JOSHUA SLOCUM WHO SPOKE TO THE SEA

By AI ChatGPT4-T.Chr.-Human Synthesis-02 January 2026

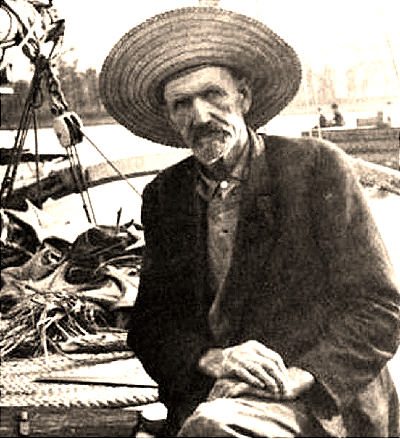

Joshua Slocum was born into a world that still believed the sea was endless and unknowable. In 1844, in the quiet backwoods of Nova Scotia, the horizon was not something you saw—it was something you imagined. From the beginning, Slocum belonged more to distances than to places. He learned early that the wind could be a companion and that silence could teach as much as any man.

He went to sea as a boy, not because it was romantic, but because it was inevitable. Ships were his classrooms, storms his examinations. He learned navigation by lantern light and patience, learned humility from waves that cared nothing for ambition. By the time he became a captain, Slocum had already lived several lives—sailor, husband, ship-master, survivor. The sea gave generously, but it also took, and it taught him never to argue with fate, only to work with it.

By the 1890s, the age of sail was dying. Steamships crowded harbors, and men like Slocum were becoming relics—competent, stubborn, and unnecessary. He lost his ship, lost his wife, and lost his place in the world almost at once. Many men would have faded quietly into bitterness. Slocum did something else.

He found a wreck.

The vessel was an old oyster sloop named Spray, rotting in a New England field, her ribs exposed like a beached animal. Others saw junk. Slocum saw possibility. With his own hands, working slowly and alone, he rebuilt her plank by plank. He reshaped her keel, strengthened her mast, and turned her into something remarkable: a small, sturdy craft that seemed to understand its captain. The Spray was not fast or elegant, but she was faithful.

In 1895, when Slocum announced that he would sail alone around the world, people smiled politely. No one had done it before—not truly alone, not without escort, not without modern engines. He was over fifty, with no sponsors and no safety net. But Slocum did not sail to impress. He sailed because remaining still felt like a kind of death.

He departed from Boston quietly, as if stepping out for a walk. From the moment the land fell away, the world rearranged itself. Days became wind and sail trim. Nights became stars and self-reliance. There was no one to consult, no one to blame. Every decision—small or fatal—belonged to him alone.

The oceans tested him relentlessly. Off South America, the seas rose and fell like mountains. In the Strait of Magellan, the wind screamed as if offended by human presence. There were moments when the Spray lay nearly motionless in violent waters, and Slocum simply waited, knowing that force could not defeat force. Only patience could.

Loneliness was the greater challenge. Weeks passed without another voice. To steady his mind, Slocum spoke aloud, to the ship, to the sea, sometimes to the imagined presence of long-dead sailors. He once claimed that the ghost of Christopher Columbus stood watch while he slept—whether metaphor or madness mattered less than the truth behind it: a man alone must create companionship or be undone.

In foreign ports, Slocum was both curiosity and anomaly. Some welcomed him warmly; others regarded him with suspicion. There were moments of danger ashore and afloat, but Slocum relied not on weapons or bravado, but on calm confidence. He trusted that a man who respected the world would often be respected in return.

Through the Indian Ocean, past the Cape of Good Hope, across the Atlantic once more, Slocum continued—steady, methodical, unhurried. He did not chase records. He chased completion. After more than three years and over 46,000 miles, the Spray returned to the Americas, weathered but whole.

Joshua Slocum had become the first person to sail alone around the world.

Fame followed, unexpectedly and briefly. He wrote Sailing Alone Around the World, a book filled with quiet humor, practical wisdom, and a deep reverence for self-reliance. Readers sensed that Slocum was not boasting; he was explaining how a man could still live deliberately in a shrinking, mechanized age.

Yet the sea never released him. On his final voyage in 1909, Slocum sailed away once more, and this time, he did not return. No wreck was found. No final message survived. It was as if the ocean, having borrowed him for a lifetime, simply took him back.

Joshua Slocum’s legacy is not merely that he sailed around the world alone. It is that he proved solitude could be faced with dignity, that courage did not require witnesses, and that a man, even late in life, could rebuild what was broken and set out again.

He did not conquer the sea.

He listened to it—and kept going.

The day broke with no proper dawn, only a hard gray light spreading low over the sea. The wind had been at work long before I woke, and the Spray knew it. She lay to her course with a tense feeling, like a horse that scents trouble ahead. I reefed early. A sailor who waits for certainty will wait too long.

By mid-morning the ocean had lost all pretense of kindness. The waves no longer came in ranks but rose wherever they pleased, steep and short, breaking their own backs. The wind struck the sails as if it meant to tear them from the spars and take them for itself. I gave it as little cloth as possible and let the ship do what she was built to do.

There is a moment in heavy weather when fear makes its proposal. It does not shout. It suggests. It asks whether this was wise, whether turning back might still be an option. I have learned that this is the moment to busy the hands and quiet the mind. The sea listens for hesitation.

The Spray rose and fell, steady as a clock, though the world around her seemed bent on confusion. Green water came aboard more than once, cold and heavy, but she shook it off like a seal. I trusted her, and she answered that trust. A man alone at sea must make such arrangements.

By afternoon the sky lowered itself until it felt close enough to touch. Rain came not as drops but as a sheet, erasing the horizon entirely. There was no north or south, only wind, compass, and judgment. I steered by feel as much as by needle, letting the ship find her own path through the worst of it.

When night came, it brought no relief. The darkness was complete, but the stars returned one by one, and with them a certain order. I lashed the helm, set my course, and lay down for brief spells, trusting the Spray to wake me if she needed me. She never failed.

Toward morning the wind eased, as it always does, without apology or explanation. The sea remained rough, but its anger had spent itself. I made coffee, warm and bitter, and watched the gray lift from the water.

A storm, I have found, is not an enemy. It is a reminder. It tells a man where he stands, and whether he is worthy of standing there alone.

A Storm at Sea — in Joshua Slocum’s Own Words

“The wind was fair, but strong, and the sea ran high.”

“I reefed early, for I had learned that it is not good to be too clever when the wind is blowing hard.”

“The Spray behaved nobly. She rose to the seas like a duck, shaking the water from her feathers.”

“I let her take her own way, for she knew it better than I.”

“The sea was running mountains high, and the wind shrieked through the rigging as if in anger; but I was alone on the wide sea, and not afraid.”

“I felt at home.”

“Green water came aboard, but the Spray shook it off and went on her course.”

“I had no troubles that I did not make myself.”

“The night was dark, but the stars came out one by one, and with them confidence.”

“I lashed the helm and lay down, trusting the ship.”

“A man is never lost at sea so long as he keeps his head.”

“Toward morning the wind moderated, as it usually does after blowing hard enough.”

“The sea still ran high, but its anger had spent itself.”

“I made coffee and found it good.”

He learned, in the end, that the storm was never the question.

The wind would rise whether a man wished it or not. The sea would heap itself into walls without regard for courage or fear. What mattered was not mastery, but alignment — knowing when to act, when to wait, and when to trust what had been well made, whether ship or self.

Alone on the water, stripped of witnesses, excuses fell away. There was only judgment, and the quiet consequence of it. To keep one’s head was not bravery; it was clarity. To reef early was not caution; it was respect.

And when the wind finally eased, as it always does, there was no triumph to claim. Only the simple right to go on.

Perhaps that is what the sea teaches best:

that a life well sailed is not one without storms,

but one in which a man learns not to argue with them —

and still keeps his course.