MERCOSUR & BRICS

By AI ChatGPT4-T.Chr.-Human Synthesis-09 January 2026

Does Mercosul have any connection with BRICS?

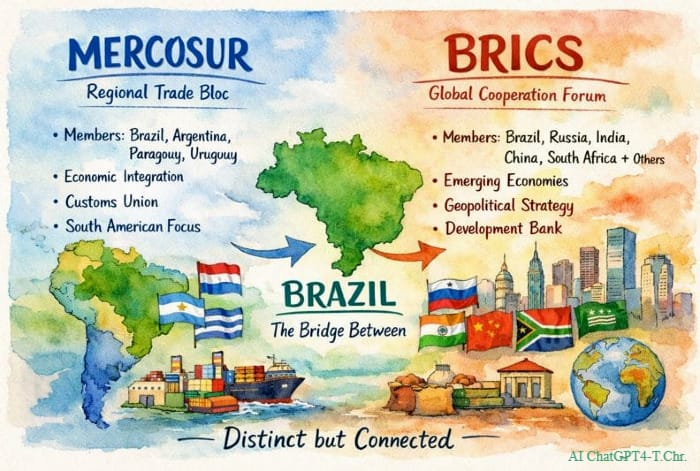

No formal institutional connection — but there is overlap and increasing strategic interaction.

1. What Mercosur is

Mercosur (Mercosul) is a regional trade bloc focused on economic integration in South America.

Members (as of now):

- Brazil

- Argentina

- Paraguay

- Uruguay

- (Bolivia is in the process of full accession)

Purpose:

- Customs union / trade facilitation

- Common external tariff

- Regional economic coordination

It is regional, trade-focused, and legally structured through treaties.

2. What BRICS is

BRICS is a geopolitical and economic cooperation forum among major emerging economies.

Members (after expansion):

- Brazil

- Russia

- India

- China

- South Africa

- new members (e.g., Saudi Arabia, UAE, Iran, Ethiopia, Egypt, etc.)

Purpose:

- Strategic coordination

- Financial cooperation (e.g., New Development Bank)

- Reform of global governance institutions

- South–South cooperation

It is global, non-regional, and not a trade bloc.

3. The overlap: Brazil

The key link is Brazil:

- Brazil is a founding member of Mercosur

- Brazil is also a founding member of BRICS

Because Brazil is the largest economy in South America, it often:

- Channels BRICS-related initiatives into regional discussions

- Promotes South American interests within BRICS

- Encourages multipolar financial alternatives that may indirectly benefit Mercosur countries

But this is political influence, not institutional linkage.

4. No formal coordination mechanism

There is:

- ❌ No joint secretariat

- ❌ No shared treaty framework

- ❌ No automatic policy alignment

- ❌ No Mercosur–BRICS agreement

Any interaction happens through:

- Bilateral diplomacy

- Brazil’s foreign policy priorities

- Occasional dialogue in multilateral settings

5. Indirect connections (important nuance)

Although there is no formal link, BRICS initiatives can affect Mercosur countries indirectly, for example:

- New Development Bank (NDB) lending to infrastructure projects in Brazil that affect regional trade

- Trade settlement in local currencies promoted by BRICS influencing Brazil–Argentina arrangements

- Geopolitical alignment around multipolarity influencing Mercosur’s external trade posture

These are spillover effects, not structural ties.

6. Bottom line

- Mercosur ≠ BRICS

- They operate at different levels (regional trade vs. global strategic coordination)

- Brazil is the bridge, but the bridge is political, not legal

If Brazil is the major creator of Mercosur and Brics, who actually invented/started it?

Brazil was central, but it did not invent either Mercosur or BRICS alone. Both were collective creations, born from specific historical moments, with identifiable initiators.

Below is the precise origin story of each.

1. Who started Mercosur

Mercosur was co-created by Brazil and Argentina, not by Brazil acting alone.

Key facts

- Political architects:

- José Sarney (Brazil)

- Raúl Alfonsín (Argentina)

- Trigger moment:

- The Iguaçu Declaration (1985) — Brazil and Argentina agreed to end rivalry and pursue economic integration after military rule.

- Formal founding:

- Treaty of Asunción (1991)

- Original members: Brazil, Argentina, Paraguay, Uruguay

Why it happened

- Reduce historic Brazil–Argentina rivalry

- Lock in democratic transitions

- Create a South American bargaining bloc

- Prevent external dominance (US/EU) in trade terms

Mercosur was a bilateral reconciliation project that expanded, not a Brazilian imposition.

2. Who started BRICS

BRICS began outside governments, then was adopted by states.

Step-by-step origin

- 2001 – The term “BRIC” was coined by Jim O’Neill, chief economist at Goldman Sachs, as an investment thesis (Brazil, Russia, India, China).

- 2006 – Governments picked it up

- Foreign ministers of BRIC countries met informally at the UN General Assembly.

- 2009 – First BRIC leaders’ summit

- In Yekaterinburg, Russia

- 2010 – South Africa joined, turning BRIC into BRICS

Who pushed it politically

- Russia and China strongly promoted formalization

- Brazil was an early and enthusiastic adopter

- India initially cautious but engaged

- South Africa lobbied to join and was invited

BRICS was named by a banker, but built by states.

3. Brazil’s real role (important distinction)

Brazil did not invent either project, but it played a strategic catalytic role:

In Mercosur

- Equal partner with Argentina

- Provided economic gravity

- Anchored smaller neighbors

In BRICS

- Early adopter of the BRIC idea

- Actively shaped its agenda

- Pushed development finance (leading to the New Development Bank)

Brazil’s diplomacy has long aimed at:

- Autonomy without isolation

- Multipolarity

- South–South cooperation

4. One key difference between the two

| Aspect | Mercosur | BRICS |

|---|---|---|

| Origin | Governments | Private-sector concept → governments |

| Scale | Regional | Global |

| Structure | Treaty-based | Forum-based |

| Brazil’s role | Co-founder | Early institutionalizer |

Bottom line

- Mercosur was co-founded by Brazil and Argentina through reconciliation and treaties.

- BRICS was conceptualized by a Western economist, then appropriated and built by governments, with Brazil as a core early player.

- Brazil is best described as a builder and stabilizer, not a sole inventor.

Under which Presidency was it created?

Mercosur (Mercosul)

Political origin

- Brazil: José Sarney (President 1985–1990)

- Argentina: Raúl Alfonsín (President 1983–1989)

1985 – Iguaçu Declaration

This is where the idea of Mercosur was politically launched, ending Brazil–Argentina rivalry and committing to integration.

Legal creation (formal founding)

- Brazil: Fernando Collor de Mello (President 1990–1992)

- Argentina: Carlos Menem (President 1989–1999)

1991 – Treaty of Asunción

Mercosur officially comes into existence as a legal entity.

So:

- Conceived under Sarney

- Formally created under Collor

BRICS

Adoption by governments

- Brazil: Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva (President 2003–2010)

2006 – First BRIC foreign ministers’ meeting (UN General Assembly)

2009 – First BRIC heads-of-state summit (Russia)

South Africa joined in 2010, still under Lula, creating BRICS.

So:

BRICS was politically institutionalized under Lula

Clean summary

| Bloc | Brazilian President at creation |

|---|---|

| Mercosur (idea) | José Sarney |

| Mercosur (treaty) | Fernando Collor de Mello |

| BRICS | Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva |

Key insight

Brazil’s strategic continuity matters more than any single president:

- Sarney → reconciliation

- Collor → institutionalization

- Lula → global south leadership

Different ideologies, same long-term foreign policy goal: autonomy through integration.

Here is why Brazil’s foreign policy stays remarkably consistent, even when presidents change and ideologies swing.

1. Brazil’s “state policy” vs. “government policy”

Brazil clearly separates:

- Política de Estado (state policy → long-term, strategic)

- Política de governo (government policy → short-term, ideological)

Foreign policy sits firmly in the state policy category.

Presidents come and go; core objectives remain.

2. The central role of Itamaraty

Brazil’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Itamaraty) is one of the most:

- Professionalized

- Meritocratic

- Autonomous diplomatic corps in the world

Key features

- Career diplomats trained through the Rio Branco Institute

- Strong institutional memory

- Long-term strategic planning

- Relative insulation from party politics

Even presidents with radically different views rarely dismantle Itamaraty’s core doctrine.

3. Core doctrines that don’t change

Across military, liberal, conservative, and left-wing governments, Brazil has pursued:

Strategic autonomy

- Avoid formal military alliances

- Resist alignment with any single great power

- Maintain diplomatic flexibility

Universalism

- Maintain relations with everyone (US, EU, China, Russia, Iran, Africa)

- No permanent enemies

Multilateralism

- Preference for rules-based international forums

- UN, WTO, G20, BRICS, regional blocs

South–South cooperation

- Leadership among developing nations

- Africa, Latin America, Global South coalitions

4. Presidents as accelerators, not inventors

Presidents mostly:

- Accelerate or decelerate existing strategies

- Shift tone, not direction

Examples:

- Sarney → reconciliation & democracy lock-in

- Cardoso → institutional consolidation & WTO engagement

- Lula → Global South expansion & BRICS

- Bolsonaro → rhetorical alignment with the US, but few structural reversals

- Lula (III) → reactivation of multilateralism

5. Why Brazil needs continuity

Brazil’s structural realities force consistency:

- Continental size, no enemies at borders

- Economy dependent on diversified trade

- Military doctrine focused on defense, not projection

- Aspiration to be a rule-shaper, not a rule-taker

Radical swings would be costly and destabilizing.

6. Mercosur and BRICS as proof

- Mercosur survived neoliberalism, leftism, nationalism

- BRICS survived leadership changes and global crises

That endurance signals state strategy, not personal projects.

Bottom line

Brazil’s foreign policy continuity exists because:

- Institutions outlast presidents

- Strategic geography limits choices

- Diplomacy is professionalized

- Autonomy is non-negotiable

Even Brazil’s former president, Jair Bolsonaro, largely accepted the same core foreign-policy doctrine, despite disagreeing with it rhetorically and ideologically.

This is a crucial distinction in Brazil: discourse vs. structure.

Short answer

Bolsonaro criticized and challenged Brazil’s traditional foreign policy — but in practice he did not dismantle it.

He clashed with Itamaraty’s worldview, yet ended up operating within its limits.

What Bolsonaro disagreed with (rhetoric & tone)

Bolsonaro openly rejected parts of Brazil’s diplomatic tradition:

- Criticized “globalism” and multilateral institutions

- Expressed ideological alignment with:

- The Trump administration

- Conservative nationalist movements

- Was skeptical of:

- South–South diplomacy

- BRICS’ political symbolism

- Environmental diplomacy framing

This was unusual by Brazilian standards and caused real friction inside Itamaraty.

What Bolsonaro did not change (structure & facts)

Despite the rhetoric:

BRICS

- Brazil remained fully committed

- Continued participation in summits

- Never left or downgraded BRICS

- Continued involvement in the New Development Bank

Bolsonaro never attempted withdrawal.

Mercosur

- Bolsonaro complained about Mercosur

- Threatened flexibility or reform

- Did not exit

- Did not dissolve the customs union

- Continued negotiations (e.g., EU–Mercosur talks)

Mercosur survived intact.

Strategic autonomy (the red line)

Even Bolsonaro:

- Did not enter formal military alliances

- Did not subordinate Brazil to US strategic control

- Maintained relations with:

- China (Brazil’s largest trading partner)

- Russia

- Middle Eastern and African states

Trade realities forced continuity.

Why Bolsonaro ultimately “agreed” in practice

Three constraints mattered more than ideology:

1. Itamaraty

Career diplomats limited radical shifts and preserved treaties.

2. Economic gravity

China, Mercosur, and BRICS were too economically important to abandon.

3. Congress & Constitution

Foreign treaties cannot be undone unilaterally by a president.

The paradox

Bolsonaro rejected the philosophy

but obeyed the architecture

So the honest answer is:

He did not agree — but he complied.

Bottom line

- Brazil’s foreign policy is stronger than presidents

- Bolsonaro tested the system

- The system held

- Mercosur and BRICS survived untouched

That resilience is precisely why Brazil is considered a “continuity power” rather than a swing state.