Brazil's reforms hang in the balance/amp

HUMAN SYNTHESIS

email: humansynthesis0@gmail.com

##Brazil's reforms hang in the balance

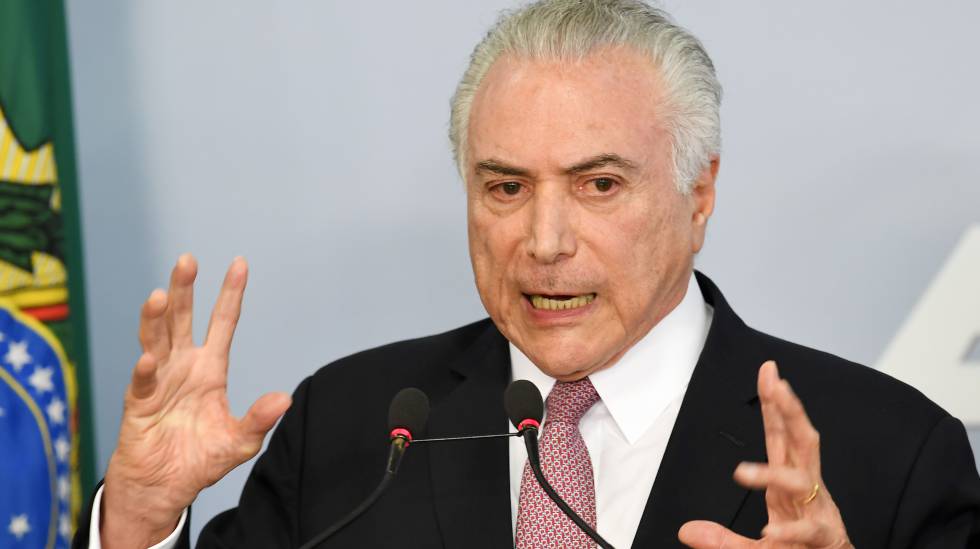

Mick Bowen - Keywords: reforms Michel Temer Brazil

Daily Brief - Sep 21, 2017

Deeply unpopular and tangled in a web of political turmoil, Michel Temer's chances of executing tough, investor-friendly reforms appear to be shrinking. Now the Brazilian president has a narrow window to straighten out the country’s troubled fiscal position ahead of the 2018 elections

"Brazil is back," Wellington Moreira Franco, one of President Michel Temer’s most loyal lieutenants, said at a business forum in May.

Indeed, Brazil has reasons to cheer. The country has pulled free of recession. Action by the central bank has sent inflation rates tumbling and interest rates falling. And the president is advancing a multi-focus reforms agenda, including pushing through new labour laws and a cap on fiscal spending.

But few are quite as bullish as Moreira Franco, secretary general of the presidency. Deeper reforms will be needed to get Brazil’s economy on a footing to compete with other emerging markets. Investors want to see Latin America’s largest economy execute a turnaround, but it is unclear whether Temer, hobbled by a weak political standing and deeply unpopular with voters, will be able to make it happen.

Temer's already-abysmal public approval took a further beating in May when he was caught on tape apparently discussing hush money payments with Joesley Batista, an executive from JBS, the country’s largest meatpacking company. Temer was up against a wall. He had to assure a jittery market that he had no intention of resigning, and his administration tried to play politics.

"The president’s efforts aim to avoid the political issues that could jeopardize the drive for reform and the creation of an investment-friendly business environment," Moreira Franco said at the time.

Much of the political turbulence has since subsided and the president has been able to advance his agenda. In July, as corruption allegations dogged Temer, and Moreira Franco, for that matter, the Senate passed a labour reform bill that aims to cut business costs, despite opposition from trade unions. The following month, Congress voted against putting Temer on trial on charges of taking $12 million in bribes from JBS.

But the president’s weak standing, both in Brasília and in the public eye, had suffered a harsh blow. He had not been particularly popular when he took office. Just 13% of Brazilians approved of his administration in July 2016, when he stepped in after the impeachment of former President Dilma Rousseff, according to the polling firm Ibope. But it got worse. Temer’s popularity rating sank to just 5% this past July.

When Temer took office, the business community was optimistic that he would deliver on promises to restore economic growth. Temer stoked investor hopes by proposing a series of reforms to get the country’s budget deficit under control. He also appointed a pragmatic economic team that included a former central bank governor, Henrique Meirelles, as finance minister.

Temer has put his weight behind passing the reforms, deemed as a necessary if bitter, remedy for an ailing economy. Unencumbered by the expectations of the next election, Temer was supposed to push forward with unpopular measures, such as raising taxes and cutting spending.

But a technocratic approach that mixes market-minded economic policies and backroom politics can only go so far.

Meirelles has said the fiscal reforms could move through Congress before the end of the year. But a growing number of economists think Temer will leave the issue for his successor. The delay has frustrated the market, especially with the next presidential election still over a year away.

"What is disappointing is not the fiscal outcome, although we would have preferred stronger numbers for sure. What is disappointing is that up to now, the government has not passed social security reform, and Congress does not seem to be totally convinced of the urgency to do so," says Mario Mesquita, chief economist at Itaú Unibanco.

"The market has lowered its hopes of what to expect," says Alberto Ramos, co-head of the Latin America economic research team at Goldman Sachs.

Why are the Brazilians protesting

From BBC 7 June 2017

Sluggish recovery

After a two-year recession – the economy shrank 3.9% in 2015 and dropped another 3.6% in 2016 – Brazil has eked out muted growth rates in the first half of 2017. The economy beat forecasts in the second quarter, but GDP only rose 0.3% year-on-year, helped by a bump in consumer spending. The government predicts GDP will grow just 0.5% in 2017.

Although unemployment remains high, it came in at a lower-than-expected 12.8% in July, as the economy added jobs for the first time since August 2015. That growth, however, came more from the informal economy and the public sector than salaried employment in the private sector, Ramos says. "Stability is not good enough. We need to find ways to grow," he says.

"It is a modest recovery, especially considering how deep the recession was," says Arminio Fraga, the former central bank president, who now leads the investment management firm Gávea Investimentos in Rio de Janeiro.

Indeed, despite growth tilting up marginally, other economic indicators remain listless. Productivity in Brazil, which was already low by international standards, fell by 4.8% between 2014 and 2016, according to research by the Fundação Getulio Vargas (FGV). Meanwhile, investment levels tumbled 26% and could decline another 3% this year, FGV says.

"The drivers of growth are not as strong as they used to be," says David Beker, chief Brazil economist and fixed-income strategist at Bank of America Merrill Lynch in São Paulo. The bank forecasts Brazil’s economy will expand by 0.25% in 2017 and 1.5% in 2018.

But the worst may be over. The precipitous fall in investments stemmed in part from the troubles faced by the state-owned energy company Petrobras, wracked by the Lava Jato, or Car Wash, bribery investigation. But now Petrobras has started to turn around, which could help investments levels recover, according to Mesquita. "This provides a bit of a cushion in macroeconomic terms," he says.

The Instituto de Pesquisa Econômica Aplicada (IPEA), the government’s own economic research organization, sees a slight increase in investments in the coming months, propped up by the private sector.

"Investment has remained weak, and there is the influence of the ongoing scandals," Beker says. "Consumers are already leveraged, but we expect the strong decline in interest rates is going to help growth."

Other economists share the optimism. Although Brazilian businesses want to see faster action from the president, the Temer administration has passed reforms, including a cap that limits the growth of federal government spending to the rate of inflation for at least 10 years.

"Reforms are back on the agenda," Beker says. "It is something [the government is] going to pursue in the coming months."

Reforms, especially a social security overhaul that includes increasing the average retirement age from 54 years old, are crucial for Brazil to grow in the coming years, according to members of the president’s economic team. Inflation has already dipped below the 4.25% target, and the central bank has cut the Selic, its overnight lending rate, below 10% for the first time in four years. It aims to get it below 8% by the end of the year.

"Structural interest rates in Brazil were at 5% in real terms in the past few years," Central Bank President Ilan Goldfajn told journalists in August. "They were 10% in previous decades. Now they are around 3% or 3.5%. The importance, in the long run, is that we will be able to reduce neutral rates, and for that, we need the reforms. Real interest rates are now at a low level, historically speaking. We believe the lower borrowing rate can stimulate the economy."

The drop in inflation has lent more credibility to Brazil’s monetary policy, says Fraga, who had appointed Goldfajn as economic policy director at the central bank in 2000.

"Given our sad inflation history, the achievement is quite remarkable, and it has allowed significant interest rate cuts," Fraga says. "The massive recession has played a role, but the central bank deserves a lot of credit for the solid anchoring it has provided. Markets have responded well so far, but further and sustainable gains will require significant reductions in political uncertainty and long-term fiscal imbalances."

Debt pile mounts

Despite the improvements in growth, employment and inflation, official statistics show that Brazil’s fiscal profile has gone from bad to worse. The country’s net debt-to-GDP ratio stood at 73.8% by July, up from 51.5% at the end of 2013. The average ratio among emerging markets, according to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), was 47.4% in 2016.

And the debt pile is only set to get higher. The IMF expects Brazil’s net debt to rise to 87.8% of GDP in 2022, even if pension reforms are enacted. Economists at Santander are more glum, forecasting Brazil’s net debt to equal 92% of GDP in three years. Even the Brazilian government admits the ratio will keep rising until at least 2020, with the first budget surplus not coming before 2021.

"If you look at the size of the Brazilian government, it’s big," says Beker. "If you look at the deficit, it’s big. If you look at the primary deficit, it’s big. We need a tighter fiscal policy to have a more relaxed monetary policy."

The goal, according to Planning Minister Dyogo Oliveira, is to turn the primary deficit before interest rate payments from 2.5% of GDP into a surplus of the same magnitude. "This is the size of the task that Brazil needs to achieve over the next 10 years," he says.

Regardless, the government increased the budget deficit target for this year and next to 159 billion reais ($50.9 billion), up from an initial estimate of 139 billion reais for 2017, due to lower-than-expected tax revenues.

Yet it is public spending that will make lowering the deficit most difficult, Oliveira says. "Public spending has had a vertiginous rise over the past years, from 14% of GDP to almost 20%. Now, we will have to bring spending back to 17% of GDP," he says. "We are currently spending 57% of the federal budget on pensions, nearly 435 billion reais. We are using resources to pay pensions and have very little to invest."

Fraga calls Brazil’s debt load a "relevant vulnerability," but doubts the government can reduce spending to 17% of GDP in 10 years. "Even if social security reform, in particular, gets done, I have a hard time seeing it," he says. "It is all quite impressive but in practice, it means a back-loaded fiscal adjustment, so the debt ratio is certain to keep on rising."

Mesquita says turning the deficit into a surplus hinges on the pension reforms. "The main pillar of [the government’s] strategy, which is spending limits in the medium term, is something that it will not be able to deliver if it doesn’t pass pension reform."

Moving targets

Reforming a state pension system is controversial anywhere, and in Brazil, it is arguably even more complicated. With a myriad of centrist parties, called the centrão, or the big centre, clamouring for compensation in return for voting against pursuing Temer’s corruption charges, Congress is sharply fragmented. If it does debate the proposed pension reforms, it is likely to water down the bill from its original form, says Marcelo Carvalho, chief economist for Latin America at BNP Paribas.

That dilution has already started. The initial proposal would have saved the government around 2% of GDP per year over 10 years. As the bill went through congressional committees, that fiscal saving was dialled back to around 1.2%. More negotiations will likely reduce the impact on the budget even more, to around 0.5% to 1% of GDP, Carvalho says.

"Simply put, reform is inevitable. If the current government does not get it done, then the administration taking office in 2019 will have to do it – but then probably in a harsher version to make up for lost time," Carvalho says.

The rate at which the social security costs are rising illustrates the urgency, increasing by almost 50 billion reais in the past year alone, almost twice as much as the budget for the government’s infrastructure investment program, known as the Programa de Aceleração do Crescimento or PAC.

Yet social security is no longer the most pressing concern in Congress. Electoral reform, which has to go to a vote before the 2018 election, has drawn the attention of lawmakers. Congress could also delay a vote on the Temer administration’s plans to replace the loan subsidies from the national development bank BNDES with costs closer to market rates.

In the meantime, the government doubled the tax on gasoline in July, looking to raise money to offset the deficit. "The gas tax hike shows the political strength that the economic team has to meet the fiscal targets for this year," Carvalho says.

Still opportunities to invest

Given the political uncertainty, investors are looking for the government to unload tangible assets, particularly through a privatization and infrastructure concessions program. The government earned 3.72 billion reais in fees in March, when it auctioned four airport concessions to European bidders. More airport concessions, including Congonhas in São Paulo, could go to auction, and the government’s Investment Partnerships Program, or PPI, is slated to grant contracts for hydroelectric dams and oil and gas exploration blocks in late September.

The administration also plans to privatize 57 state-owned businesses, including the federal utility company Eletrobras and the national mint. Eletrobras, which has accumulated losses of 228 billion reais over the past 15 years, according to the asset management company 3GRadar, has attracted interest from the local units of EDP – Energias de Portugal and Engie of France. The government could earn an estimated 20 billion reais from the sale of part of its 51% stake in Eletrobras.

"Fiscal pressures are the main reason behind the sale," says a former government official, referring to the budget deficit. "The fiscal issue is so strong that it may help overcome the reluctance of some politicians towards privatization."

Carla Junqueira, a partner at the law firm Mattos Engelberg in São Paulo, says the "ambitious" privatization program will have a positive impact on the economy, even if only some of the 57 firms are sold. "In spite of the negative aspects surrounding Temer himself, the economic stance of his government is very responsible," she says.

While the fire sale could jumpstart investor interest, the bigger impact on Brazil’s future could come from the reforms. "It is not going to be the reform we may have dreamed of but it is going to be what is possible for now," says José Guilherme Souza, a partner at the investment firm Vinci Partners in Rio de Janeiro. "To me and to many people I have been talking to, the main focus is politics, rather than economics. That is the uncertainty that undermines investment flows."

But Alexandre Schwartsman, an economist and the former director of international affairs at the central bank, warns against the complacency that he says has crept into the Brazilian market. Investors are cutting Temer slack as a result of their benign view on emerging markets, he says. The next president will need to cut public spending – and there is no guarantee that he or she will achieve greater success than the current administration or even pick up Temer’s politically unpalatable reform agenda.

"The market seems too quiet," Schwartsman says. "People feel that liquidity will come this way whatever happens." LF

WHO and WHAT is behind it all ? : >

Commentary:

Administrator

HUMAN SYNTHESIS