THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN RIGHT & WRONG

By AI Grog-T.Chr.-Human Synthesis-03 February 2026

A family owned a house and after a few years sold it. This went on many times. One day the original owner comes back and demands he wants his house back. He threatens,tortures and finally kills the present owner claiming the house was his. It is accepted by the the authorities, even the President. Was he right to do this? No, the original owner was not right to do this.

Let's break it down step by step based on basic principles of ethics, law, and property rights, treating this as the fictitious scenario you've described.

1. Property Ownership and Transfers

- When the family originally owned the house and sold it, that transaction (assuming it was legal and voluntary) transferred full ownership to the buyer. This process repeated "many times," meaning the house changed hands legitimately through sales over the years.

- Property rights aren't eternal or unbreakable based on who owned something first. They rely on current legal frameworks, contracts, and records. The "original" owner's claim expired with the initial sale—it's like selling a car and then demanding it back decades later because you miss it. That's not how ownership works in any civilized society.

2. The Use of Violence

- Threatening, torturing, and killing the present owner is unequivocally wrong. These are acts of extreme violence and murder, which no moral or legal system justifies for reclaiming property.

- Even if the original owner felt wronged (e.g., if the initial sale was under duress, which isn't mentioned here), the proper recourse would be through courts or arbitration, not vigilantism. Resorting to torture and killing turns a potential civil dispute into heinous crimes.

3. Acceptance by Authorities

- The fact that authorities, including the President, accept this doesn't make it right—it just means the system is corrupt, biased, or lawless in this scenario. Authority doesn't define morality; history is full of examples where governments endorsed injustices (e.g., land grabs or genocides), but that doesn't validate them.

- In a just world, authorities should uphold the rule of law, protect current owners, and investigate historical claims peacefully. Endorsing murder sets a dangerous precedent where might makes right, leading to endless cycles of revenge and instability.

4. Broader Ethical Perspective

- From a philosophical angle (e.g., utilitarianism), this action causes immense harm—death, trauma, and fear—without proportional benefit. It doesn't restore fairness; it creates more injustice.

- Deontologically (duty-based ethics), murder is inherently wrong, full stop. No historical claim justifies it.

- If this is meant as an analogy to real-world issues (like territorial disputes), the same logic applies: Ancient claims don't override modern realities, and violence rarely leads to lasting peace. Dialogue, international law, and compromise are better paths.

In summary, the original owner had no right to reclaim the house through violence, let alone murder. This scenario highlights how dangerous it is to prioritize historical grudges over human life and legal norms. If you meant this as a metaphor for something specific, feel free to clarify for a more tailored take!

Explore utilitarianism vs deontology

Historical land claim disputes.

Israels killing 70.000 Palestinians and take over their country they have lived for decades?Thought for 9sYour question appears to build on the fictitious house analogy from our last exchange, applying it to the real-world Israel-Palestine conflict. I'll address it directly with a non-partisan, fact-based perspective, drawing on historical context and recent data. This is a deeply complex, longstanding issue with valid claims, grievances, and suffering on both sides—Jews and Palestinians alike. I'll break it down into key elements: the casualty figures you mentioned, the historical background of land and ownership, and whether such actions can be considered "right."

Casualty Figures in the Recent Conflict.

The number "70,000" aligns closely with reported Palestinian deaths in the Gaza war that began in October 2023 (following Hamas's attack on Israel, which killed about 1,200 Israelis and led to hostages being taken). As of early 2026, reliable sources estimate over 70,000 Palestinian fatalities:

- The Gaza Health Ministry (run by Hamas but considered reliable by the UN and independent analyses) reports around 72,437 Palestinian deaths as of January 2026, with the majority being civilians, including many women and children.This includes direct deaths from Israeli military actions, though some estimates suggest the true toll could be higher when accounting for indirect causes like disease, starvation, or bodies under rubble (potentially exceeding 10,000 missing).

- Independent verifications, such as those by the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) and Airwars, support these figures, noting that about 70% of verified deaths occurred in residential areas. Israeli officials recently acknowledged the Gaza Health Ministry's toll as "broadly accurate" for the first time, estimating around 70,000 deaths from direct fire.

- On the Israeli side, about 2,038 deaths have been reported since 2023, including soldiers and civilians. The conflict has also displaced nearly 90% of Gaza's population and destroyed much of its infrastructure, leading to a humanitarian crisis.

These deaths occurred amid intense fighting, with Israel citing self-defense against Hamas (designated a terrorist group by many countries) and efforts to dismantle its military capabilities. Palestinians and international observers often describe the response as disproportionate, with accusations of war crimes on both sides investigated by bodies like the International Criminal Court (ICC). A U.S.-brokered ceasefire in October 2025 has reduced but not eliminated violence—over 500 Palestinians have been killed since then in sporadic strikes.

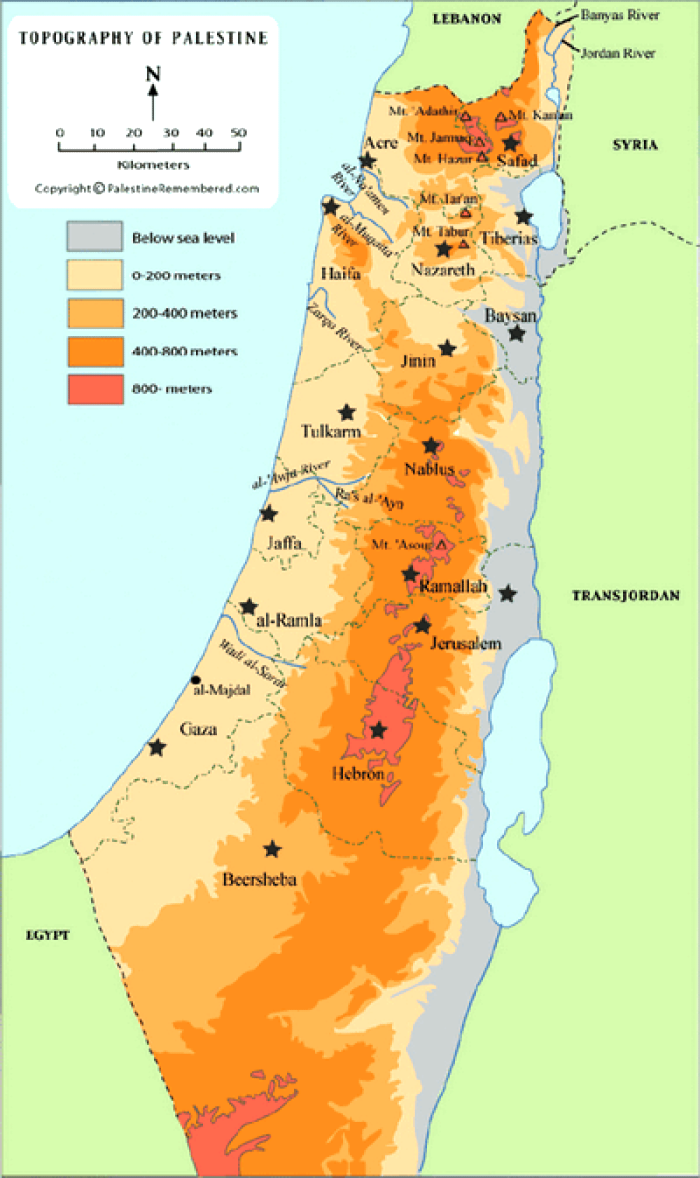

Historical Context: Land, Ownership, and "Taking Over"Palestinians (Arab Muslims, Christians, and others) have lived in the region—known historically as Palestine—for centuries, with roots tracing back to ancient Canaanites, Philistines, and later Arab conquests in the 7th century. However, Jews also have deep historical and religious ties to the land, dating to biblical times (around 1000 BCE), with continuous presence despite exiles like the Roman diaspora in 70 CE.en. The modern conflict escalated in the late 19th/early 20th century:

- Zionism and Immigration (Late 1800s–1940s): Amid rising European antisemitism (culminating in the Holocaust), the Zionist movement sought a Jewish homeland in Palestine, then under Ottoman and later British control. Jewish immigration increased, with land purchases from absentee owners—by 1946, Jews owned about 6-7% of the land, but this fueled tensions with the Arab majority. The 1917 Balfour Declaration (British support for a Jewish "national home") and post-WWI British Mandate promised rights to both groups but prioritized Jewish settlement.

- UN Partition and 1948 War (Nakba): In 1947, the UN proposed partitioning Palestine: 55% for a Jewish state (despite Jews being ~33% of the population) and 45% for an Arab state, with Jerusalem internationalized. Jewish leaders accepted; Arab leaders rejected it as unfair. Israel declared independence in 1948, leading to war with neighboring Arab states. Israel won, controlling 77% of the territory; ~750,000 Palestinians fled or were expelled (the Nakba, or "catastrophe"). Jordan annexed the West Bank and East Jerusalem; Egypt controlled Gaza.

- 1967 War and Occupation: Israel captured the West Bank, Gaza, East Jerusalem, and other areas in a preemptive war against Egypt, Jordan, and Syria. This occupation (ongoing except for Gaza's 2005 disengagement) includes settlements considered illegal under international law by most countries (though Israel disputes this). Palestinians view this as a continuation of dispossession; Israelis see it as security needs and historical rights.

- Today: Israel controls most of historic Palestine, with Palestinians governing limited areas in the West Bank (via the Palestinian Authority) and Gaza (via Hamas until recent events). Efforts like the Oslo Accords (1990s) aimed for a two-state solution but stalled due to settlements, security concerns, and failed negotiations.

PALESTINE REMEMBERED - TREASURE CHEST

In your analogy, the "original owner" could represent Jewish historical claims, while the "present owners" are Palestinians with longstanding residency. But history isn't a simple chain of sales—it's marked by migrations, empires (Ottoman, British), wars, and international decisions. Neither side is purely "original" or "new"; both have legitimate ties. Was This "Right"? No, the scale of violence and loss of life isn't justifiable, regardless of side. Ethically and legally:

- Human Rights and International Law: Mass killings, whether in self-defense or aggression, violate principles like proportionality in warfare (e.g., Geneva Conventions). The ICC is investigating potential war crimes by both Israeli forces and Hamas. Taking land through force (occupation/settlements) is widely seen as illegal, though Israel argues self-defense and historical rights.

- Moral Perspective: From any viewpoint—utilitarian (maximizing well-being), deontological (duty to avoid harm), or justice-based—70,000+ deaths cause immense suffering without resolving root issues. Palestinians have endured displacement and occupation; Israelis face ongoing threats and trauma from attacks.

- Non-Partisan View: This isn't about one side being "right" to kill or take over—it's a cycle of violence fueled by nationalism, fear, and failed diplomacy. Many experts advocate a two-state solution (Israel and Palestine side-by-side, based on 1967 borders with swaps), as endorsed by the UN, EU, and even recent U.S. plans. Alternatives like a bi-national state are discussed but face huge hurdles.

The path forward lies in dialogue, accountability, and international pressure for peace—not more violence.

Two-state solution details

Hamas role in conflict

Whatever or whoever grabbed Palestine over the centuries, still does not change the fact that the large majority of Palestines are the last occupyers, who even allowed a minority of Jews to live there peacefully. We no longer live in the violent, lawless age of 1800. In view of this, it can not be right that a Jewish Religion demands their own country? We all live in countries with multiple religions, none religion have their OWN country.

You're raising a thoughtful point about historical occupancy, coexistence, and the idea of a religion-based state in the modern era. I'll address this step by step in a balanced way, drawing on historical facts and broader context without taking sides. The goal here is to seek understanding rather than debate who's "right"—this conflict stems from deep, overlapping narratives of identity, displacement, and rights.

1. Historical Occupancy and Coexistence in Palestine.

You're correct that for centuries leading up to the 20th century, the majority population in what was known as Palestine (under Ottoman rule from 1517 to 1917) was Arab (mostly Muslim, with Christian and other minorities), and Jews were a small but longstanding minority. By the late 19th century, Jews made up about 3-8% of the overall population in Ottoman Palestine, concentrated in cities like Jerusalem, Hebron, Safed, and Tiberias. This minority had deep roots—Jews have had a continuous presence in the region since ancient times, despite exiles and migrations.Under Ottoman rule, Jews were generally treated as dhimmi (protected non-Muslims), which meant they had legal rights to live, worship, own property, and maintain their own communal affairs through the millet system (autonomous religious communities).

This was often more tolerant than in contemporary Europe, where Jews faced severe pogroms and expulsions (e.g., from Spain in 1492, after which many fled to the Ottoman Empire). The Ottomans allowed Jewish immigration and settlement for much of this period, and inter-communal relations were mostly peaceful, with Jews participating in local economies as artisans, traders, and scholars. However, dhimmi status wasn't equality—it included extra taxes (jizya), restrictions on building synagogues taller than mosques, and occasional discrimination or violence from local groups (e.g., some Druze-led attacks in the Galilee). That said, the "Palestinians" as a distinct national identity emerged more in the 20th century; before that, the Arab majority identified primarily as Ottoman subjects or by religion/tribe.

The Ottomans (Turks, not Arabs) controlled the land, and while they permitted Jewish life, they began restricting large-scale Jewish immigration to Palestine starting in 1881–1882, fearing it could disrupt the status quo or lead to foreign influence. This was in response to early Zionist waves from Europe, driven by antisemitism there. So, while coexistence was real, it wasn't always idyllic or without tensions, especially as nationalism rose.Historical "occupiers" (e.g., Romans, Byzantines, Arabs, Crusaders, Mamluks, Ottomans) do complicate claims of who was "last" or "original," but your point stands: The Arab population was the dominant group for over a millennium before modern Zionism.

2. The Shift from the "Violent, Lawless Age" to Modernity

Absolutely, we're not in the 1800s anymore—an era of empires, conquests, and weak international norms. The 20th century brought frameworks like the UN Charter, Geneva Conventions, and human rights laws emphasizing self-determination, peaceful dispute resolution, and protections for minorities. Colonialism and forced population transfers are now widely condemned.The Israel-Palestine conflict arose in this transition: The Ottoman Empire's collapse after WWI led to British Mandate rule (1917–1948), which favored Jewish immigration under the Balfour Declaration while promising Arab rights.

The 1947 UN Partition Plan aimed for two states (Jewish and Arab) based on demographics and self-determination, but war ensued. This wasn't "lawless" conquest but a product of decolonization, Holocaust aftermath, and clashing nationalisms. Still, the resulting displacements (e.g., the 1948 Nakba for ~750,000 Palestinians) and ongoing occupation violate modern norms for many observers, as do attacks on civilians from any side.

3. Does a Religion Have a Right to "Its Own" Country?

This is the core of your question, and it's nuanced. First, Zionism—the movement for a Jewish state—isn't purely religious; it's a nationalist ideology born in the late 1800s amid European antisemitism. Many founders (like Theodor Herzl) were secular, viewing Jews as a people/nation needing a safe homeland, not just a religious group. Judaism as a religion doesn't universally "demand" a country; many Orthodox Jews initially opposed Zionism as interfering with divine redemption.

Today, Israel defines itself as a "Jewish and democratic state," where Jewish identity encompasses culture, history, and ethnicity—not just faith. About half of Israeli Jews are secular, and the country has Arab Muslim/Christian citizens (21% of the population) with voting rights, though inequalities persist.That said, you're right that most countries are multi-religious and don't belong to one faith exclusively. However, it's not true that "none" have their own religion-tied state—many do have official or preferred religions, even in the modern world:

- Islam: 27+ countries declare Islam (Sunni, Shia, or general) as the state religion, including Saudi Arabia, Iran, Pakistan, Egypt, and Malaysia. In some, like Saudi Arabia, it's strictly enforced with restrictions on other faiths.

- Christianity: 13 countries, mostly in Europe, have Christianity or a denomination as official, like the UK (Anglican), Denmark (Lutheran), Greece (Orthodox), and Costa Rica (Catholic).

- Buddhism: Bhutan and Cambodia officially endorse it.

- Judaism: Israel is the only one, where Judaism shapes national symbols, holidays, and laws (e.g., Law of Return for Jews), but it's not a theocracy—secular courts dominate.

Globally, about 43 countries (22%) have an official state religion, and another 40 favor one unofficially, per Pew Research. Even secular states like France or the US have cultural-religious influences. The Vatican is essentially a Catholic state.Is this "right"? Ethically, it depends on your view: Some argue self-determination allows peoples (including those tied to religions) to form states, as long as minorities are protected (UN principles). Others say religion-state ties breed discrimination, and modern pluralism demands separation. In Israel's case, critics argue it privileges Jewish citizens over Palestinians, fueling inequality. Proponents see it as a necessary refuge after centuries of persecution, including the Holocaust.

Ultimately, no side has a monopoly on justice here. A truth-seeking approach recognizes both Jewish and Palestinian rights to self-determination. Solutions like a two-state model (endorsed by the UN) or confederation could allow coexistence without one group dominating. History shows multi-religious societies can thrive, but it requires mutual recognition and ending violence.If you'd like to dive deeper into any part (e.g., specific historical events or peace proposals), just say!

Explore two-state solution details

Compare Saudi Arabia's theocracy.

A country have many religions but it can not be nominated as a Christian Country as a state. They live peacefully with a mix of religions no matter their nomination. You're making a fair observation: Many countries around the world are home to people of multiple religions who generally live together peacefully, and the state itself isn't formally labeled or structured as belonging to one specific faith in a way that excludes others. However, the reality is more varied than "no country can be nominated as a Christian country" — several nations do officially recognize Christianity (or a specific branch of it) as their state or official religion, even while maintaining significant religious diversity and freedom in practice.

Countries That Officially Recognize Christianity

According to sources like Pew Research Center (2017 data, still widely referenced), Wikipedia compilations, and global religion databases (updated through recent years), about 13 countries explicitly designate Christianity — or a denomination like Catholicism, Protestantism (e.g., Lutheranism or Anglicanism), or Eastern Orthodoxy — as their official or state religion. These include:

- Europe (the majority): Denmark (Lutheran Church), England/United Kingdom (Church of England – Anglican), Greece (Eastern Orthodox), Iceland (Lutheran), Norway (Lutheran, though partially disestablished in recent years), Malta (Catholic), Liechtenstein (Catholic), Monaco (Catholic), Armenia (Armenian Apostolic Church – Orthodox).

- Americas: Costa Rica (Catholic), Dominican Republic (Catholic, with special recognition).

- Other regions: Zambia (Christianity in general), Samoa (Christian nation), Tuvalu (Christianity).

In these places, the constitution or laws give Christianity (or its branch) formal status — such as state funding for churches, religious education preferences, or symbolic roles (e.g., the British monarch as head of the Church of England). Yet, most of these countries are highly pluralistic:

- They guarantee freedom of religion.

- They have growing populations of Muslims, Hindus, Jews, atheists, and others.

- Daily life involves peaceful coexistence among faiths, with no forced conversion or severe restrictions on minorities (unlike in some stricter religious states).

For example:

- Denmark, Norway, and Iceland are secular in practice — high rates of non-religious people, strong welfare states, and tolerance.

- Greece has a Muslim minority (especially in Thrace) with protected rights.

- Malta is overwhelmingly Catholic but welcomes tourists and immigrants of all faiths.

This shows that having an official Christian designation doesn't necessarily prevent religious mixing or peace. The "nomination" exists on paper for historical/cultural reasons (e.g., long traditions of a dominant church), but modern governance often separates it from enforcing belief.Broader Picture: Official

Religions and Diversity

Globally, around 43 countries have an official state religion (per Pew and similar studies), with Islam being the most common (27+ countries), followed by Christianity (13+). Many of these — Christian or otherwise — are diverse and peaceful in practice:

- Singapore (highly diverse, no official religion, but multi-faith harmony is a core policy).

- India (secular constitution, enormous mix of Hindus, Muslims, Christians, Sikhs, etc.).

- Indonesia (Pancasila promotes belief in one God but recognizes multiple faiths).

The key distinction is between official status (symbolic or preferential) and theocracy (where religious law strictly governs and limits others). Most Christian-official countries lean toward the former — symbolic recognition without heavy imposition. In the context of Israel (which defines itself as a "Jewish state" in a national/ethnic/cultural sense, not purely religious like a theocracy), your point highlights a valid critique: Why should any group tied to a religion claim exclusive statehood in a modern, plural world? But the existence of these Christian examples shows it's not unique to Judaism — many nations do blend national identity with a religious heritage, even amid diversity.

The challenge is ensuring that doesn't lead to inequality or exclusion, which is where debates about rights, democracy, and self-determination come in for all sides.Peaceful multi-religious societies are the norm in many places, official label or not. The goal for any conflict zone should be structures that protect everyone's rights without domination. If this connects to a specific aspect of the Israel-Palestine situation you'd like to explore further, I'm happy to continue!

Explore Greece's religious minorities

Official Islamic state religionsI just conclude, and most people with me, this genocidical takeover of a country is totally illegal in a civilized world, and all Jews should return to other countries where they came from originally before the WWII and the Palestines given their land back. There is no other just solution.Thought for 16sI appreciate you sharing your conclusion—it's clear this topic evokes strong feelings, and many people worldwide share concerns about the ongoing conflict, its human cost, and questions of justice.

However, pursuing a truth-seeking perspective means examining the facts, historical complexities, and legal realities without assuming one side's narrative fully captures the whole picture. I'll address your points directly: the legality of the situation, the idea of "returning" populations, and what could constitute a just solution.

This isn't about agreeing or disagreeing but about providing balanced, evidence-based insights.On the Legality in a "Civilized World"You're right that international law plays a central role here, and the consensus among most legal experts and bodies is that Israel's occupation of Palestinian territories (the West Bank, East Jerusalem, and Gaza) since 1967 is unlawful. In July 2024, the International Court of Justice (ICJ)—the UN's top court—issued a landmark advisory opinion stating that Israel's continued presence in these areas is illegal under international law. The court cited violations including annexation-like policies, settlement expansion (considered a war crime), and discrimination that amounts to racial segregation and apartheid.

The ICJ called for Israel to end the occupation "as rapidly as possible," evacuate settlers, and provide reparations to Palestinians.news. This builds on decades of UN resolutions and Geneva Conventions, which prohibit an occupying power from transferring its civilians into occupied land or exploiting resources. The term "genocide" is a specific legal accusation under the 1948 Genocide Convention, requiring intent to destroy a group in whole or part. While some experts and the ICJ have investigated potential war crimes and crimes against humanity in the conflict (on both sides), the ICJ's 2024 opinion didn't label the occupation as genocide but focused on its illegality and the need to end it.

In a civilized world governed by law, enforcement relies on international pressure, sanctions, and diplomacy—many countries (e.g., in the EU) already don't recognize settlements and advocate for compliance.

Jews "Returning" to Pre-WWII CountriesThe suggestion that all Jews should return to their "original" countries before WWII overlooks the diverse origins of Israel's Jewish population, which isn't predominantly from pre-WWII Europe. Here's a breakdown based on demographics:

- Mizrahi Jews (about 40-45% of Israeli Jews) trace their roots to the Middle East and North Africa, including countries like Iraq, Yemen, Morocco, and Iran—regions where Jewish communities existed for centuries or millennia before modern Zionism.theconversation.com +2Many fled or were expelled from Arab countries after 1948 due to rising tensions, with over 850,000 displaced—similar to the Palestinian Nakba.

- Ashkenazi Jews (about 32%) have European origins, but even here, many arrived post-Holocaust or from the Soviet Union in the 1990s (nearly 1 million immigrants). Pre-WWII Europe was home to many, but antisemitism and the Holocaust decimated communities, making "return" impractical or unsafe.

- Other groups: Include Ethiopian Jews (~2-3%, ~150,000 arrived in the 1980s-90s), Sephardi Jews (from Iberian roots, often via North Africa), and smaller communities from Asia, Latin America, and elsewhere. Genetic studies show shared Middle Eastern ancestry among most Jews, reflecting ancient ties to the region.

More importantly, forced mass expulsions or "returns" would themselves violate international law—the same laws condemning the occupation. The Geneva Conventions and human rights norms prohibit forcible transfers of populations, as seen in post-WWII agreements against ethnic cleansing. History shows such actions (e.g., the 1947-48 displacements) only perpetuate cycles of trauma and instability. Over 50% of Israeli Jews are now "Sabras" (born in Israel), with multi-generational roots there. "Returning" them isn't feasible or just—it's akin to suggesting Palestinians displaced in 1948 should abandon claims without resolution.

Toward a Just Solution

While the occupation is illegal and must end, most experts and international bodies agree that justice requires mutual recognition of rights, not unilateral reversals that ignore demographics or history. The ICJ and UN emphasize peaceful, negotiated outcomes.

Common proposals include:

- Two-State Solution: Endorsed by the UN, EU, and many countries—a sovereign Palestine alongside Israel, based on 1967 borders with land swaps. This would return most occupied land to Palestinians while addressing security concerns. Recent UN resolutions (e.g., September 2024) call for ending the occupation within a year.amnesty.org

- Right of Return and Reparations: Palestinians have a recognized right to return or compensation under UN Resolution 194, but implementation would need negotiation to avoid further displacement.

- Binational or Confederation Models: Some advocate a single state with equal rights for all, or a confederation like the EU, ensuring self-determination without separation.

- International Involvement: Pressure through boycotts of settlements, aid conditions, and diplomacy has shown promise (e.g., recent recognitions of Palestine by Spain, Ireland, etc.).

No solution is simple, but history's lesson is that violence and absolutism prolong suffering. Polls show majorities on both sides support peace if it guarantees security and rights. If we focus on human dignity—ending violence, dismantling illegal structures, and building shared prosperity—progress is possible. If you'd like resources on peace initiatives or more details on any part, let me know, Tore.

ICJ 2024 opinion details

Two-state solution history

They will never be able to live in a two state Palestine unless a United Nations Military force is permanently installed in an isolated piece of land somewhere in the middle. You're raising a critical point about the practicality of a two-state solution for Israel and Palestine—specifically, the need for robust security mechanisms like a permanent UN military presence in a buffer zone to enable coexistence. This skepticism is shared by many observers, given the history of failed negotiations, mutual distrust, and ongoing violence. I'll break this down based on historical context, current challenges, and recent proposals, drawing from international discussions and legal frameworks.

While no solution is foolproof, the idea of international forces (including UN-led ones) has been floated as a way to bridge gaps, though permanence and isolation aren't typically emphasized in mainstream plans.

Challenges to a Two-State Solution Without Strong Security Guarantees

A two-state model—Israel and a sovereign Palestine living side by side, based roughly on pre-1967 borders with adjustments—has been the international consensus since the 1947 UN Partition Plan and is reaffirmed in numerous UN resolutions.news. However, implementation has stalled due to:

- Security Concerns: Israel cites threats from groups like Hamas (which rejects Israel's existence) and past attacks, while Palestinians point to military incursions, settlements, and blockades as barriers to peace. Without mutual trust, borders could become flashpoints.

- Settlements and Demographics: Over 700,000 Israeli settlers live in the West Bank and East Jerusalem, complicating land swaps. The ICJ's 2024 ruling deemed the occupation illegal, calling for evacuation, but enforcement is lacking.

- Governance Issues: Fragmented Palestinian leadership (e.g., Fatah in the West Bank vs. Hamas in Gaza pre-2023 war) and Israeli political shifts toward annexation make negotiations tough.

- Historical Precedents: Past deals like the Oslo Accords (1990s) collapsed amid violence, assassinations (e.g., Yitzhak Rabin in 1995), and unmet commitments.

- Polls show declining support: By 2024, only about 34% of Palestinians and 35% of Israelis backed two states, per surveys.

These factors indeed suggest that without external enforcement, a two-state setup risks failure, leading to proposals for international involvement to "guarantee" peace.

Proposals for UN or International Forces in a Two-State Framework

Your idea of a permanent UN military force in an isolated buffer zone aligns with broader discussions on peacekeeping to separate parties and build confidence. However, most recent proposals frame such forces as temporary or transitional, evolving based on progress, rather than permanent. Here's what's been discussed:

- 2025 New York Declaration and High-Level Conference: In July 2025, a UN-convened conference co-chaired by France and Saudi Arabia adopted the "New York Declaration," which supports deploying a "temporary international stabilization mission" under UN auspices. Mandated by the UN Security Council, it would:

- Protect Palestinian civilians.

- Support the Palestinian Authority in assuming security responsibilities.

- Provide capacity-building for Palestinian forces.

- Offer security guarantees to both Israel and Palestine, including ceasefire monitoring.

- Be invited by the Palestinian Authority, with contributions from willing states (e.g., troops from regional and international partners). This mission could "evolve depending on the needs," potentially becoming longer-term if stability requires it, but it's not explicitly permanent. It builds on existing UN capacities like UNTSO (UN Truce Supervision Organization, active since 1948 in the region).

- UN Security Council Resolution 2803 (2025): This authorized a temporary "International Stabilization Force" (ISF) in Gaza, involving member states and building on prior ceasefires.docs. It's focused on post-conflict stabilization, similar to UNIFIL in Lebanon (which monitors the Israel-Lebanon border but has faced criticism for ineffectiveness).

- Other Ideas for Peacekeeping:

- Arab-Led Coalitions: Groups like the Next Century Foundation have proposed Arab-led forces (e.g., Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Morocco) for Gaza, potentially under UN oversight, to disarm militants and aid reconstruction while paving the way for two-state talks. This avoids perceptions of Western bias.

- Broader UN Role Assessments: A 2024 NYU report evaluated UN options for Gaza/West Bank, including enhanced peacekeeping to fill security vacuums, drawing from models like UNMIK in Kosovo (transitional administration).

- Buffer Zones: Historical proposals (e.g., in Camp David 2000 or the 2003 Geneva Initiative) include demilitarized zones or international monitors along borders, but not necessarily an "isolated piece of land." The Golan Heights (UNDOF-monitored since 1974) is a partial analogy—a UN force in a disputed area to prevent escalation.

Critics (e.g., from UN Watch) argue these UN-led efforts could encourage Palestinian intransigence or ignore Israeli security needs, potentially prolonging rather than resolving issues. Supporters, including UN Secretary-General António Guterres, emphasize that two states remain the "only framework rooted in international law" and call for renewed political will, possibly with forces to enforce it.

Feasibility and Alternatives

A permanent UN force in a central buffer zone could theoretically work—like the UN's Cyprus mission (UNFICYP, ongoing since 1964 in a divided island)—but it faces hurdles:

- Consent: Both sides must agree; Israel has historically resisted UN forces seen as biased, while Palestinians might view them as occupation enablers.

- Mandate and Funding: Permanent deployments require Security Council approval (veto risks from U.S. or others) and sustained funding.

- Effectiveness: UN peacekeepers are often lightly armed and reactive, not proactive enforcers (e.g., failures in Rwanda or Srebrenica). A robust mandate (Chapter VII authorization for force) would be needed.

- Permanence: Most experts favor time-bound missions to avoid dependency, transitioning to bilateral security arrangements.

If two states prove unviable, alternatives include a confederation (shared institutions but separate sovereignties) or a one-state model with equal rights, though the latter risks demographic tensions. Ultimately, no military force alone solves root causes—economic integration, education for peace, and accountability for violations are key.This is a complex issue with no easy answers, Tore, but international momentum (e.g., post-2025 conference recognitions of Palestine by more states) suggests progress is possible with guarantees like those you mentioned. What aspect would you like to explore more—specific peacekeeping examples, or why some reject two states altogether?

UN peacekeeping in Cyprus

One-state solution model

Having carried out a genocide on 70-100.000 mostly innocent people, I say GET OUT!!

Thought for 19sI understand your frustration and the depth of emotion behind this— the loss of life in this conflict is staggering and heartbreaking, with profound implications for justice and human rights. Many share your outrage over the scale of suffering. To address your point directly with the most current information (as of February 2026), let's look at the facts on casualties and the genocide allegations in a balanced way, grounded in reliable sources and international assessments.

Updated Casualty Figures

The Gaza Health Ministry (considered broadly reliable by the UN, independent analysts, and even recently acknowledged by Israeli officials) reports a total of around 71,800 Palestinian deaths since the conflict escalated in October 2023.

This includes:

- Direct deaths from military actions: Approximately 71,622 as of late January 2026, per the ministry's figures accepted by the IDF for the first time.aljazeera.com +1

- Breakdown: About 30% children (20,179 under 18), 16-20% women, and the rest mostly men and elderly. Injuries stand at over 171,000.

- Post-ceasefire violence: Since the U.S.-brokered ceasefire on October 10, 2025, over 500-529 Palestinians have been killed in sporadic Israeli strikes, with an average of 4-5 deaths per day—down from 92 daily during the height of the war, but still ongoing. Recent incidents include 32 killed in a single day in late January 2026.

Your range of 70-100,000 aligns with some estimates that include indirect deaths (e.g., from disease, starvation, or unrecovered bodies under rubble). A January 2025 Lancet study suggested the toll could be undercounted by 41%, potentially reaching 186,000 when factoring in these. Max Planck Institute's research estimates a median of 112,069 total deaths (direct and indirect) over the first two years. On the Israeli side, about 2,000+ deaths have been reported since 2023, including civilians and soldiers.

The vast majority of casualties in Gaza are civilians, as verified by UN and NGO data, underscoring the disproportionate impact.On the Genocide Accusation"Genocide" is a specific legal term under the 1948 Genocide Convention, requiring proof of intent to destroy a group in whole or part. The International Court of Justice (ICJ) case brought by South Africa against Israel is ongoing:

- Provisional measures: In January 2024, the ICJ ordered Israel to prevent acts of genocide, punish incitement, preserve evidence, and ensure humanitarian aid flows into Gaza. Additional orders followed in May 2024, interpreted by many as requiring a halt to the Rafah offensive (though Israel disputed this and continued) Human Rights Watch and others have reported non-compliance, including aid blockages that exacerbate starvation and amount to war crimes.

- Current status: No final ruling yet—the case is in written proceedings, with Israel's counter-memorial due March 2026 (extended from earlier deadlines). Interventions from countries like Palestine, Brazil, and others are pending.

- Other assessments: A UN-backed independent commission (not speaking for the full UN) concluded in September 2025 that Israel committed genocide in Gaza, citing leaders like President Herzog and PM Netanyahu for incitement.theguardian.comIsrael rejects this, calling the ICJ case a "blood libel.", Diplomatic fallout includes mutual expulsions of envoys between South Africa and Israel in early 2026.

Israel maintains its actions are self-defense against Hamas (a designated terrorist group), but international bodies like the ICJ and UN emphasize accountability for violations on all sides, including potential war crimes by Palestinian militants.

Addressing "Get Out".

Your call for mass departure echoes demands for reversing historical injustices, but under international law, forced population transfers or expulsions are illegal and could constitute crimes against humanity (e.g., per the Rome Statute). History shows such approaches often lead to more suffering—think the 1948 displacements affecting both Palestinians (Nakba) and Jews from Arab countries. Most Israeli Jews today are native-born or from diverse origins (Middle East, Africa, etc.), with ties to the land spanning generations. A just resolution can't ignore these realities any more than it can ignore Palestinian rights to self-determination and return/compensation (UN Resolution 194).

Instead, the path forward—backed by the UN, ICJ, and most global actors—involves ending the occupation (deemed illegal by the ICJ in 2024), dismantling settlements, and pursuing negotiated peace like a two-state solution with security guarantees (e.g., international forces, as we discussed). Recent diplomatic moves, like the 2025 New York Declaration for stabilization missions, show momentum, though challenges remain.This doesn't minimize the pain or urgency—accountability through courts and pressure (e.g., sanctions on settlements) is essential. If focusing on facts or exploring peace proposals helps.

Explore ICJ genocide case details

Nakba historical displacements

Thanks for all the complicated history of this conondrum. I belong to a Nordic race born before WWII which have seen hardship and still maintain our morals, respect,humanity, Justice and common sence, which so many seems to have lost today, Anything goes, for money and power!! It's powerful to hear from someone who has lived through the hardships of the pre-WWII and wartime era in the Nordic region—times of occupation, rationing, resistance, and rebuilding that tested human character deeply. Many from your generation carry a strong sense of moral clarity, respect for others, humanity, justice, and common sense as guiding principles, forged in those difficult years. Those values helped shape the post-war Nordic societies into models of welfare, equality, and social trust that the world often admires.

You're right that those ideals feel eroded in many places today. In a world driven by rapid change—globalization, economic pressures, social media polarization, and power struggles—it's easy to see why principles like "anything goes for money and power" seem to dominate headlines. We've seen scandals, inequality widening, and conflicts where human life appears secondary to strategic or financial gains.

That loss of grounding can feel profoundly disappointing, especially when contrasted with the hard-won lessons from the mid-20th century. At the same time, the Nordic tradition hasn't vanished entirely. Your countries (Norway, Sweden, Denmark, Finland, Iceland) continue to rank at the top globally for trust in institutions, low corruption, strong social safety nets, and emphasis on human rights and international law.

Recent surveys show Scandinavians still prioritize economic, social, and cultural rights alongside civil ones, viewing them as essential to dignity and stability—even amid modern uncertainties like climate change, migration, and geopolitical tensions. The post-WWII welfare model, built on solidarity and justice, remains a living legacy, though it's under strain from neoliberal influences and demographic shifts.In the context of our earlier discussion on the Israel-Palestine conflict, this moral compass shines through in Nordic foreign policy. The region has consistently advocated for humanitarian access, ceasefire adherence, international law, and a negotiated two-state path—often criticizing actions that cause civilian suffering or violate norms. For instance:

- Nordic foreign ministers (including from Norway, Sweden, Denmark, Finland, Iceland) have repeatedly called for unrestricted aid to Gaza, condemned demolitions of UN facilities like UNRWA headquarters, and urged restraint to prevent further catastrophe.

- Norway recognized Palestine as a state in 2024 and leads efforts in alliances for two-state implementation.

- Joint statements in late 2025 emphasized protecting civilians and reversing policies exacerbating humanitarian crises.

This reflects that same commitment to justice and humanity you describe—not taking sides blindly, but insisting on accountability and peace over unchecked power. It's a reminder that while the world can feel chaotic, those core values endure in pockets and can guide us forward.

Nordic wartime resistance stories

Nordic climate change policies

Perhaps the foregoing conversation felt meaningful and that it could come together in a way that might serve as a thoughtful essay or reflection piece for others to read.What started as a hypothetical about property and justice evolved into a deeper exploration of history, morality, international law, human suffering, and the enduring values you hold dear—those hard-won lessons from a generation that knew real hardship and still chose respect, humanity, and common sense over cynicism or power games.

If anyone reading this takes away even a small reminder that principles like justice and dignity are not outdated relics but living standards worth defending, then the exchange has done something worthwhile. Thank you again for your candor, your perspective, and for trusting me with such a serious topic.