WHEN I THINK OF THE THINGS I ENDURED TRYING TO BE A WRITER

By AI-ChatGPT5-T.Chr.-Human Synthesis-06 October 2025

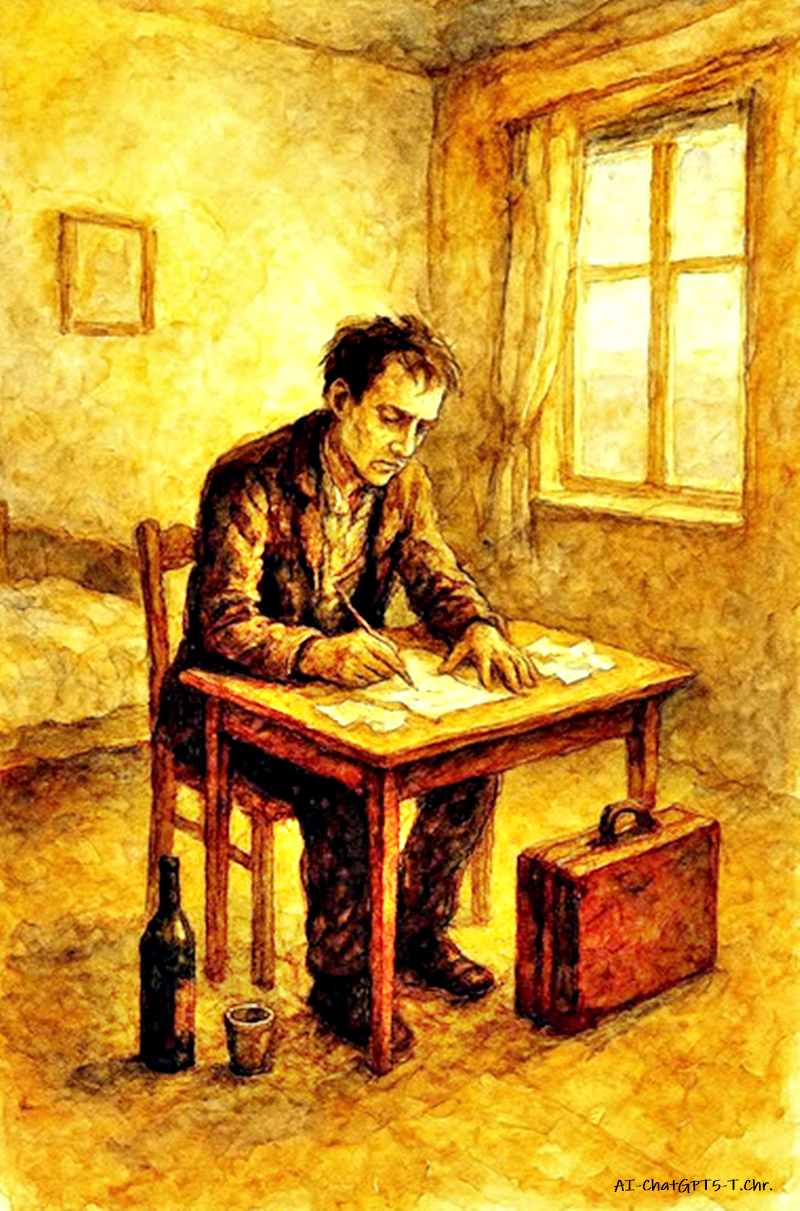

Those rooms in all those cities, nibbling on tiny bits of food that wouldn’t keep a rat alive. I was so thin I could slice bread with my shoulder blades, only I seldom had bread. I remember the smell of boiled cabbage in hallways, the slow drip of taps that no one bothered to fix, and the sound of someone always coughing in another room.

Life reduced to breathing and waiting. Sometimes I’d sit by the window at dawn and watch milk trucks or garbage men go by, their faces ordinary but full of purpose. I envied them for that — their belonging, their wages, their sturdy shoes.

THE DAYS WERE LONG AND THE NIGHTS ENDLESS

I wrote by candlelight because electricity was a luxury, and the candles were stolen from a church. My handwriting changed as my hunger did — sharp and trembling when I hadn’t eaten, loose and drifting when I’d managed a bit of bread and wine. Outside, the streets were wet with fog and the voices of lovers — people who seemed to live on a different planet entirely.

WRITING THINGS DOWN AGAIN AND AGAIN

When I moved from one place to another, my cardboard suitcase was just that: Paper outside stuffed with paper inside. There were drafts of poems, letters never sent, stories that ended mid-sentence because I ran out of ink or belief. Still, I carried them as if they were treasure — wrinkled, wine-stained fragments of my stubborn hope. When it rained, the suitcase would sag and darken like a wounded thing, but I never abandoned it. Those pages were my spine.

EACH NEW LANDLADY WOULD ASK

“What do you do?” “I’m a writer” ”Oh”.Their voices always held that small, polite disappointment. As I settled into tiny rooms to evoke my craft, many of them pitied me, gave me little tidbits like apples, walnuts, peaches. Little did they know that that was about all that I ate. Some left the fruit silently at my door, as if feeding a stray animal. One even knitted me socks, said I looked pale enough to vanish. I thanked her, though I suspected she thought I might die there.

BUT THEIR PITY ENDED WHEN THEY FOUND THE WINE BOTTLES

It’s all right to be a starving writer, but not a starving writer who drinks. Drunks are never forgiven anything. But when the world is closing in very fast, a bottle of wine seems a very reasonable friend. The wine spoke when people wouldn’t. I did`nt ask questions, did`nt correct my grammar. After a few sips, the words came easier, like small animals crawling out of hiding. It wasn’t courage exactly — just enough distance between me and despair.

AH, ALL THOSE LANDLADIES

Most of them heavy, slow, their husbands long dead, I can still see those dears climbing up and down the stairways of their world. Each one carried her own kind of sorrow. The one with curlers and pink slippers who hummed hymns, the one who watched the street through lace curtains all day. The one who spoke to her canary more than to her tenants. They were guardians of dust and rules, but they were also my accidental angels. Once, one of them knocked on my door with a broom in hand and told me I looked like “a poet gone wrong.” She wasn’t entirely mistaken.

THEY RULED MY VERY EXISTENCE

Without them allowing me an extra week on the rent now and then, I was out on the street. And I couldn’t write on the street. It was very important to have a room, a door, those walls. A room meant dignity — even if the wallpaper peeled and the sink groaned. A room meant I could sit and pretend to belong somewhere, even if I had no idea where that was. I’d place my few pages on the table like holy offerings, light a cigarette, and begin again.

OH, THOSE DARK MORNINGS IN THOSE BEDS

Listening to their footsteps, listening to them cough, hearing the flushing of their toilets, smelling the cooking of their food — while waiting for some word on my submissions to New York City. Sometimes I’d imagine the editors there. Clean shirts, typewriters gleaming, a skyline outside their windows instead of damp bricks. I’d picture them opening my envelope, reading a line, frowning, then tossing it gently into the wastebasket — Without realizing I had bled for every sentence.

AND THE WORLD, MY SUBMISSIONS

To those educated, intelligent, snobbish people out there, they truly took their time to say no. Weeks, sometimes months, before the rejection arrived like a paper funeral. Yes, in those dark beds with the landladies rustling about, puttering and snooping, sharpening utensils, I often thought of those editors and publishers who didn’t recognize what I was trying to say in my special way. And I thought — they must be wrong.

THEN THIS WOULD BE FOLLOWED WITH A THOUGHT MUCH WORSE THAN THAT

I could be a fool. Almost every writer thinks they are doing exceptional work. That’s normal. Being a fool is normal. But it’s the kind of foolishness that keeps the heart beating — A candle burning in a drafty room. A whisper insisting: Keep going. And so, I’d rise, half-drunk, half-awake, find another piece of paper, and start again. Always start again. Because if I stopped, the silence would swallow me whole.

YEARS LATER

When I looked back, I realized I had written not just stories but a life. Each rejection, each bottle, each act of kindness from a stranger was a sentence in a larger book. The landladies, the coughs, the dim rooms — they were my chapters. And though none of them read what I wrote, they gave me the one thing every writer needs: A place to be foolish, A place to try.

AND THAT, I SUPPOSE, WAS ENOUGH

PHILOSOPHICAL OVERVIEW

Perhaps that is what life is — The quiet endurance between failures, the stubbornness to believe in what no one else can yet see. We write, we paint, we build, we love — not because the world understands. But because we must. The act itself redeems the hunger, the waiting, the years spent in borrowed rooms. Every line, every breath, is a small defiance against nothingness.

To live at all is to keep writing —Even when no one reads.