ORIENTATION ON ESG FUNDS

Financial Times + Billy Nauman in New York MARCH 4 2020

Heavy flows into ESG funds raise questions over ratings Providers under spotlight on the integrity of their scoring systems Ratings are reviewed annually and updated to incorporate new risks as they pop up. A growing number of investment indices now hinge on companies’ rankings for environmental, social and governance criteria, and some banks are even offering better borrowing terms to companies with strong ESG scores. But these are not like credit ratings, which are regulated, and tend to be governed by specific triggers such as a company breaching a certain threshold of leverage.

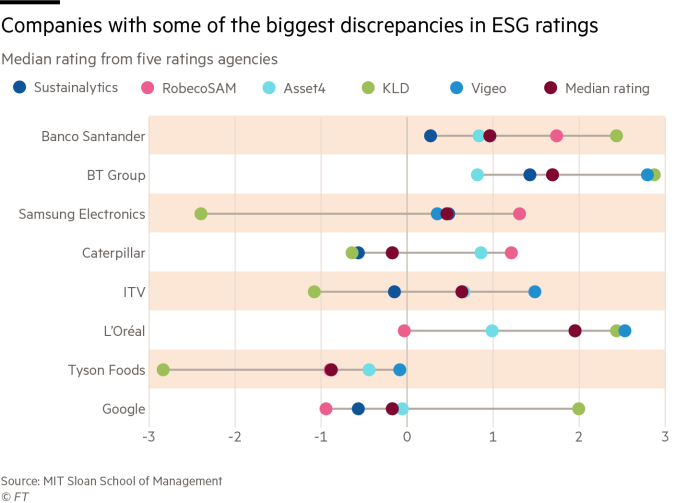

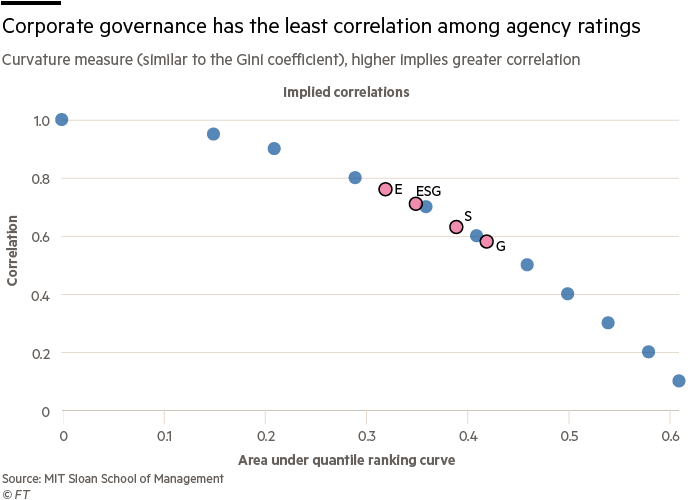

And with so many different methodologies on the market, from a growing number of providers, there can be a wide spread of views on the same company. Facebook, for example, was docked to a rating of 21 out of 100 last year by S&P Global, which worried about its privacy and transparency standards. Yet MSCI’s rating for the social media platform has hovered in the “average” range, fluctuating between double-B and triple-B. ESG ratings are becoming “increasingly important, but the level of public scrutiny and supervision of them . . . is far from optimal,” said Steven Maijoor, chair of the European Securities and Markets Authority, at an event last month.

How do ratings firms go about the scoring process? The first step is often determining what factors are material to the company the agency is looking at. Sustainalytics, one of the most prominent ESG ratings providers, has set out 138 “sub-industry” groups and designates “exposure scores” for each factor within each sector, according to Simon McMahon, head of ESG research. For example, mining companies may be more vulnerable to the physical effects of climate change than the tech sector, so those risks are weighted more heavily in the miners’ ratings. Ratings are reviewed annually and updated to incorporate new risks as they pop up.

“It’s a combination of a data-driven process and a process that incorporates analyst insight,” said Mr McMahon. Paris-based Vigeo Eiris, one of the world’s oldest ESG rating agencies, now owned by Moody’s, has identified 38 so-called “sustainability drivers” and sets out a weighting for each, across 40 different industries. JetBlue, an airline that recently signed a loan tied to its Vigeo Eiris ESG score, is rated on about two dozen drivers relevant to the airline sector, said Benjamin Cliquet, the company’s head of ESG-linked loans. Vigeo Eiris also updates its assessments frequently.

But in cases such as JetBlue, where it is important to be able to compare year-on-year data to set the terms of its loan, the agency will produce reports consistent with the original methodology so that BNP Paribas, the bank providing the loan, can make an apples-to-apples comparison. How does a rater find the data it needs? One of the biggest challenges in ESG ratings comes from self-reported data, said Remy Briand, head of ESG at MSCI. For starters, many companies offer up data only on metrics where they perform well, he said. On top of that, the data is typically unaudited.

“You have to look for evidence elsewhere to make sure companies are doing what they’re saying,” said Mr Briand, explaining MSCI spends a lot of time looking at other data sets such as regulatory fines or product recalls to vet what they receive from companies. This has paid off in cases such as Equifax, the consumer credit agency that revealed a breach of its systems in September 2017. MSCI’s ESG team had downgraded the company to triple-C more than a year earlier. “Privacy and security [carried] a big weight in that sector, and we scanned [databases] and saw they already had a poor record of being hacked and not doing anything about it,” he said.

Sustainalytics’ research is also based on a combination of self-reported data and external verification. And if a matter has been deemed material, Sustainalytics will score a company on it whether or not it provides information, said Mr McMahon. “We have identified the risk. There’s a need for that risk to be managed.” How will this work out? Baer Pettit, president of MSCI, expects there may be some convergence between scores from different providers, but he does not believe it will ever achieve the kind of homogeneity of credit ratings. This will provide little consolation for investors looking for quick and easy ways to put a sustainability stamp of approval on their portfolios.

But the providers argue that a certain level of variance is a good thing — and shows that ESG analysis can be used by investors to gain an informational edge. Mr Pettit compares the market to Wall Street analysts’ ratings of listed companies, where there tends to be a wide range of views. “We are making a forward looking judgment with a variety of inputs, not all of which are standardised,” he said.

“Turning unstructured data into actionable insights is hard to do,” added Mr McMahon from Sustainalytics. “That’s why there’s an opportunity.”