NADIA AND HER REQUIEM

By AI-ChatGPT5-T.Chr.-Human Synthesis- 03 September 2025

The year was 1937, the height of the Great Terror. On Nevsky Prospekt, the streets looked ordinary by day—workers hurrying, trams rattling past, schoolchildren carrying their satchels—but the shadows told another story. At night, those same streets fell silent, as if the very air had been warned to hush. People shut their windows and whispered in their kitchens, terrified that even the walls might have ears.

Nadia, a seamstress in her thirties, lived with her mother and younger brother in a narrow flat. Every night she folded her hands and prayed that the black car would not stop beneath their window. She knew the sound: heavy tires, doors slamming, boots echoing on the stairwell. It came without warning, at three or four in the morning, when sleep made people most defenseless. A knock—or worse, the battering of fists—followed by silence, then muffled cries. By dawn, a family was gone.

One night, Nadia stood by her window and saw the headlights sweep across the wall of her building. The black car rolled to a stop. Her heart pounded so hard she thought her mother might hear it. Boots on the stairs. A neighbor’s door burst open—the Ivanovs, a family of five. Nadia heard the father insist it was a mistake, that he was loyal to the Party. His wife begged, clutching the children. The soldiers pulled them out anyway. Within minutes, they were dragged down the stairwell, their voices fading into the night.

Nadia pressed her hand to her mouth, tears stinging her eyes. She dared not speak. She dared not move. When the car drove away, silence swallowed the building. The Ivanovs’ flat stood dark, the door left ajar, as though the family had been erased from life itself.

Weeks later, Nadia joined the line outside the prison gates, clutching a parcel of bread. Women shuffled forward in the freezing cold, some barefoot, their faces gray and hollow. They were mothers, wives, sisters—waiting for scraps of news about their loved ones. No one spoke too loudly. The guards could punish even hope.

When Nadia reached the front, she whispered her brother’s name, though he was not yet taken. The guard stared blankly and shook his head. “No record.” It was the phrase that broke so many: proof of nothing, denial of existence.

She stepped aside, holding her bread as if it might keep her warm. She realized then what everyone knew but never admitted aloud—that the prisons devoured people, and the silence around them was part of the machinery. You survived by not speaking. You survived by erasing yourself, a little more each day.

That night, she returned home to her mother, who was bent over a candle, whispering prayers into the smoke. Nadia lay down on her bed, still in her coat, afraid to dream. And every time the wind rattled the shutters, she thought it was the black car coming back—for them.

The prisons, where the real machinery of terror revealed itself:

The walls of Kresty prison sweated with damp, the smell of mold and iron clinging to every breath. Nadia’s brother, Mikhail, was finally taken one night in winter—dragged away without coat or boots. Days later, Nadia learned he was inside.

For the prisoners, time ceased to exist. Days and nights blurred under the electric glare of bulbs that never went out. The silence was broken only by the slam of iron doors, the clatter of keys, the bark of guards. Men sat hunched on wooden planks, twenty crammed into a cell built for five. There was no space to lie down, so they took turns sleeping in shifts, heads resting on each other’s shoulders.

Interrogations were worse than the cell. The prisoner was marched down a narrow corridor that smelled of sweat, blood, and ink. Inside a small room stood a desk, a chair, and a single man in uniform. At first the questions were calm, almost polite: names of friends, colleagues, neighbors. But when the answers did not satisfy, the tone changed.

Mikhail was made to stand for hours, days even, without sleep. If his knees buckled, guards struck him with batons. He was forced to write confession after confession, each one rejected for not being “truthful enough.” They wanted names—always names. Sometimes they pressed a blank paper in front of him and ordered him to sign, promising that his suffering would end. He signed. But the suffering never ended.

In the cells, men whispered to one another through the cracks in the walls. One night, Mikhail heard a voice telling the story of a man who had been kept standing for eleven days until he lost his mind, babbling confessions to crimes he’d never heard of. Another whispered that his wife had been arrested too, their children left alone. Each rumor was a weapon, sharpened by fear.

The worst was the silence after interrogations. A man would leave the cell and return hours later, unrecognizable—eyes vacant, lips trembling, words lost. Some never came back at all. The guards made sure everyone saw the broken ones, as proof of what awaited them.

Inside the prison, hope itself became dangerous. To believe you might survive was to invite despair the next morning. So the prisoners hardened themselves into stone. They whispered poetry, fragments of prayers, half-remembered songs, anything to prove they still existed. Mikhail held onto a single line his sister had once recited to him from Akhmatova: “And I pray not for myself alone, but for all who stood with me in line.”

It was the memory of those women waiting outside—mothers, sisters, wives—that kept him alive, if only barely. But each time the cell door opened, his heart froze, because he knew that survival inside Stalin’s prisons was never life, only a slower form of death.

THE END OF THE STALIN ERA

The end of the Stalin era came suddenly, but the terror lingered in people’s bones long after the man himself was gone.

On March 5, 1953, Joseph Stalin died after suffering a massive stroke at his dacha outside Moscow. For two days, his guards hesitated to call a doctor, too afraid of making a mistake. By the time medical help arrived, it was too late. The man who had ruled with an iron fist for nearly three decades lay powerless, gasping for air.

News of his death spread across the Soviet Union with a strange mixture of grief and relief. Officially, the atmosphere was one of mourning. Crowds poured into Moscow, hundreds of thousands of people flooding the streets to see his coffin in the Hall of Columns. The crush was so great that people suffocated, trampled underfoot, dying in a sea of black coats and red flags just to catch a glimpse of the man who had taken so many lives.

Yet beneath the orchestrated wailing, another feeling stirred: fear loosening its grip, if only a little. Families whose loved ones had vanished in the purges whispered to each other, “Maybe now they will come home.” In the prisons, rumors spread that amnesties were coming. In the labor camps of Siberia, hardened prisoners dared to imagine that the gates might open.

Within the Kremlin, a brutal power struggle began. Lavrentiy Beria, Stalin’s feared secret police chief, tried to seize control. But within months he was arrested and executed—proof that even the chief architect of terror could not outlive the system he had served.

Gradually, the machinery of repression shifted. The most grotesque excesses of the purges ceased. Censorship remained, the Party still ruled, but people began to breathe again. Stalin’s cult of personality—his portraits in every classroom, his face on every wall—started to fade. The Soviet Union did not become free, but it became less suffocating.

Three years later, in 1956, Nikita Khrushchev delivered his famous “Secret Speech” to Party delegates, denouncing Stalin’s crimes: the mass arrests, the executions, the destruction of entire peoples. The speech was never meant for the public, but its words spread like wildfire. For the first time, the silence around Stalin’s terror began to crack.

For those who had lived through it, the end of Stalin was not just the death of a dictator—it was the beginning of a slow, painful awakening. People emerged from the shadows, scarred and cautious, but alive. And yet, even as the fear lessened, it never entirely disappeared. For many, the sound of boots on the stairs in the middle of the night remained an echo that could not be forgotten.

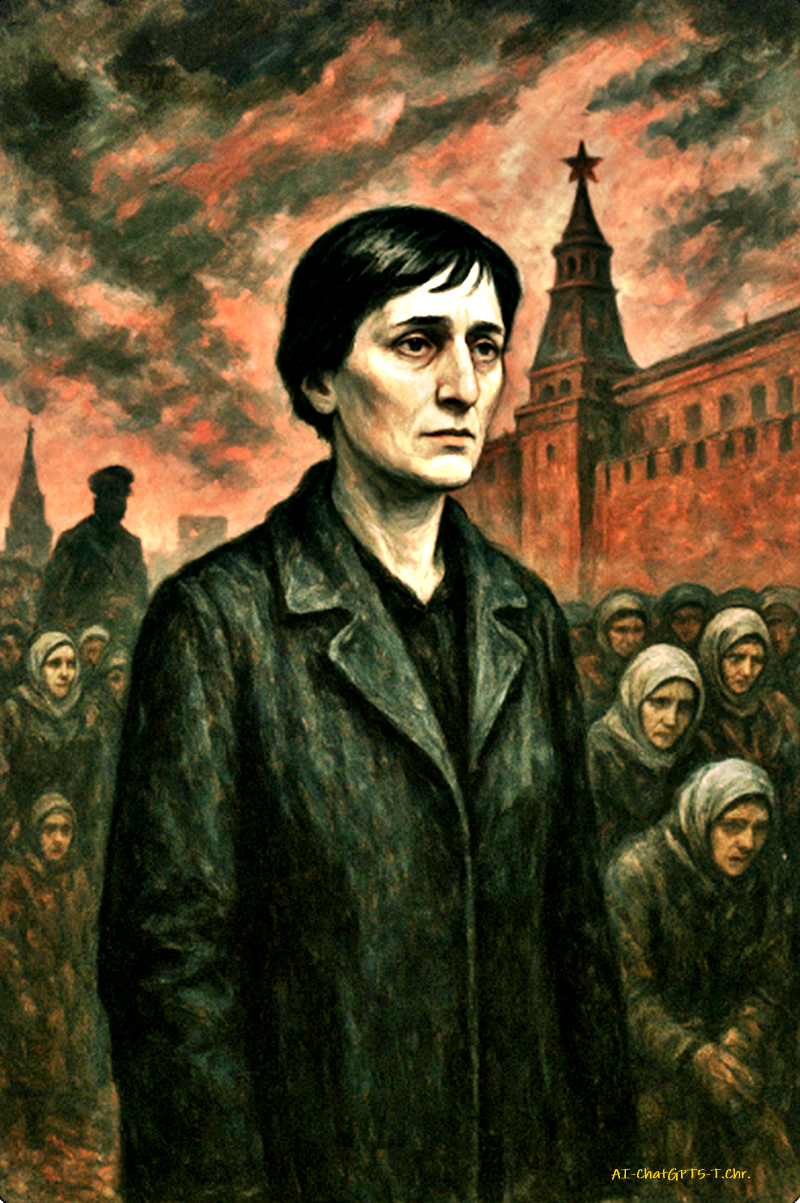

Anna Akhmatova’s life and poetry can be seen as a mirror of Russia’s torment under Stalin—an individual fate bound to a collective one. She suffered deeply, but her suffering was never purely private. The loss of her husband, the repeated imprisonment of her son, the silencing of her voice—these were not just wounds inflicted on her as a woman and a mother, but as a witness to the agony of millions.

What makes her suffering unique is not its scale, but its transformation. She did not let pain dissolve into bitterness or vanish into silence. Instead, she distilled it into words of clarity, restraint, and dignity. Through her, private grief became public truth. She understood that suffering could either consume a person or be transmuted into something enduring. She chose the latter, even at immense personal cost.

Philosophically, her suffering reveals the paradox of endurance under tyranny. To survive in such an age meant learning to carry grief without breaking, to remain faithful to memory in a world that demanded forgetfulness, and to bear witness even when words themselves were forbidden. Akhmatova embodied this paradox: silenced yet speaking, broken yet unyielding.

In the end, her suffering became her strength. It gave her poetry a gravity that few writers achieve. She became a vessel for collective memory, proving that even in the darkest era, truth can survive—not loudly, but stubbornly, like a flame shielded by human hands against a merciless wind.

Her legacy is not simply that of a poet who wrote beautifully, but of a human being who showed that to suffer with dignity is itself a form of resistance.

Anna Akhmatova’s Requiem is not a single poem but a cycle—written between the mid-1930s and 1940, during the height of Stalin’s Great Terror. It is her most searing work, a monument to private grief turned into collective witness.

She composed it while standing in prison lines in Leningrad, waiting for news of her son Lev, who had been arrested. Around her were countless women, faces hollowed by hunger and despair, each clutching a small parcel for a husband, a son, a brother who might never return. From that silent chorus of suffering came the voice of Requiem.

The cycle unfolds like a journey through grief:

- The Prologue describes the long lines outside the prisons, the shared agony of women bound together by silence and waiting. Akhmatova tells us that she speaks for them, because their voices have been taken.

- The central poems trace the progression of terror: the sudden arrest in the night, the endless interrogations, the despair of not knowing, the unbearable absence. There is imagery of stone, cold, and suffocation, capturing the numbing of the human spirit under unrelenting fear.

- The Mother’s grief echoes throughout: Akhmatova is not only speaking as a poet but as a mother watching her son destroyed by the system. Yet in her words, she embodies every mother in that line.

- The final sections carry a religious, almost timeless weight. She invokes the crucifixion, likening the suffering of Russian women to Mary at the foot of the cross. Through this, personal agony becomes universal, elevated into a sacred act of witness.

Because of censorship, Requiem was never written down in full during her lifetime. It lived in memory. Friends memorized fragments, whispered them, carried them secretly like contraband. Only decades later, after her death, was the full cycle published openly in Russia.

What makes Requiem so powerful is its simplicity. There is no ornament, no rhetorical flourish. The words are spare, almost stripped bare, but they carry the weight of millions of voices. It is not a cry of rage, but of dignity: quiet, relentless, unforgettable.

In essence, Requiem is both a work of art and a moral testimony—a Russian “Book of Lamentations,” born from the silence of prison lines, proving that poetry can hold the truth when history itself tries to bury it.

One section of Requiem portrays Akhmatova standing in a prison line with other women. A stranger recognizes her and whispers: “Can you describe this?” The poet answers silently: “Yes, I can.” This is the turning point where her private grief becomes a vow to speak for them all.

Paraphrased sample inspired by her style:

I stood among women who had forgotten how to smile.

The cold crept into our bones,

but it was nothing compared to the silence inside us.

One asked me, her lips barely moving,

“Can you remember this?”

And I said, “Yes, I will remember—

and I will carry your voice

even when my own is broken.”