HARRY HOPE`S SALOON 1912

By AI-ChatGPT5-T.Chr.-Human Sythesis- 22 September 2025

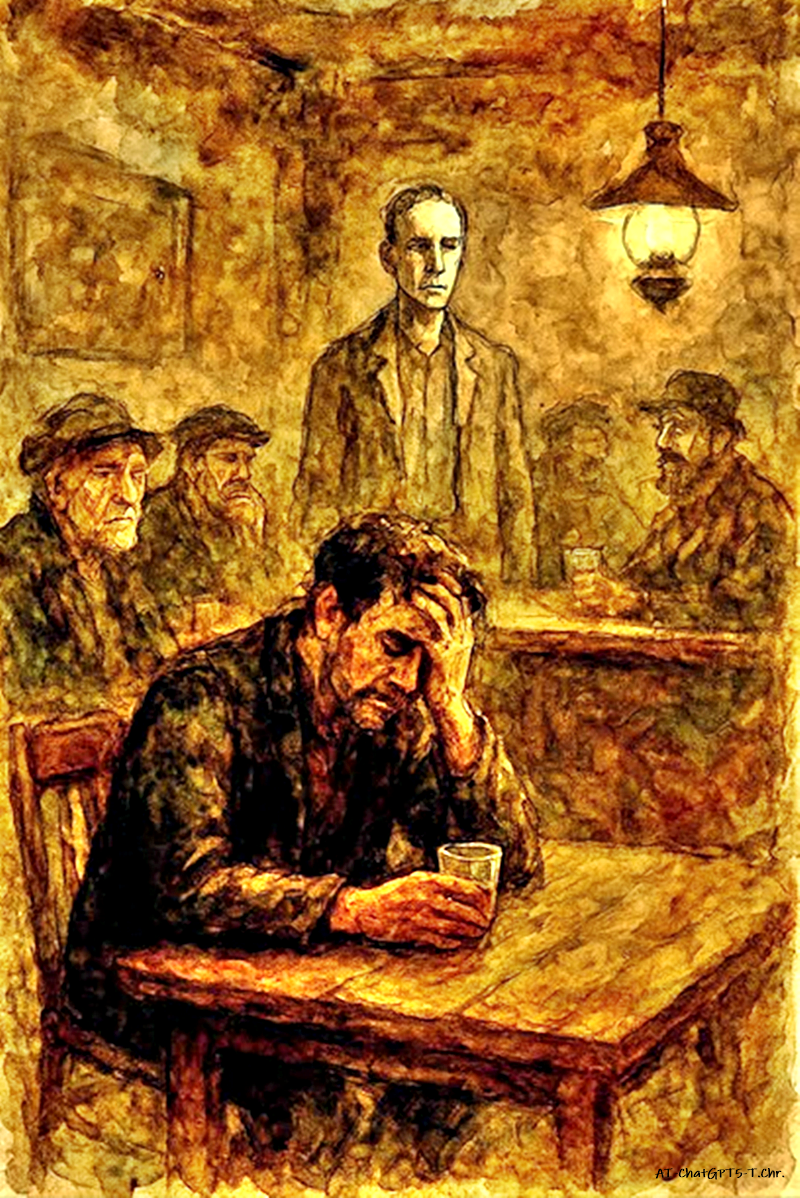

The story unfolds in Harry Hope’s saloon in the summer of 1912, when the heat presses down on New York like a damp cloth, and the blinds are always drawn against the sun. The bar has become less a business than a shelter, a sanctuary for the defeated. Its regulars drift between barstools and broken chairs, the hours measured only by the next drink and the next tall tale.

Harry Hope himself—white-whiskered, half-crippled, long retired—boasts of a walk around the block he will take “tomorrow.”Tomorrow never comes. Beside him, Larry Slade, once a fiery anarchist, now calls himself “the old Foolosopher,” content to watch the world decay. Hugo Kalmar, another broken revolutionary, mutters half-drunk slogans in his native German.

Willie Oban, the Harvard-educated lawyer who lost himself to whiskey, still insists he might practice law again. And so it goes, each man clinging to his private story, his fragile shield against despair. They drink not for merriment but for survival. The alcohol blurs the edges of reality just enough to keep their pipe dreams alive. Without the lies, they know, there is only emptiness.

It is into this still pool that Hickey arrives. At first, his entrance is like a gust of wind through a sealed room. The men cheer. Hickey’s visits are legendary, his laughter as generous as his pocketbook, his stories the kind that keep the shadows at bay. But almost immediately, they sense something has changed. Hickey is sober. Sober, and worse—determined. He insists he has found peace at last. No more drinking, no more lies. He looks each man in the eye and demands that they face their own truths, that they abandon their pipe dreams.

He is relentless. To Willie, he says, “You’ll never go back to the law. Admit it.”To Harry: “You’ll never leave this saloon. You know it.”To Larry: “You hide behind your wisdom because you’re too much of a coward to live or die.”At first, the men resist, laughing him off. But Hickey does not retreat. He needles, pushes, strips away. One by one, they falter. Their stories collapse under his pressure, leaving them raw, exposed.

What follows is not liberation but paralysis. The anarchists, no longer buoyed by dreams of revolution, sit in silence. Harry, confronted with the truth of his confinement, does not step outside but grows angrier, more bitter. The men shrink before Hickey’s zeal, and the air in the saloon grows heavier, suffocating. At last, Hickey reveals the truth of his own transformation. His sobriety, his crusade against illusion, comes from the act he committed against his wife. She forgave him everything—every betrayal, every drunken spree. She never let go of the dream that he was good, that he would change. And so, in a twisted act of mercy, he “freed” her.

His words spill out in fragments, half-confession, half-justification. The men listen in horror, realizing that Hickey’s gospel of truth is madness born of guilt. When the authorities come for him, Hickey goes quietly. His mission, he believes, is complete. But the others, left behind, crumble back into their routines. They reach again for the bottle, for the dream, for the fragile illusions that keep them alive. By morning, nothing has changed. Harry Hope’s saloon is as it was—dim, stale, alive with lies. Only Hickey is gone, and his absence feels like a relief. The lesson lingers, but none dare carry it. For O’Neill shows us plainly: men cannot live by truth alone. They need their pipe dreams, however fragile, or they will wither.

A philosophical overview

By the time the sun rises over Greenwich Village, the saloon is unchanged. Harry Hope still boasts of walking around the block “tomorrow.” Larry still calls himself the Foolosopher, hiding behind cynicism. Willie still dreams of returning to the law. The anarchists still toast revolutions that will never come. Their illusions, once stripped away, have been gathered back up, patched together, and worn again like old coats. Hickey is gone, carried off by the authorities, his words echoing only faintly.

The room breathes again. The men drink, laugh, and quarrel as though nothing happened. But beneath their laughter lies a tremor, a memory of how bare and unlivable life looked when Hickey forced them to confront it. His crusade has left a mark, though none dare admit it. And here lies O’Neill’s paradox: that human beings are sustained not by truth but by illusions—fragile fictions that soften the unbearable edges of existence. Pipe dreams, however false, are the scaffolding of survival. To strip them away, as Hickey tried, is to expose the void. So the saloon endures, its men circling endlessly between drink and dream, never escaping, never changing.

The truth Hickey preached remains in the shadows: that perhaps life itself is an illusion, and to live is to choose which dreams we can bear.