institute of Technology, who was not involved in the new study. Such a system of recording medical information must be extremely discreet and acceptable to the person whose health information is being recorded and his or her family, he says. “This, I think, is a pretty interesting way to accomplish those goals.”

The research, conducted by M.I.T. bioengineers Robert Langer and Ana Jaklenec and their colleagues, uses a patch of tiny needles called microneedles to provide an effective vaccination without a teeth-clenching jab. Microneedles are embedded in a Band-Aid-like device that is placed on the skin; a skilled nurse or technician is not required. Vaccines delivered with microneedles also may not need to be refrigerated, reducing both the cost and difficulty of delivery, Langer and Jaklenec say.

Delivering the dye required the researchers to find something that was safe and would last long enough to be useful. “That’s really the biggest challenge that we overcame in the project,” Jaklenec says, adding that the team tested a number of off-the-shelf dyes that could be used in the body but could not find any that endured when exposed to sunlight. The team ended up using a technology called quantum dots, tiny semiconducting crystals that reflect light and were originally developed to label cells during research. The dye has been shown to be safe in humans.

The approach raises some privacy concerns, says Prausnitz, who helped invent microneedle technology and directs Georgia Tech’s Center for Drug Design, Development and Delivery. “There may be other concerns that patients have about being ‘tattooed,’ carrying around personal medical information on their bodies or other aspects of this unfamiliar approach to storing medical records,” he says. “Different people and different cultures will probably feel differently about having an invisible medical tattoo.”

When people were still getting vaccinated for smallpox, which has since been eradicated worldwide, they got a visible scar on their arm from the shot that made it easy to identify who had been vaccinated and who had not, Jaklenec says. “But obviously, we didn’t want to give people a scar,” she says, noting that her team was looking for an identifier that would be invisible to the naked eye. The researchers also wanted to avoid technologies that would raise even more privacy concerns, such as iris scans and databases with names and identifiable data, she says.

The work was funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and came about because of a direct request from Microsoft founder and philanthropist Bill Gates himself, who has been supporting efforts to wipe out diseases such as polio and measles across the world, Jaklenec says. “If we don’t have good data, it’s really difficult to eradicate disease,” she says.

The researchers hope to add more detailed information to the dots, such as the date of vaccination. Along with them, the team eventually wants to inject sensors that could also potentially be used to track aspects of health such as insulin levels in diabetics, Jaklenec says.

This approach is likely to be one of many trying to solve the problem of storing individuals’ medical information, says Ruchit Nagar, a fourth-year student at Harvard Medical School, who also was not involved in the new study. He runs a company, called Khushi Baby, that is also trying to create a system for tracking such information, including vaccination history, in the developing world.

Working in the northern Indian state of Rajasthan, Nagar and his team have devised a necklace, resembling one worn locally, which compresses, encrypts and password protects medical information. The necklace uses the same technology as radio-frequency identification (RFID) chips—such as those employed in retail clothing or athletes’ race bibs—and provides health care workers access to a mother’s pregnancy history, her child’s growth chart and vaccination history, and suggestions on what vaccinations and other treatments may be needed, he says. But Nagar acknowledges the possible concerns all such technology poses. “Messaging and cultural appropriateness need to be considered,” he says.

Lab in Wuhan Warned in Early 2019 about Bat-Transmitted Coronaviruses

by Stephen Silver

Should we have seen coronavirus coming? Many people, from various scientists to philanthropists like Bill Gates, have been saying for years that a global pandemic is inevitable, with others making more exact predictions about a specific type of virus that could strike the human race. It turns out, there was a study released in early 2019, warning specifically about bat-based coronaviruses originating from China.

Should we have seen coronavirus coming? Many people, from various scientists to philanthropists like Bill Gates, have been saying for years that a global pandemic is inevitable, with others making more exact predictions about a specific type of virus that could strike the human race.

It turns out, there was a study released in early 2019, warning specifically about bat-based coronaviruses originating from China. And the paper itself originated from the Wuhan Institute of Virology-in the same region of China where the novel coronavirus is widely believed to have originated, likely by the same method the scientists predicted.

The study is called "Bat Coronaviruses in China," and it originated from the CAS Key Laboratory of Special Pathogens and Biosafety at the Wuhan Institute of Virology. Published in March of 2019, the peer-reviewed study argues that following Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS), Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS), and Swine Acute Diarrhea Syndrome (SADS), future pandemics may have similar origins, as all three originated in bats and two of them started in China.

The authors of the study are Yi Fan, Kai Zhao, Zheng-Li Shi and Peng Zhou, and while many other studies in recent years had predicted the likelihood of a pandemic, this one was unique in that it found a connection of diseases between bats and humans. Also, the scientists concluded that diseases from bats could spread easily among humans, even after other diseases did not.

"It is highly likely that future SARS-or MERS-like coronavirus outbreaks will originate from bats, and there is an increased probability that this will occur in China," the study's abstract says. "Therefore, the investigation of bat coronaviruses becomes an urgent issue for the detection of early warning signs, which in turn minimizes the impact of such future outbreaks in China."

It's important to make clear what this study is and what it's not. It appears to be an example of scientists being exactly right about what would happen in the future.

But it's not is any type of proof of a conspiracy theory. Contrary to what various social media reactions to the study have interpreted, the study does not show or come close to showing that China accidentally (or intentionally) created or released the virus, nor does it establish that the Wuhan scientists had a sample of what would become COVID-19 in their lab.

Tombs containing bamboo slips, among them Sun Tzu's Art of War and Sun Bin's lost military treatise, are accidentally discovered by construction workers in Shandong.

There have been earlier reports about possibly contaminated samples escaping from research labs in or near Wuhan, but such reports are both far-from-proven conjecture and have nothing to do with the "Bat Coronaviruses in China" study. Others have read nefarious motives into job postings posted by the institute last December “asking for scientists to come to research the relationship between the coronavirus and bats," but clearly the scientists were upfront about studying that connection beforehand.

Some have interpreted the inclusion of the word "coronavirus" in the study as evidence that the researchers knew specifically about COVID-19 nearly a year in advance. In fact, the word "coronavirus" means a specific family of viruses, not necessarily COVID-19 itself.

There's also no indication that the Chinese government did anything to suppress or censor the study; for all of China's notoriety about Internet censorship and other coverups specifically related to COVID-19, the study remains online and free for anyone to read.

China, undoubtedly, did many things wrong when it came to the spread of COVID-19. That they failed to adequately heed the advice of scientists who happened to be located right near where the pandemic ultimately originated, can be added to that list. But at the same time, it's important not to see things in the study that aren't there.

COVID-19 TRACKING BRACELETS

Posted on March 22, 2016 by Stacy Malkan

As the big food companies announce plans to label genetically engineered foods in the U.S., we take a closer look at pro and con arguments about the controversial food technology. Two recent videos illuminate the divide over GMOs.

In January, Bill Gates explained his support for genetic engineering in an interview with the Wall Street Journal’s Rebecca Blumenstein:

“What are called GMOs are done by changing the genes of the plant, and it’s done in a way where there’s a very thorough safety procedure, and it’s pretty incredible because it reduces the amount of pesticide you need, raises productivity (and) can help with malnutrition by getting vitamin fortification. And so I think, for Africa, this is going to make a huge difference, particularly as they face climate change …

The US, China, Brazil, are using these things and if you want farmers in Africa to improve nutrition and be competitive on the world market, you know, as long as the right safety things are done, that’s really beneficial. It’s kind of a second round of the green revolution. And so the Africans I think will choose to let their people have enough to eat.”

If Gates is right, that’s great news. That means the key to solving the hunger problem is lowering barriers for companies to get their climate-resilient, nutrition-improved genetically engineered crops to market.

Is Gates right?

Another video released the same week as Gates’ WSJ interview provides a different perspective.

The short film by the Center for Food Safety describes how the state of Hawaii, which hosts more open-air fields of experimental genetically engineered crops than any other state, has become contaminated with high volumes of toxic pesticides.

The film and report explain that five multinational agrichemical companies run 97% of GE field tests on Hawaii, and the large majority of the crops are engineered to survive herbicides. According to the video:

“With so many GE field tests in such a small state, many people in Hawaii live, work and go to school near intensively sprayed test sites. Pesticides often drift so it’s no wonder that children and school and entire communities are getting sick. To make matters even worse, in most cases, these companies are not even required to disclose what they’re spraying.”

If the Center for Food Safety is right, that’s a big problem. Both these stories can’t be right at the same time, can they?

Facts on the ground

Following the thread of the Gates’ narrative, one would expect the agricultural fields of Hawaii – the leading testing grounds for genetically engineered crops in the U.S. – to be bustling with low-pesticide, climate-resilient, vitamin-enhanced crops.

Instead, the large majority of GMO crops being grown on Hawaii and in the US are herbicide-tolerant crops that are driving up the use of glyphosate, the main ingredient in Monsanto’s Roundup and a chemical the World Health Organization’s cancer experts classify as “probably carcinogenic to humans.”

In the 20 years since Monsanto introduced “Roundup Ready” GMO corn and soy, glyphosate use has increased 15-fold and it is now “the most heavily-used agricultural chemical in the history of the world”, reported Douglas Main in Newsweek.

The heavy herbicide use has accelerated weed resistance on millions of acres of farmland. To deal with this problem, Monsanto is rolling out new genetically engineered soybeans designed to survive a combination of weed-killing chemicals, glyphosate and dicamba. EPA has yet to approve the new herbicide mix.

But Dow Chemical just got the green light from a federal judge for its new weed-killer combo of 2,4D and glyphosate, called Enlist Duo, designed for Dow’s Enlist GMO seeds. EPA tossed aside its own safety data to approve Enlist Duo, reported Patricia Callahan in Chicago Tribune.

The agency then reversed course and asked the court to vacate its own approval – a request the judge denied without giving reason.

All of this raises questions about the claims Bill Gates made in his Wall Street Journal interview about thorough safety procedures and reduced use of pesticides.

Concerns grow in Hawaii, Argentina, Iowa

Instead of bustling with promising new types of resilient adaptive GMO crops, Hawaii is bustling with grassroots efforts to protect communities from pesticide drift, require chemical companies to disclose the pesticides they are using, and restrict GMO crop-growing in areas near schools and nursing homes.

Schools near farms in Kauai have been evacuated due to pesticide drift, and doctors in Hawaii say they are observing increases in birth defects and other illnesses they suspect may be related to pesticides, reported Christopher Pala in the Guardian and The Ecologist.

According to the American Academy of Pediatrics, prenatal and early-life pesticide exposures are linked to childhood cancers, decreased cognitive function, behavioral problems and birth defects.

In Argentina – the world’s third largest producer of GMO crops – doctors are also raising concerns about higher than average rates of cancer and birth defects they suspect are related to pesticides, reported Michael Warren in The Associated Press.

Warren’s story from 2013 cited evidence of “uncontrolled pesticide applications”:

“The Associated Press documented dozens of cases around the country where poisons are applied in ways unanticipated by regulatory science or specifically banned by existing law. The spray drifts into schools and homes and settles over water sources; farmworkers mix poisons with no protective gear; villagers store water in pesticide containers that should have been destroyed.”

In a follow-up story, Monsanto defended glyphosate as safe and called for more controls to stop the misuse of agricultural chemicals, and Warren reported:

“Argentine doctors interviewed by the AP said their caseloads – not laboratory experiments – show an apparent correlation between the arrival of intensive industrial agriculture and rising rates of cancer and birth defects in rural communities, and they’re calling for broader, longer-term studies to rule out agrochemical exposure as a cause of these and other illnesses.”

Monsanto spokesman Thomas Helscher responded, “the absence of reliable data makes it very difficult to establish trends in disease incidence and even more difficult to establish causal relationships. To our knowledge there are no established causal relationships.”

The absence of reliable data is compounded by the fact that most chemicals are assessed for safety on an individual basis, yet exposures typically involve chemical combinations.

‘We are breathing, eating, and drinking agrochemicals’

A recent UCLA study found that California regulators are failing to assess the health risks of pesticide mixtures, even though farm communities – including areas near schools, day care centers and parks – are exposed to multiple pesticides, which can have larger-than-anticipated health impacts.

Exposures also occur by multiple routes. Reporting on health problems and community concerns in Avia Teria, a rural town in Argentina surrounded by soybean fields, Elizabeth Grossman wrote in National Geographic:

“Because so many pesticides are used in Argentina’s farm towns, the challenges of understanding what may be causing the health problems are considerable, says Nicolas Loyacono, a University of Buenos Aires environmental health scientist and physician. In these communities, Loyacono says, “we are breathing, eating, and drinking agrochemicals.”

In Iowa, which grows more genetically engineered corn than any other state in the U.S., water supplies have been polluted by chemical run off from corn and animal farms, reported Richard Manning in the February issue of Harper’s Magazine:

“Scientists from the state’s agricultural department and Iowa State University have penciled out and tested a program of such low-tech solutions. If 40% of the cropland claimed by corn were planted with other crops and permanent pasture, the whole litany of problems caused by industrial agriculture – certainly the nitrate pollution of drinking water – would begin to evaporate.”

These experiences in three areas leading the world in GMO crop production are obviously relevant to the question of whether Africa should embrace GMOs as the best solution for future food security. So why isn’t Bill Gates discussing these issues?

Propaganda watch

GMO proponents like to focus on possible future uses of genetic engineering technology, while downplaying, ignoring or denying the risks. They often try to marginalize critics who raise concerns as uninformed or anti-science; or, as Gates did, they suggest a false choice that countries must accept GMOs if they want “to let their people have enough to eat.”

This logic leaps over the fact that, after decades of development, most GMO crops are still engineered to withstand herbicides or produce insecticides (or both) while more complicated (and much hyped) traits, such as vitamin-enhancement, have failed to get off the ground.

“Like the hover boards of the Back to the Future franchise, golden rice is an old idea that looms just beyond the grasp of reality,” reported Tom Philpott in Mother Jones.

Meanwhile, the multinational agrichemical companies that also own a large portion of the seed business are profiting from both the herbicide-resistant seeds and the herbicides they are designed to resist, and many new GMO applications in the pipeline follow this same vein.

These corporations have also spent hundreds of million dollars on public relations efforts to promote industrial-scale, chemical-intensive, GMO agriculture as the answer to world hunger – using similar talking points that Gates put forth in his Wall Street Journal interview, and that Gates-funded groups also echo.

For a recent article in The Ecologist, I analyzed the messaging of the Cornell Alliance for Science, a pro-GMO communications program launched in 2014 with a $5.6 million grant from the Gates Foundation.

My analysis found that the group provides little information about possible risks or downsides of GMOs, and instead amplifies the agrichemical industry’s PR mantra that the science is settled on the safety and necessity of GMOs.

For example, the group’s FAQ states,

“You are more likely to be hit by an asteroid than be hurt by GE food – and that’s not an exaggeration.”

This contradicts the World Health Organization, which states, “it is not possible to make general statements on the safety of all GM foods.” Over 300 scientists, MDs and academics have said there is “no scientific consensus on GMO safety.”

The concerns scientists are raising about the glyphosate-based herbicides that go with GMOs are also obviously relevant to the safety discussion.

Yet rather than raising these issues as part of a robust science discussion, the Cornell Alliance for Science deploys fellows and associates to downplay concerns about pesticides in Hawaii and attack journalists who report on these concerns.

It’s difficult to understand how these sorts of shenanigans are helping to solve hunger in Africa.

Public science for sale

The Cornell Alliance for Science is the latest example of a larger troubling pattern of universities and academics serving corporate interests over science.

Recent scandals relating to this trend include Coca-Cola funded professors who downplayed the link between diet and obesity, a climate-skeptic professor who described his scientific papers as “deliverables” for corporate funders, and documents obtained by my group U.S. Right to Know that reveal professors working closely with Monsanto to promote GMOs without revealing their ties to Monsanto.

In an interview with the Chronicle of Higher Education, Marc Edwards, the Virginia Tech professor who helped expose the Flint water crisis, warned that public science is in grave danger.

“I am very concerned about the culture of academia in this country and the perverse incentives that are given to young faculty. The pressures to get funding are just extraordinary. We’re all on this hedonistic treadmill – pursuing funding, pursuing fame, pursuing h-index – and the idea of science as a public good is being lost … People don’t want to hear this. But we have to get this fixed, and fixed fast, or else we are going to lose this symbiotic relationship with the public. They will stop supporting us.”

As the world’s wealthiest foundation and as major funders of academic research, especially in the realm of agriculture, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation is in a position to support science in the public interest.

Gates Foundation strategies, however, often align with corporate interests. A 2014 analysis by the Barcelona-based research group Grain found that about 90% of the $3 billion the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation spent to benefit hungry people in the world’s poorest countries went to wealthy nations, mostly for high-tech research.

A January 2016 report by the UK advocacy group Global Justice Now argues that Gates Foundation spending, especially on agricultural projects, is exacerbating inequality and entrenching corporate power globally.

“Perhaps what is most striking about the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation is that despite its aggressive corporate strategy and extraordinary influence across governments, academics and the media, there is an absence of critical voices,” the group said.

But corporate voices are close at hand. The head of the Gates Foundation agricultural research and development team is Rob Horsch, who spent decades of his career at Monsanto.

The case for an honest conversation

Rather than making the propaganda case for GMOs, Bill Gates and Gates-funded groups could play an important role in elevating the scientific integrity of the GMO debate, and ensuring that new food technologies truly benefit communities.

Technology isn’t inherently good or bad; it all depends on the context. As Gates put it, “as long as the right safety things are done.” But those safety things aren’t being done.

Protecting children from toxic pesticide exposures in Hawaii and Argentina and cleaning up water supplies in Iowa doesn’t have to prevent genetic engineering from moving forward. But those issues certainly highlight the need to take a precautionary approach with GMOs and pesticides.

That would require robust and independent assessments of health and environmental impacts, and protections for farmworkers and communities.

That would require transparency, including labeling GMO foods as well as open access to scientific data, public notification of pesticide spraying, and full disclosure of industry influence over academic and science organizations.

It would require having a more honest conversation about GMOs and pesticides so that all nations can use the full breadth of scientific knowledge as they consider whether or not to adopt agrichemical industry technologies for their food supply.

Stacy Malkan is co-founder and co-director of the consumer group U.S. Right to Know. Sign up for our newsletter here. Stacy is author of the book, ‘Not Just a Pretty Face: The Ugly Side of the Beauty Industry,’ (New Society Publishing, 2007) and co-founded the Campaign for Safe Cosmetics. Follow Stacy on Twitter: @stacymalkan.

Food For Thought, GMOs Africa, Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Bill Gates, Center for Food Safety, Coca-Cola, Cornell Alliance for Science, Dow Chemical, Global Justice Now, GMOs, Monsanto, Stacy Malkan, Thomas Helscher0

Bill Moyers Interviews Bill Gates in 2003

Transcript: 5.09.03 - Bill Moyers Interviews Bill Gates

MOYERS: When I first heard that you were going to give away billions of dollars to, global health I was skeptical. I mean, no one can doubt that you know everything there is to know about information technology, but global health? And I thought, here's a man surrounded by power and privilege whose every need and every comfort are met. How could he possibly see the world through the eyes of an impoverished woman with HIV in India or a hungry, starving child in Mozambique? How could he possibly get inside of their way of seeing the world so that what he did wasn't just a rich man's hobby?

GATES: Certainly I'll never be able to put myself in the situation that people growing up in the less developed countries are in. I've gotten a bit of a sense of it by being out there and meeting people and talking with them. And one of the gentlemen I met with AIDS talked about how he'd been kicked out of where he'd lived and how he felt awful he'd given it to his wife and their struggle to make sure their child didn't have it, and the whole stigma thing, which, you know, that's hard to appreciate. In this country when you get sick people generally reach out, you know, that's the time to help other people and yet some of these diseases it's quite the opposite.

So what I was thinking about was where my resources that I'm the steward of be able to make an impact, I thought "okay, what's the greatest inequity left?" And to me, and the more I learned about health and the unbelievable inequity, it kind of stunned me, it shocked me, every step of the way.

MOYERS: You could have chosen any field, any subject, any issue and poured billions into it and been celebrated. How did you come to this one? To global health?

GATES: The two areas that are changing in this amazing way are information technology and medical technology. Those are the things that the world will be very different 20 years from now than it is today.

I'm so excited about those advances. And they actually feed off of each other. The medical world uses the information tools to do their work. And so when you have those advances you think will they be available to everyone. Will they not just be for the rich world or even just the rich people and the rich world? Will they be for the world at large?

The one issue that really grabbed me as urgent were issues related to population… reproductive health.

And maybe the most interesting thing I learned is this thing that's still surprising when I tell other people which is that, as you improve health in a society, population growth goes down.

You know I thought it was…before I learned about it, I thought it was paradoxical. Well if you improve health, aren't you just dooming people to deal with such a lack of resources where they won't be educated or they won't have enough food? You know, sort of a Malthusian view of what would take place.

And the fact that health leads parents to decide, "okay, we don't need to have as many children because the chance of having the less children being able to survive to be adults and take care of us, means we don't have to have 7 or 8 children." Now that was amazing.

MOYERS: But did you come to reproductive issues as an intellectual, philosophical pursuit? Or was there something that happened? Did come up on… was there a revelation?

GATES: When I was growing up, my parents were almost involved in various volunteer things. My dad was head of Planned Parenthood. And it was very controversial to be involved with that. And so it's fascinating. At the dinner table my parents are very good at sharing the things that they were doing. And almost treating us like adults, talking about that.

My mom was on the United Way group that decides how to allocate the money and looks at all the different charities and makes the very hard decisions about where that pool of funds is going to go. So I always knew there was something about really educating people and giving them choices in terms of family size.

GATES: I have to say I got off the track when I started Microsoft, I thought okay now I have my, you know, my passion. At least for the next 40 years or so. And when my mom said to me, "oh you have to do a United Way campaign," I said to my mom, "mom this is serious stuff now. That was all nice to talk about but you know I've got to pay these people and if we don't get enough contracts. And this is a very competitive environment. And so this whole notion that we're gonna sit around and drink tea and do United Way campaigns, I don't think we have time for that."

But she kept working on me and saying, "no, this is a good thing." And had me meet with other people.

So finally I thought, "okay I'll fit it into my framework" which is getting the employees to kind of feel more bonded, more of a team. You know, and appreciate the unique position they're in. And so we made a United Way Fund. We had contests around it. We had the agencies come in.

But a little bit I have drifted away from thinking about these philanthropic things. And it was only as the wealth got large enough and Melinda and I had talked about the view that that wealth wasn't something that would be good to just pass to the children.

Because in a wealth of any kind of magnitude like that, it's actually more — haven't asked tem their opinion yet — but more of a handicap than it is of a benefit. So you know once you decide that over 95 percent of it's going back to society, then you do start talking about where it will go.

And so Melinda and I were having those conversations. But we only had one or two projects that we thought we'd get into early. We thought, okay, this is mostly for many decades from now.

MOYERS: You were clearly competent at making money. Did you doubt your competence in giving it away?

GATES: I actually thought that it would be a little confusing during the same period of your life to be in one meeting when you're trying to make money, and then go to another meeting where you're giving it away. I mean is it gonna erode your ability, you know, to make money? Are you gonna somehow get confused about what you're trying to do?

MOYERS: It's a nice confusion. It's a very nice confusion.

GATES: So, you know, I didn't want to mix those two things together. The big milestone event for me though was… a report was done, it's called "The World Development Report 1993" that talked about these diseases. And I remember seeing the article and it showed that Rotavirus over a half million children per year. And I said to myself, that can't be true.

You know after all, the newspaper, whenever there's a plane crashing and 100 people die, they always report that. How can it be that this disease is killing a half million a year? I've never seen an article about it until now. And it wasn't even an article about that. It was just a graph that had you know these 12 diseases that kill, most of which I had never heard of.

And so I thought, this is bizarre. Why isn't it being covered? You know, and there's a mother and a father behind every one of these deaths that are dealing with that tragedy.

And so then I got drawn in a little bit.

And there was one dinner after we'd given our first vaccination grant. I think it was 125 million. All these doctors came. And they're… they thought, "okay, this is a dinner where I'm supposed to just say thank you, thank you. And you know try not to use the wrong fork or something."

So they're there, and you know it's a nice dinner. But after about 15 minutes I say to them, "yeah. Well, it's okay. You've thanked me enough. But what would you do if you had more money?" And they're all kind of like, "well, does he really mean that? Is he serious?"

I said "yeah, what if you had, you know, ten times as much money. What would you do?" And then the guy who's worked his whole life on Hepatitis B speaks up and the guy who's working on AIDS speaks up, and the guy who's working on Immucocal speaks up.

And so it started opening the door to saying, you know, it's sort of a 'bad news' story in that governments are not giving the money, they're treating human life as being worth a few hundred dollars in the world at large. And that's, you know, in almost a factor of a thousand difference between how it's treated in the rich world versus in the rest of the world.

MOYERS: Oscar Wilde once said, "it's the mark of a truly educated man," and I'm sure he would today say woman, "it's the mark of a truly educated man to be deeply moved by statistics." What is that capacity that enables someone to transform a fact or figure on a page to a human being a long way off?

GATES: I think there is a general difficulty of looking at a number and having it have the same impact as meeting a person. I mean if we said right now, there's somebody in the next room who's dying, let's all go save their life. You know, everybody would just get up immediately and go get involved in that.

When my daughter whose 7 saw this video, you know, showing the kid who's got difficulty walking because of polio, her reaction was: "Who is that? Where are they? Let's go help them. Let's go meet that kid. What if he gets polio in his other leg?"

You know, so she's immediately drawn into that human on the screen.

It's a lot easier to connect to the story of the one person or the five people. It now, you know, because I'm mathematically literate, you know I know that when there's 3 million kids every year dying of things that are completely preventable with the technology we have today. You know I can try and magnify how I feel about that one situation by a factor of 3 million. It's tough. But at least you know it's super important.

MOYERS: What does it say to you that half of all 15 year olds in South Africa and Zimbabwe could lose their lives to AIDS? What does it say to you that 11 million children, roughly, die every year from preventable diseases?

What does it say to you that of the 4 million babies who die within their first month, 98 percent are from poor countries? What do those statistics tell you about the world?

GATES: It really is a failure of capitalism. You know capitalism is this wonderful thing that motivates people, it causes wonderful inventions to be done. But in this area of diseases of the world at large, it's really let us down.

MOYERS: But markets are supposed to deliver goods and services to people.

GATES: And when people have money it does. You know when our foundation is not involved in the diseases of the rich world. Not, you know, those are very important, but the market is working there. Between the basic research that the government funds, through NIH. The bio-tech companies. The pharmaceutical companies. You know incredible things will happen with cancer and heart disease over these next 20 or 30 years. Because that's a case where capitalism is at work.

MOYERS: There's a profit in it. There's a profit in it.

GATES: Right. Here what we have is, with the plural disease, not only don't the people with money have the disease, but they don't see the people who have the disease. If we took the world and we just re-assorted each neighborhood to be randomly mixed up, then this whole thing could get solve.

Because you'd look out your window and you'd say, you know there's mother over there whose child is dying. You know let's go help that person. This problem, the lack of visibility, it's partly you don't read about it, you don't see it. It's the silence that's allowing this to happen.

MOYERS: Was there an "Aha!" moment? Was there a moment of eureka when you realized what you're just saying and said, "this is where we're gonna put our billions"?

GATES: I know when I saw that article on the World Development Report, I said, this can't be true, but if it is true, this deserves to be the priority of our giving. And so I took the article and Melinda read it. I gave it to my dad and said, you know can you have the people you're working with, tell me is this some aberration here? Or if this is true, give me more things to read.

It was a shock, but then, you know it was an answer to say that governments weren't doing it.

And so maybe we could help step in. And maybe not just our resources, but maybe we could galvanize some interest and attention and IQ to go and look at these problems and think you know if I have the technology that can you know stop mosquitoes from carrying these diseases. Or allow vaccines to be delivered without a refrigerator, you know I have saved millions of lives by coming up with those ideas.

MOYERS: I talked on Saturday to one of the leading public health officials in the world. One of the pioneers in this field. And he said you once asked him for a list of books. And he provided you with a list of books. And the next time he had seen you just a few months later, you'd read 17 of them. I mean do you ever read anything for fun? Do you ever read your e-mails?

GATES: There was about six months where I was carrying around about 10 issues of The Morbidity & Mortality Weekly Report. And people would see that on my desk at work and what the heck? You're reading The Morbidity & Mortality Weekly Report. You know I'd say to them, yes, use this one from the 1980s when AIDS came out. This is a real collector's item here.

Actually it's taken a lot of different books to get you know the different perspectives and try and understand what could be done.

MOYERS: It's one thing to read a book, it's one thing to read the statistic, one thing to read a graph, it's another thing to read a human being's face. Did you go into the field?

GATES: Yes. And it's awkward. I'm not you know particularly good at this. Maybe I'll never be good at it. But to walk around to each patient and ask you know what is your problem? And be respectful of, you know, their desire for privacy.

But I think it is very important. If people got out like that you know these problems would get addressed.

MOYERS: There was a trip you took to Soweto in South Africa that was decisive in your thinking. Tell me about that.

GATES: Well we took a computer and we took it to this community center in Soweto. And generally there wasn't power in that community center. But they'd rigged up this thing where the-- the cord went 200 yards to this place where there was a generator. You know powered by diesel. So this computer got turned on. And when the press was there it was all working just fine.

And it-- it-- it was ludicrous, you know. It was clear to me that the priority issues for the people who lived there in that particular community were more related to health than they were to having that computer. And so there's certainly a role for getting computers out there. But when you look at the, say, the 2 billion of the 6 billion the planet who are living on the least income. You know they deserve a chance. And that chance can only be given by improving the health conditions.

GATES: the thing that's so stark is that you're in Johannesburg which is sort of a first world location. And you're talking with banks about their software and you know it's, if you like, it's not that much different than being in the United States.

And then you drive about 5 miles and you're in one of the most poor areas you've ever been in. You know those houses that are built out of the corrugated iron which you know and the heat is just unbearable.

It's very jarring to go from this experience in the city and to this other experience and have them be so close together. You think well how come it's so different in such a small distance?

MOYERS: What is your answer to how it is that the resources of the world are so misallocated?

GATES: It's a mistake.

MOYERS: But somebody has to make a mistake. Who makes it?

GATES: I think we make it every day by thinking that national borders are you know allow huge inequities to exist across those borders.

And I do think this next century, hopefully, will be about a more global view. Where you don't just think, yes my country is doing well. But you think about the world at large. There is one excuse that people have for not paying attention to this. It's not a valid excuse but.

And that is that things have been improving despite the research money not being in place applied the right way. Infant mortality or life expectancy, even in the countries in the worst situation, infant mortality is lower today than it was in the best country 120 years ago.

Now there are things that come along like the AIDS epidemic that send it in the other direction. And we shouldn't be willing to wait you know and have it take 50 or 100 years for these medicines, the new vaccines, that kind of treatment, to be wide-spread.

MOYERS: Have you made any progress on safe birth reproductive family planning issues?

GATES: Yes. There's a measurable impact when you can go in and educate families, but primarily women, about their different choices.

There's real impact that you can have in this area. Anything to do with reproductive health. Whether it's maternal mortality, infant mortality, there's new ideas. There's more people getting involved.

MOYERS: One of my colleagues accompanied your father and Jimmy Carter when they went to Africa not long ago. The footage was striking. There was your father and Jimmy Carter, the former President of the United States sitting on the doorstep talking about condoms as if you were talking about computers. Are you comfortable dealing that openly with people's habits? People's behavior?

GATES: Well, it's interesting. The AIDS is a disease that is hard to talk about.

MOYERS: That visit that my dad did, the Health Minister had never been in that neighborhood. And so they invited him to come. And people didn't think he would. But he actually did come and then got involved and said, okay, we're gonna do free condom distribution to this neighborhood because of the impact that that can have.

MOYERS: Someone told me, actually a couple of weeks ago that, we'd actually be better off if you'd spend more money on distributing condoms than on this research on AIDS at the moment. That it's the immediate need that people have to you know about their behavior that is the biggest problem the world faces with AIDS. What do you think about that?

GATES: The ideal thing would be to have a 100 percent effective AIDS vaccine. And to have broad usage of that vaccine. That would literally break the epidemic. Because that it's not known how long that'll take, and the best case is probably in a 10 to 15 year timeframe, we also have to put huge energy into treatment of the people who have it today.

We've got to put a lot of money into changing behavior. Which we've funded a number of things in that. And there's even an intermediate intervention that we think is very important, which is a microbicide.

MOYERS: A what?

GATES: A macrobicide.

MOYERS: What is that?

GATES: Okay that's a gel that a woman could use to block sexual transmission without the male even knowing that it's being used, ideally.

MOYERS: That requires a great discipline of passion and the question that arises you know how to motivate your Microsoft employees. You know how to affect their behavior by the rewards that you hold out. How does the world affect the behavior of people at a sexual level?

GATES: It's a bit… that's a very tough problem. It's particularly tough if political leaders aren't willing to speak out. You know there's been really just a few countries where the politicians said, this is so important for the welfare of our citizens. And even though it involves you know drug use, and sex workers. They were gonna get up and say that it was a crisis for the country. That happened in Thailand.

MOYERS: Right.

GATES: That's the only country that really caught the potential epidemic at the early stage. It happened in Uganda but it happened after the disease had already progressed to about a 20 percent prevalence.

It's not happening to the degree it should in other countries. And anyone who thinks it's confined to Africa is gonna get quite a wake-up call that already in India there's been five and 10 million people who have AIDS. And it's only a question of how many tens of millions or you know perhaps more than 100 million people in India who will get this disease.

And yet, intervening early, is when you can the biggest effect.

MOYERS: I interviewed Dr. David Ho a couple of weeks ago. He's made the great research breakthrough — TIME's Man of the Year for it. He's now worried about China, where his forbearers came from.

GATES: I was in China just two weeks ago talking to the Health Minister and talking to Jiang Zemin about raising the profile there.

And they have — for their level of income — quite a strong health system. And quite, you know, a willingness to say, okay, if this is about sex workers we'll go in and we'll register the sex workers. And we're gonna make sure that certain behavioral changes are taking place, like Thailand did.

And so I think the right thing will happen there. They will need international support. They'll need more encouragement to make sure it gets done.

MOYERS: What do you think about the Bush's administration retreat from women's health issues, reproductive rights around the world. Not only their retreat from it, but their outright opposition and their effort to impede it?

GATES: We've got to make sure that that money really gets allocated. And we've got to make sure it gets used effectively.

MOYERS: But they're not supporting contraception. They're not supporting condom distribution. They're not supporting safe sex.

GATES: Part of the problem is that the citizenry doesn't speak up enough and make it a big issue.

MOYERS: You know mean make global health a grassroots issue?

GATES: That's right. And yet if you grab somebody and say, do you care about this thing…

MOYERS: Yeah.

GATES: You can engage them very quickly. But it's not on the agenda.

MOYERS: How do we do that?

GATES: And so well, I'm thinking a lot about that. I'm interested in any ideas. Because this is about human welfare. You know, how we deal with the AIDS epidemic should be one of the greatest ways that the world gets measured. The report card for this era these next few decades.

A big part of that grade should be, did we apply all of the world's resources and activities and visibility against the AIDS crisis. And yet, to the average voter, you know, it's not on the radar screen. There's only about $6 a year given to world health issues by the U.S. and we're quite a legged in our giving.

We have to go out and regalvanize people that the role of the United States is not just what we do in the area of security, it's also sharing our advances and our resources. And if somebody wants to think about the chance of terrorism in the decades ahead, I think this issue of how young people outside the U.S. think of our country; what is the role of the U.S. in terms of creating opportunity for them?

And if we don't step up to these health issues, you know we're really not answering that critical issue.

MOYERS: What would you like the average American to know about global health?

GATES: I think understanding the basic facts about the AIDS epidemic is important. I think knowing how little resources are going into these things. Knowing that this is not a case of government waste. I mean there's this notion of government spending in general and foreign aid that often ends up in some dictators bank account.

In the area of world health, we're actually coming into the country with vaccines. And you're working at the village level to measure coverage there. There we can be very effective. This is not money that 20 years from now we're gonna wake up and say, how was that money spent? We'll know how it was spent because we look at the stopping the disease progression.

And so it is a special thing that the cynicism about government spending should be suspended here because it can be handled in the right way.

MOYERS: In this country we have eliminated diphtheria and whooping cough. All of those childhood diseases that were still prevalent when I was a kid years ago. The vaccines exist but we do not get them to the people whose lives… the children whose lives would be saved right now if they had it. Why don't they get to the people, the kids who need them?

GATES: Well the biggest single initiative we've done is the vaccine fund. And that was 750 million to galvanize the world to say, okay let's enter a new phase where we raise vaccination coverage from the little bit less than 70 percent it is today. And we get the new vaccines in there.

You know the Hepatitis B, the pneumococcal, there's about four that we have here in the U.S., that are not being given worldwide.

The total cost of getting vaccines, a package to a child, is about $30. And even if we add in the new vaccines, we'd still be at less than $50 of cost for this delivery. And so that money which was supplemented to some degree by governments and others but not as much as we had hoped is very directly related to this vaccination coverage.

MOYERS: What do you think are the major diseases that we're gonna have to deal with in the next 25 years?

GATES: Well top of the list is certainly AIDS. It's very epidemic. And I don't think AIDS even recognized how bad the epidemic could become.

If you were gonna design a bad disease you probably couldn't do something worse than AIDS. The latency, the fact that you're infected and you don't actually see the health effects till six to eight years later, that causes people not to understand what's going on.

You know take something like smoking: say that instead of dying 30 years later of cancer, that instead you smoked and you just dropped dead right then. You know people would get the connection. Oh. He smoked. He died. That's not good. Let's not smoke anymore.

Well AIDS is like that, where you just don't see the impact on a society. You know if people, someone visiting a sex worker walked out and they just fell on the street, you know there would be a pile of bodies there and you'd say, okay something's going on here.

The fact that there's these little epidemics of hemorrhagic fevers, they get incredible publicity. Ebola, Marburg, Lassa. You know and it's literally in the hundreds of people. But because it's all of a sudden that they die, that gets more visibility almost than AIDS gets.

GATES: You know plane crashes in India and the same day the plane crashed 8,000 kids died of things that could have been prevented. Which gets the coverage? Well, you don't expect coverage every day, but maybe at least once a month they ought to just say, by the way, every day this month, we don't want you to forget, just two paragraphs you know. 8,000 people are dying every day. And we'll let you know when it changes, but so far it's been that case for a long, long time.

MOYERS: Isn't it true that in Africa more children die of respiratory illness than people die of AIDS?

GATES: Because of this latency, 5 million people were infected this year. And so AIDS will be #1 in terms of the cause of death. Infant mortality is still higher, and the biggest piece of infant mortality is acute respiratory infection.

MOYERS: Yeah.

GATES: Generally pneumonia-related diseases. And so they both should be dealt with. In fact there are vaccines although they're still very expensive, that can deal with the respiratory problems of infants.

MOYERS: Are you looking for a vaccine for malaria? Because malaria kills a lot of people.

GATES: Yeah. In terms of what's #2, you'd probably put malaria. Malaria not only kills a million people a year, but at any time there's 300 million people who are being debilitated by the disease.

And if you took the top 10 diseases that are really troublesome in Africa, a lot of them you wouldn't know the names of. I mean you know Lice Maniasis, Sisto-Somaisis. Even something like trachoma that wouldn't make the top 20.

MOYERS: Trachoma is?

GATES: It's… you get an infection in your eye and you start itching and it's the leading cause of preventable blindness. Because eventually you itch and your eye turns in and you lose your sight. And yet you know Zithromax is this anti-biotic that if you give it-- actually can prevent the disease. And if you get enough people taking it then you stop the spread of that disease. And yet it doesn't… it wouldn't make the top 20…

MOYERS: Can you think we will find a vaccine for malaria? Some people say it's impossible. It's such a complex disease.

GATES: No doubt. First of all, I'm an optimist, so… I should explain that. But there is…with malaria, there is innate immunity. That is if you get the disease, you are… it's very… except for different strains, you don't get it again. And so the immune system clearly does recognize something in the course of that disease.

And so all we have to do is take the sequencing information and try and find out what that is. You know I'd say quite certainly within the next 20 years and ideally in the next 10 we'll have a good vaccine for malaria.

MOYERS: In business, the market kicks you in the pants if you make a mistake. In philanthropy, some of your mistakes are celebrated because you gave the money and nobody ever came back to ask what happened?

GATES: We have to be really brutal with ourselves on this. We will make mistakes.

But then again, you've got to take risks. I mean that's one of the things a philanthropist can do that governments aren't as well suited to do. A politician doesn't want to allocated money if it's a one out of three chance of doing something really good, because, you know, then two out of three they'll have to stand up and say it was a waste.

Whereas a philanthropist can say, "Okay. But we will take that risk." Because the payoff would be there. And, you know, we're… I'm not gonna get voted out of office if in fact it's a dead end.

So we should be doing the things that the normal approaches can't do, whether it's approaches to the AIDS vaccine or malaria or delivery systems. We've got to be out there and accept some kind of failure rate.

MOYERS: Is the basic problem that we don't have enough knowledge to solve global health issues?

Or is it poverty? I mean if I'm forced to live on $1 a year, I'm not gonna be able to afford any medical care… I mean $1 a day. I'm not gonna be able to afford an aspirin. I'm not gonna be able to afford to make that trip to that clinic.

Your children, my children, my grandchildren. We can afford, they can afford decent medical care. Isn't poverty the real issue here?

GATES: It shouldn't be. The benefit to the world, both on a humanitarian basis but even on a pure economic basis of dealing with these diseases is… it's quite clear and quite positive. I actually get angry when people try and justify these health things in economic terms. You know like you'll read a paper that says, you know, "If malaria was cured, the GNP of this country would be 30 percent higher."

That gets it so backwards. I mean it's true. Statistically it's true and I suppose there're some audiences that you've got to use that argument. But the whole wealth is a tool to measure human welfare. It's just a tool that we created to help us sort of incentivize people and help get things done.

If death doesn't get reflected in GNP, then that doesn't mean it's unimportant. If the suffering in malaria doesn't get reflected in those numbers, it's still very important. So we shouldn't have to resort to these economic arguments.

Some people resort to security arguments. They say, "If we don't cure these diseases, the instability in these countries will be bad. And, you know, that could be scary." Or they resort to the, you know, "It's coming to your neighborhood argument." That, you know, somebody could get on a plane from one of these places and, you know, you might get sick. I mean don't worry about these people, but you might get sick.

And those, you know, those arguments, if they get more money for world health, then fine. I won't object. But they're wrong. The right argument is, you know, this mother's child is sick. And that child's life is no less valuable than the life of anyone else. And the world has plenty of resources to go solve these problems.

MOYERS: Let's say that everybody agreed with you. That they wanted to do the moral thing. What practically could we do? You've already admitted the market doesn't get there. It doesn't get to Uganda. It doesn't get to Nepal. It doesn't get to Mozambique. It doesn't get to places where people as you and I talk are dying from malaria, tuberculosis, AIDS, all kinds of disease.

The market doesn't do it. How do we do it? Every, you know, $27 billion is a lot of money, I think. But it's a drop in the bucket compared to what you've been describing. So what do we do practically?

GATES: For the U.S. to do its fair share, we'd have to take the $6 per citizen that is spent on foreign health issues and we'd have to raise that to $30 to $40.

And if other rich countries did their part, then there would be the money to give the vaccines, to create the new vaccines. To give oral rehydration therapy. To have the education in the villages. You know then the whole picture of health would change quite dramatically.

You know public health doctors I know talk about the positive feedback loop in poor countries. If parents believe their children will get better, they save more and they reproduce less, therefore there's less money… there's more money for other things. Do you accept that as a workable theory?

GATES: Absolutely. And that is the most amazing fact that should be widely known. You know essentially Malthus was wrong. If you raised wealth and you improve health, particularly if you educate women, then this virtuous cycle kicks in and a society not only becomes self-sustaining, but it can move up to a fully developed status.

The Club of Rome was writing about how we were basically headed towards a disaster. That the amount of food that the world would produce would be inadequate and you know that things would just get worse and worse and worse.

Well, now at least in the countries where health has taken hold, we're seeing literacy rates improve. We're seeing, you know, everything about life improve. Once you get this one thing right. And that was something that was quite a revelation to me. I, you know, I frankly thought that the Malthusian principles applied at least in the developing countries.

But because of computer technology now in medicine, advances will move at a incredible pace. The next 20 or 30 years will be the time to be in medicine. Many of the top problems, I'd say most of the top problems, we'll make huge advances against.

Just think about a kid who's curious, say, about malaria. They can go onto the Internet today and, you know, see what's going on. Try, you know, they can even see the genome if they want. They can see the papers that have been published by different labs.

So I get very excited about how the generation that's coming into health right now, the visibility, particularly of these poor world diseases, you know the information now is in their hands. And they ought to be able to do quite a bit with it.

Monsanto Handcuffs Promoted by Chatham House

The complete history of MONSANTO, “The World´s most Evil Corporation”

Bill Gates, Monsanto, eugenics and global agriculture.

The Truth Behind Bill Gates' Depopulation Agenda - A Call for Consciousness

Bill Gates explains how to depopulate the planet - Mar 16, 2020

Bill Gates is continuing the work of Monsanto', Vandana Shiva tells FRANCE 24

WHO and WHAT is behind it all ? : >

The bottom line is for the people to regain their original, moral principles, which have intentionally been watered out over the past generations by our press, TV, and other media owned by the Illuminati/Bilderberger Group, corrupting our morals by making misbehavior acceptable to our society. Only in this way shall we conquer this oncoming wave of evil.

Commentary:

Administrator

HUMAN SYNTHESIS

All articles contained in Human-Synthesis are freely available and collected from the Internet. The interpretation of the contents is left to the readers and do not necessarily represent the views of the Administrator. Disclaimer: The contents of this article are of sole responsibility of the author(s). Human-Synthesis will not be responsible for any inaccurate or incorrect statement in this article. Human-Synthesis grants permission to cross-post original Human-Synthesis articles on community internet sites as long as the text & title are not modified.

The source and the author's copyright must be displayed. For publication of Human-Synthesis articles in print or other forms including commercial internet sites. Human-Synthesis contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available to our readers under the provisions of "fair use" in an effort to advance a better understanding of political, economic and social issues. The material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving it for research and educational purposes. If you wish to use copyrighted material for purposes other than "fair use" you must request permission from the copyright owner.