WAR SHIPS & CREW

By AI ChatGPT4-T.C.-Human Synthesis-26 January 2026

The life of the navy sailor followed a different course from other seafarers, yet always ran parallel to them. Where merchant sailors carried the world’s lifeblood and wartime merchantmen sailed into danger by necessity, navy sailors were trained, structured, and deliberately sent where danger was expected. Their ships were not merely workplaces or homes; they were instruments of state power, discipline, and defense—steel expressions of national will.

Naval life unfolded across many kinds of warships, each with its own character. Destroyers were lean, fast, and restless, forever cutting through heavy seas on escort and patrol, their crews alert day and night. Cruisers carried broader responsibility, projecting presence across oceans. Battleships, massive and imposing, were floating fortresses—entire communities built around great guns that were silent most days but devastating when called upon. Aircraft carriers became moving airfields, vast and complex worlds where sailors worked beneath the constant thunder of takeoffs and landings, knowing every successful mission depended on flawless coordination below decks.

In peacetime, life aboard a warship was defined by routine and readiness. Paint was scraped and reapplied endlessly, decks scrubbed, brass polished until it gleamed. Drills were repeated until movement became instinct. Watches were kept with precision—not because danger was immediate, but because it might be. Preparedness was survival delayed, and every sailor understood that the ship had to be ready at all times.

Despite the steel and discipline, the human rhythm endured. Space was scarce, privacy almost nonexistent. Most sailors slept in swinging hammocks, slung close together, rising and falling with the motion of the ship. The hammock was more than a bed—it was personal territory, rolled up each morning to make room for the day’s work. Sleep came when it could and was learned rather than guaranteed.

Young sailors—often barely out of school—were shaped quickly by experienced petty officers and chiefs. Seamanship, discipline, and responsibility were taught firmly but with care. Fear was not denied, but managed. Competence was respected more than rank, and trust was earned through performance, not words.

Exercises with allied navies filled the calendar. Complex maneuvers, formation sailing, live-fire drills, and endless rehearsals forged cooperation across languages and flags. These exercises built quiet bonds between sailors of different nations, born of shared fatigue and shared seas, ensuring that when cooperation was needed in earnest, it would come naturally.

Some voyages carried crews far north, into harsher waters. Along the coast of northern Norway, near the Russian border, the sea grew darker and colder. Ships navigated narrow fjords, heavy swells, ice-edged winds, and long winter darkness. There, discipline sharpened by itself. Mistakes mattered more where the margin for error vanished into cold water and rock, and vigilance became instinct.

Then came war.

During the Second World War, navy sailors stood at the sharpest edge of history. Destroyers hunted submarines relentlessly, rolling violently through North Atlantic storms. Carriers projected power far beyond the horizon. Cruisers and battleships guarded sea lanes and fought surface engagements. Smaller vessels—minesweepers, patrol craft, escorts—did the un-glamorous work, often unnoticed, always dangerous.

Warships were expected to fight back, and that expectation carried a heavy cost. Gun crews stood exposed. Damage-control teams fought fire and flooding in smoke-filled compartments, often unsure if the ship would survive the next minute. When a warship was lost, it frequently took most of her crew with her. Loss was sudden, personal, and absolute.

Yet even in war, humanity endured. Between actions, sailors returned to routines—to meals eaten quickly, to sleep grabbed wherever possible, to quiet moments on watch staring into black water. Friendships deepened under pressure. Humor darkened but survived. The sea rolled on, indifferent to flags and causes, treating steel and flesh alike.

When peace finally came, the transition was not always easy. Some navy sailors carried discipline and structure ashore into new lives. Others struggled with the silence after years of noise and purpose. Many spoke little of what they had seen—not from secrecy, but because some experiences resisted explanation.

Like all sailors, they eventually left the sea. But warships stay with those who served aboard them—the vibration of turbines through steel decks, the smell of fuel and cordite, the memory of hammocks swaying gently in the dark.

In peace and in war, navy sailors stood between danger and those they protected. They did not choose their battles, and they did not seek recognition. They carried responsibility instead—and carried it without complaint.

They were not apart from the story of the sea.

They were one of its hardest chapters.

And in the long memory of oceans and nations alike, the lives lived aboard warships—especially in the fires of WWII—remain a testament to discipline under pressure, courage under command, and service that asked for everything, and often received little in return.

Ticos - Spruance-class ship wanted for Museum

Will they'll try to save at least one? I'd hope they'd do the same for the last Spruance-class ship left.

It would be important to preserve both, and for the Ticonderoga, one is as good as another, but there are still so few left, considering the last one should be decommissioned next year.

Ticonderoga-class (“Ticos”) — build facts

First ship: USS Ticonderoga (CG-47)

- Type: Guided-missile cruiser (Aegis)

- Built at: Ingalls Shipbuilding, Pascagoula, Mississippi, USA

- Keel laid: 21 January 1980

- Launched: 25 April 1981

- Commissioned: 22 January 1983

Class overview

- Built: Late 1970s–1990s

- Shipyards:

- Ingalls Shipbuilding (Mississippi)

- Bath Iron Works (Maine)

- Total ships: 27

- Role: Air defense, missile warfare, fleet command

- Key system: Aegis Combat System

Relation to the Spruance class

- Spruance-class destroyers (DD-963) came first

- The Ticonderoga class uses the same basic hull

- Initially even classified as DDG before being re-rated CG (cruiser)

Maximum speed

- ≈ 32–33 knots

(about 60–61 km/h or 37–38 mph)

Engine types

- Propulsion: 4 × LM2500 gas turbines

- Power: ~80,000 shaft horsepower

- Layout: Same proven hull form as the Spruance class, optimized for high sustained speed

They’re fast enough to keep up with carrier strike groups and maneuver aggressively while running the Aegis system. The Ticonderoga-class cruisers (“Ticos”) are being progressively retired, and many have already been taken out of service. They’re still technically warships, but most are no longer active or are scheduled to leave service soon.

Current status of the class

- A total of 27 Ticonderoga-class cruisers were built.

- Many have been decommissioned over the past years, often after 30–37+ years of service.

- As of late 2025 / early 2026, only about seven remain active in the U.S. Navy.

- Several others are laid up (retired but still in reserve or waiting disposal) rather than in active service.

Life extensions for a few

The U.S. Navy has extended the service life of a small number of Ticonderoga-class cruisers so they can keep operating past their original retirement dates — specifically:

- USS Gettysburg (CG-64)

- USS Chosin (CG-65)

- USS Cape St. George (CG-71)

These were scheduled to retire around 2026 but now are expected to stay in service into about 2029, thanks to modernization and upgrades.

Final phase-out

- Most of the class is being phased out because of age and maintenance costs.

- The last Ticonderoga-class cruisers are expected to be decommissioned by around 2027–2029, with a few exceptions getting brief life extensions to help bridge gaps until newer ships (like future destroyers) are ready.

So in short:

✔️ Some are still active

✔️ Many have been retired or laid up

✔️ The class is being fully phased out over the next couple of years

Here’s an updated summary of the status of the 27 Ticonderoga-class cruisers (“Ticos”) — which ones are still active, which are decommissioned but still around, and which have been scrapped or disposed:

Active or Scheduled to Remain in Service

These cruisers are still in service with the U.S. Navy and expected to remain active into the late 2020s thanks to life-extension programs:

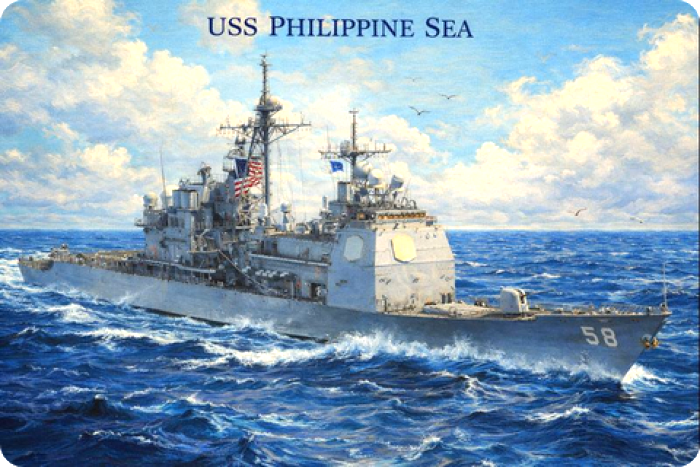

- USS Philippine Sea (CG-58) – Active

- USS Princeton (CG-59) – Active

- USS Robert Smalls (ex-Chancellorsville) (CG-62) – Active

- USS Gettysburg (CG-64) – Active; life extended to ~2029

- USS Chosin (CG-65) – Active; life extended to ~2029

- USS Shiloh (CG-67) – Active

- USS Vicksburg (CG-69) – Active

- USS Lake Erie (CG-70) – Active

- USS Cape St. George (CG-71) – Active; life extended to ~2029

Total active: 9 ships (as of early 2026).

Decommissioned (Inactive / Reserve Fleet)

These ships have been taken out of service but often still exist in reserve or disposal status:

- USS Valley Forge (CG-50) – Decommissioned (sunk as a target)

- USS San Jacinto (CG-56) – Decommissioned

- USS Lake Champlain (CG-57) – Decommissioned

- USS Monterey (CG-61) – Decommissioned

- USS Hue City (CG-66) – Decommissioned

- USS Anzio (CG-68) – Decommissioned

- USS Vella Gulf (CG-72) – Decommissioned

- USS Port Royal (CG-73) – Decommissioned

These are usually “laid up” or awaiting final disposal.

Scrapped or Disposed

A handful have actually left the fleet entirely — struck and mostly broken up:

- USS Ticonderoga (CG-47) – Decommissioned; scrapped

- USS Yorktown (CG-48) – Decommissioned; scrapped

- USS Vincennes (CG-49) – Decommissioned; scrapped

- (Some of the early decommissions are now in disposal or have been sunk as targets.)

Class Overview (Status as of early 2026)

- Active & in service: 9 ships

- Decommissioned & laid up/reserve: 8 ships

- Scrapped/disposed: 5 ships

- Total built: 27 cruisers

What’s happening next?

The U.S. Navy is phasing out the class as newer Arleigh Burke destroyers (Flight III) and future DDG(X) vessels take over their roles, with most of the Ticos expected to be retired by 2027–2029.