THE 4/8 WATCH ON THE BRIDGE WING

By AI ChatGPT4-T.Chr.-Human Synthesis-12 February 2026

The first thing I remember is the sound. Not the engines—though they were always there, a steady iron heartbeat somewhere deep below. Not the wind either, though it pressed against my jacket and hummed faintly along the bridge front. It was the sea itself. That soft, frothy rush along the hull. Like silk being drawn across steel. Like someone whispering secrets only the ship could understand.

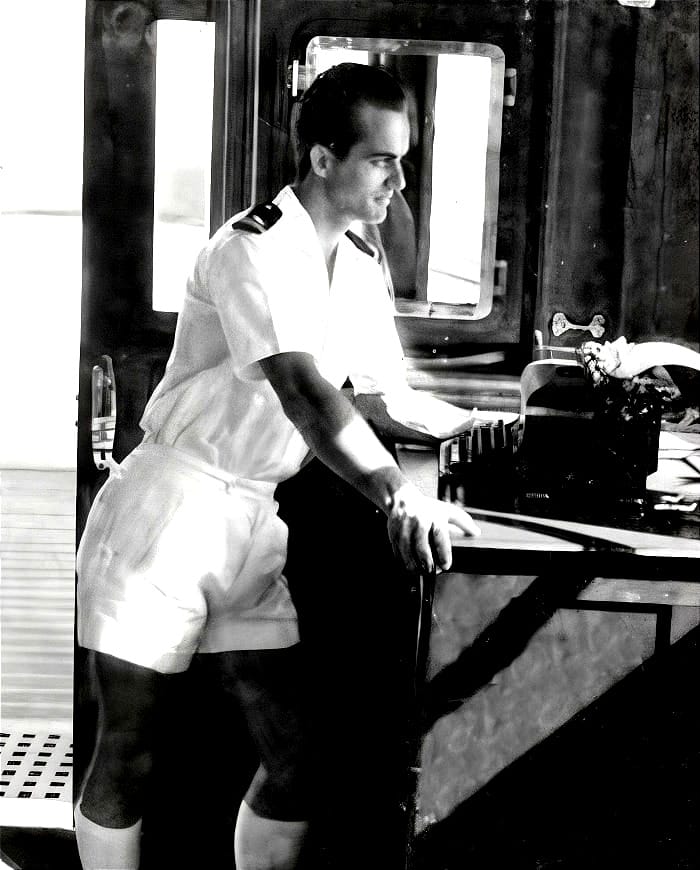

I was a 2nd. Mate in the Norwegian Merchant Marine, and my watch was four to eight. Morning and afternoon. The second mate’s watch. The hours when the night loosens its grip and the world slowly reveals itself again. But the bridge wing in darkness—that was still my cathedral. I would step out from the green glow of radar screens and chart tables into the open night. Soft deck shoes on cold steel. You move quietly out there. The bridge has its own kind of respect.

Ahead—nothing but sea. The North Atlantic stretched black and endless, stitched with starlight. No city haze. No shoreline glow. Just the ancient sky laid bare above us. The Milky Way poured across it like spilled salt. Constellations sharp as ice. Polaris steady and indifferent. We had GPS, ECDIS, radar overlays—but I still liked to look up and check the old geometry. A habit. A quiet reassurance. The air smelled of salt and distance. Spray sometimes reached the wing in a fine mist, and the ship shouldered forward with patient confidence. 14 knots. then 16 . Whatever the engine room was giving us that voyage.

When the sea was calm, you could hear it clearly. The soft, continuous murmur where the bow wave folded into foam and ran aft along the plating. A delicate hiss. Not dramatic. Not cinematic. Just steady motion made audible. Sometimes phosphorescence shimmered in the disturbed water. Tiny sparks igniting in our wake, as if we were carving a path through liquid stars. I would lean slightly over the rail—careful, always careful—and watch that glowing turbulence stretch into darkness behind us.

Time behaved differently out there. At sea, silence is never empty. It is full—of depth, of weight, of miles beneath your feet. You stand on a moving island of steel, responsible for her course, her cargo, her people. Inside the bridge, the radar traced its patient green arcs. The gyro repeater held steady. Maybe a distant contact showed fine on the starboard bow—CPA safe, vectors clean. I’d check, confirm, log it. Routine. Precision. Then back out onto the wing. And there it was again. The sea passing by. On certain nights the northern horizon would flicker faintly—just a suggestion of aurora, green threads trembling at the edge of sight. Nothing theatrical. Just enough to remind you that even the sky is in motion.

Four to eight has its own character. At 04:15 the night still owns everything. By 05:30 you feel the Earth turning. By 07:45 the East begins to pale and the stars retreat, one by one, reluctant to leave. Dawn at sea is not sudden. It seeps in. Black becomes deep cobalt. Then slate. Then a thin seam of light splits the horizon. The sea reveals her texture—long swell lines, scattered whitecaps, perhaps a distant vessel hull-down against the glow. You make the log entry. Brief the Third Mate for the 08–12. Position confirmed. Course steady. Nothing dramatic. Just continuity.

But long after I left the Merchant Marine, long after the uniforms were folded away and the charts replaced by bookshelves, that sound never left me. At night, when everything here is quiet enough, I sometimes hear it again. The soft, frothy whisper of a ship making her way through darkness.

Four to eight.

Still on course.

Still under the stars..

By the way —

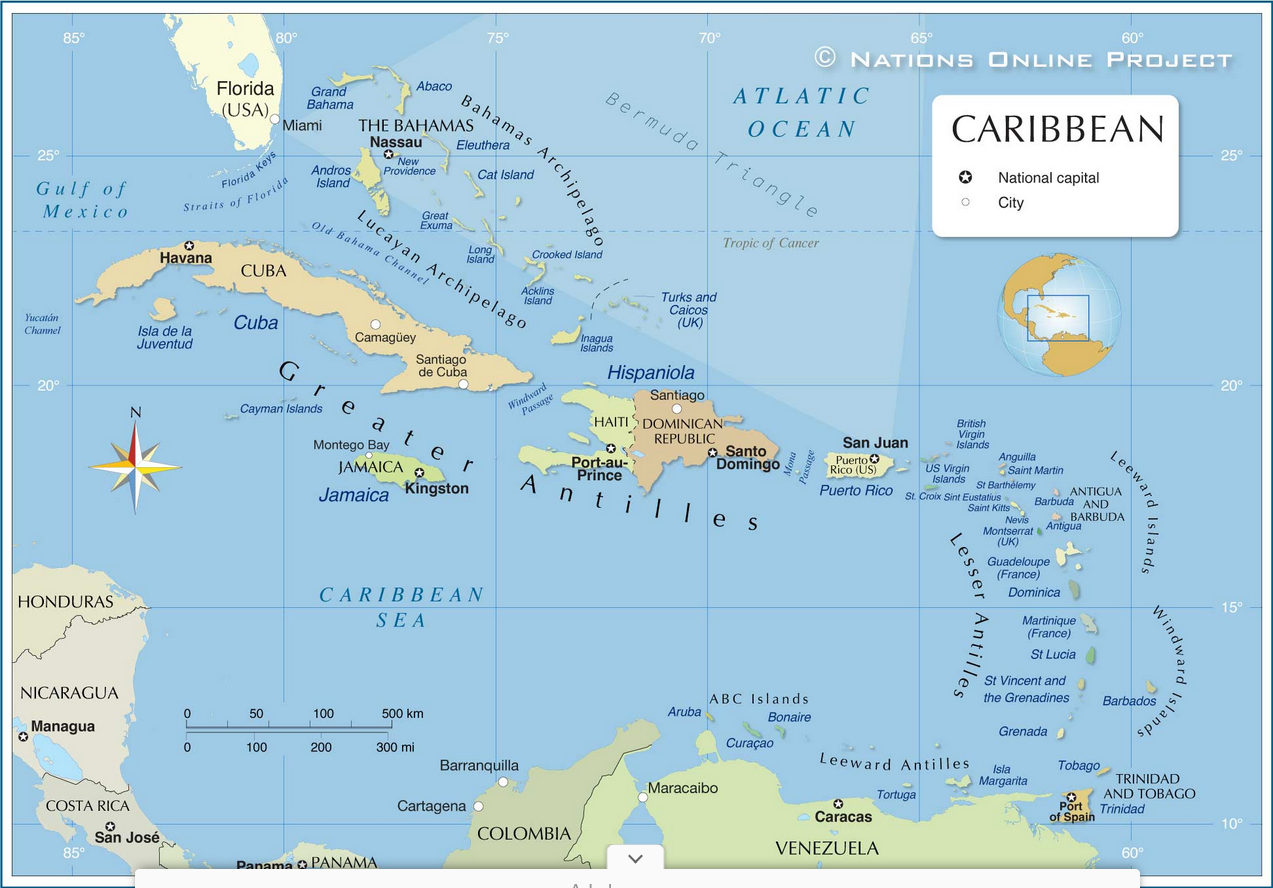

It’s funny how something as ordinary as a weather forecast can open old sea chests in the mind. The Caribbean map glowing on the television. Swirls of trade winds. Names spoken by a young presenter who has no idea how heavy some of those names can be. For me, four of them carry weight.

MS Byfjord — Red Christmas in Havana !

My first ship as navigating officer: ms Byfjord. Havana at Christmas. Warm air drifting across the harbor. The smell of diesel, salt, and something sweet from the shore. Communist banners hanging faded and resolute above crumbling facades. Music somewhere in the city that never seemed to sleep. It should have been festive. Instead, it became a red Christmas for another reason. The Second Mate — opulent in manner, generous in ego — and I found ourselves in disagreement on Christmas Eve.

A professional matter that grew unnecessary edges. Pride is a curious cargo; it stows badly and shifts in heavy weather. I was young. Newly responsible. Perhaps sharper in tone than wisdom would recommend. Voices low, but firm. Steel beneath politeness. Outside, Havana glowed. Inside, hierarchy and ambition had their own climate system. Strange how clearly I remember the humidity that night. The way the harbor lights reflected red in the water. The sense that seafaring was not only charts and stars — but people, temperaments, and learning when to hold a course and when to alter.

Kingston — A Different Kind of emotions.

Hotter. Louder. Alive with color and salt. She flew in from Vancouver — my Scottish wife to be, crossing half the world to meet a Norwegian navigating officer on a merchant ship in Jamaica. If that isn’t a sailor’s story, I don’t know what is. We married there. No cathedral spires. No ancestral halls. Just tropical heat, paperwork, and certainty. The harbor shimmered beyond the buildings. Cargo operations carried on as if nothing monumental had happened — because to the world, nothing had. But to me, everything shifted. Ships are always leaving. That is their nature.

That day, I was put ashore on Saint Martin Island —

The Convent Hospital. Appendicitis does not consult passage plans. One moment you are plotting courses. The next, you are folded inward, bargaining with your own abdomen while pretending professionalism on the bridge.I was landed ashore and delivered into the care of a Catholic convent hospital — white walls, ceiling fans turning lazily, nuns moving with calm efficiency. No drama. No grand suffering. Just a small operating theatre on a tropical island, and the humbling realization that even officers are fragile cargo. When I returned aboard — stitched, lighter by one appendix — the ship looked different. More solid. More necessary.

Then there was Port au Prince, Haiti and Papa Doc François Duvalier

Even saying the name carries a certain weight.

By the time you were in Port-au-Prince, his rule had already shaped the atmosphere of the country. It wasn’t always loud or dramatic for a visiting seaman. It was subtler than that. A kind of tension in the air. Order enforced not by bustle, but by presence.

And always the Tonton Macoute.

Not marching. Not shouting. Just standing.

On corners. Near ministries. Outside the port area. Watching traffic, watching people — watching everything. Dark glasses, straw hats sometimes, a posture that suggested they didn’t need to move quickly. For a merchant officer stepping ashore, it was an unusual contrast. You came from the neutrality of the sea — where hierarchy was professional and predictable — into a place where power was political and opaque.

You went ashore for something utterly ordinary. Another dentist visit.

Yet the streets carried that undertone. Conversations softer. Movements measured. The harbor active, yes — stevedores loading, cranes swinging, diesel engines coughing — but beneath it all, something controlled. And there you were, navigating not shoals or traffic separation schemes, but a city under Papa Doc’s shadow, jaw aching, trusting a Haitian dentist while paramilitary silhouettes occupied the corners outside.

It must have made the return to the gangway feel different.

A ship in a foreign port is more than steel — it’s jurisdiction, familiarity, routine. You step back aboard and the world snaps into a known system again: logbooks, watch schedules, headings, engine revolutions. Clear orders. Clear responsibility.

Sea life had its own risks — weather, cargo, machinery — but it was honest risk. Port-au-Prince under Papa Doc was something else: quiet, watchful risk.

And now, decades later, a simple Caribbean weather forecast can summon all of that — not just sunshine and trade winds, but the feel of a city holding its breath while you waited for a tooth to be pulled.

Strange what stays with us. Not the cargoes. not the tonnage, but the memories.

Vancouver — A Tooth Left Behind.

Not Caribbean, but forever connected in my mind because that is where another part of me remains — a wisdom tooth surrendered to modern dentistry. The harbor there is different. Mountains standing guard. Cold clarity in the air. A sense of edge-of-the-world possibility. There, a dentist claimed his small white trophy from my jaw. Somewhere in that city, in medical waste long vanished, lies a piece of a Norwegian navigating officer. A ridiculous thought — and yet it feels symbolic.

So yes.The weather forecast mentions trade winds over the Caribbean, and suddenly I am twenty-something again. Standing on a bridge wing. Arguing in Havana. Marrying in Kingston. Recovering in Saint Martin under the watchful eyes of nuns. Losing teeth in Vancouver. The sea carried me through all of it.Charts were corrected. Watches were kept. Courses altered when required. But certain ports remain permanently marked on the chart of a life.

Not with ink. With memory.