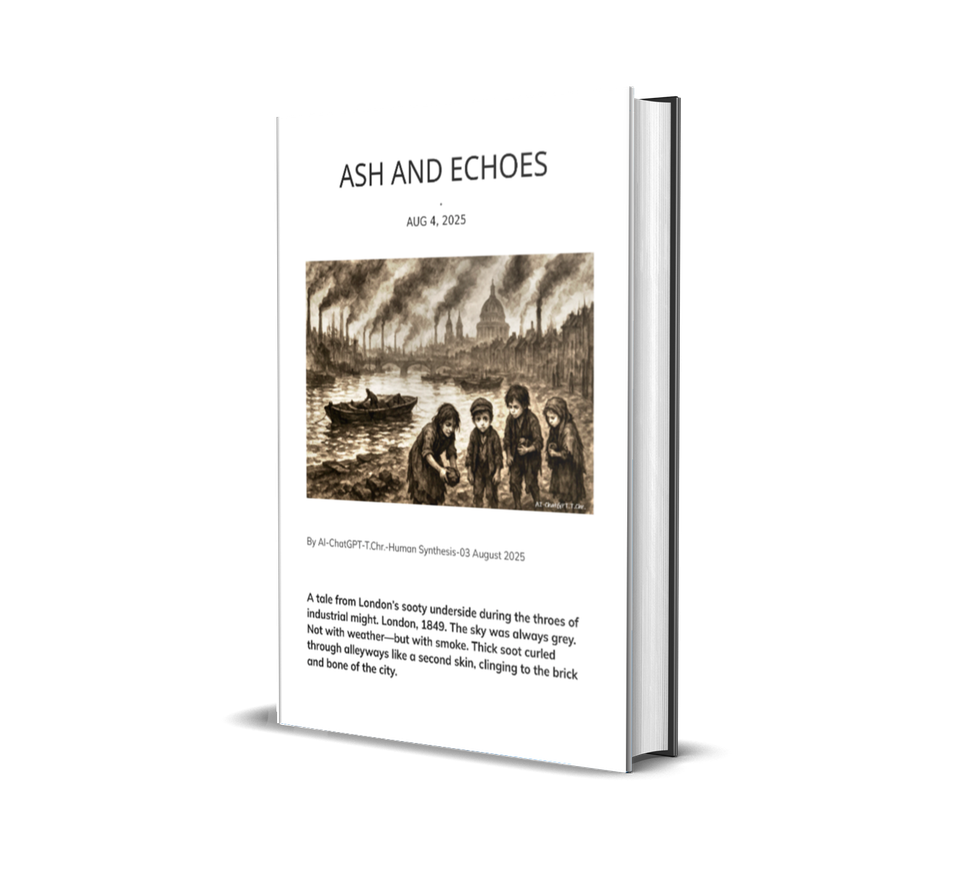

ASH AND ECHOES

By AI-ChatGPT-T.Chr.-Human Synthesis-03 August 2025

A tale from London’s sooty underside during the throes of industrial might. London, 1849. The sky was always grey. Not with weather—but with smoke. Thick soot curled through alleyways like a second skin, clinging to the brick and bone of the city.

The clang of iron and hiss of steam never stopped. Even at night, the factories of Lambeth murmured like great sleeping beasts, coughing smoke into the air, breathing in souls.

Beneath this smoke-hung skyline lived Elias Cobb, a twelve-year-old chimney sweep with soot in his lungs and poetry in his heart. He had been sold by his mother for a half-crown and a loaf of bread to a master named Cribben, a bent man with iron knuckles and a fondness for gin.

Elias slept in a coal shed behind the gasworks and worked until his bones ached and his hands blistered. But even amid hardship, Elias found fragments of beauty—snatches of song from a lamplighter, a chalk drawing on a stone wall, or the warm glance of Maggie Finn, a girl from the matchstick factory who sang Irish ballads under her breath as she worked.

Their world was one of cogs and chains. The city’s elite lived on high streets lined with gas lamps and lace curtains. Below, in The Rookery, the slums festered. Children died with blackened lungs; women stitched shirts for pennies until their eyesight failed; and men—when they had work—labored twelve hours a day just to keep a crust of bread on the table.

But rebellion brewed beneath the grime.

At the heart of this slow-burning resistance was Dr. Thaddeus Wren, a disgraced physician turned underground teacher. Once a Royal Society man, he had been ousted for suggesting the poor were not biologically inferior but victims of a system built to grind them down. Now, in a forgotten warehouse behind St. Giles, he taught factory children by candlelight—reading, writing, thinking. Elias and Maggie found their way to him through a network of night whispers and shadowy maps drawn in soot.

“Truth,” Wren said one night, “is not in the numbers they print in ledgers, but in the lungs of children who can't breathe.”

It was here that Elias discovered his voice. He began writing poems on rags and walls, using bits of chalk and grease. “We are not machines,” he scrawled once across the wall of the Old Tannery. The next day, the words were scrubbed off, but not before a dozen workers saw it and whispered, who wrote that?

Maggie, meanwhile, led quiet sabotage in the match factory. The women risked beatings and dismissal, but under Maggie’s coaxing they began to slow the machines, mispack the boxes, and whisper stories of better days. “They want us small and silent,” she said, “but stories make us bigger.”

It couldn’t last forever.

One freezing November, Wren was arrested. They found a pamphlet titled The Soul is Not for Sale in his coat. They said it was sedition. The judge sentenced him to seven years transport. He only smiled and said, “You cannot exile an idea.”

But the idea stayed.

Elias, now fifteen, took up Wren’s torch. By then, he had gathered a following—young factory workers, ragpickers, washerwomen. They met in tunnels, old bakehouses, crypts. They called themselves The Breathers—those who refused to let the smoke choke out their humanity. They passed around dog-eared copies of Shelley, wrote songs of protest, and carved tiny symbols into the cobblestones of Clerkenwell—a small flame inside a wheel.

The authorities never fully understood it. They cracked skulls and jailed a few, but each time a child cried out against injustice, another candle lit. Elias’s poem “Ash and Echoes” was found later, long after the boy had vanished into the prison barges:

Let the smoke rise high and bitter—

We are not your ash to sweep.

Beneath the soot, our hearts still flicker,

We are dreamers. We are deep.

Steel may bend us, cold may break us,

But no empire can remake us.

Ash and Echoes is a haunting ode to the forgotten souls of industrial London—those who lived and died in the city’s shadow but dared to dream in defiance. It is a reminder that even in the darkest smog, the human spirit flickers, fragile—but unyielding.

In 1853, during what was called The Long Black Winter, the coal barges stopped coming up the Thames for weeks. Ice froze the flow of the river. Factories slowed. Hunger bit harder. In the East End, soup kitchens overflowed. So did resentment. It was during this bleak, bone-chilling time that The Breathers made their most daring move.

By then, Maggie Finn had become a legend among the match girls. She was gaunt, coughing blood, but refused to rest. She had smuggled Elias’s verses into the houses of Parliament’s servants, slipping them into coat pockets and under silver trays. One message ended up in the study of a Member of Parliament—a cautious, reform-minded gentleman named Lord Whitcombe, who quietly sympathized with the plight of the poor.

He summoned Maggie secretly. She wore her best patched shawl and stood before him with the defiance of a queen.

“I am told,” he said, “you have fire in your words.”

“I have fire in my bones,” she replied. “And ash in my lungs.”

Whitcombe agreed to help smuggle printed copies of Elias’s manifesto—We Are Not Gears—into country estates and university libraries, stirring quiet scandal among the young aristocracy.

But the authorities struck back.

One fog-heavy night, Cribben, now working as an informant, led constables to the crypt under St. Martin’s Lane, where Elias and his fellow Breathers held a clandestine gathering. Elias was caught, half through reading a new verse. He did not resist. He handed his notebook to a child beside him, whispering, “Remember it all. Say it aloud. Make it louder.”

He was taken to Cold Bath Fields Prison, where men disappeared like steam. But he refused to speak to his captors, refused to give names. The guards grew frustrated. They broke his ribs, starved him, but he only smiled through broken teeth.

Word of Elias’s arrest spread like wildfire. The Rookery boiled with quiet rage. Match girls walked out. Miners in Kent went silent for a day. Carters, blacksmiths, sweepers, beggars—they wore grey scraps of cloth on their sleeves in mourning. No one organized it. It simply happened.

And then—he vanished.

The records claimed Elias Cobb died of consumption. His grave was unmarked, tucked behind the prison wall. But Maggie never believed it. Nor did the children he taught, nor the old, scarred men who'd once stood beside him in the tunnels. They said the guards saw only smoke in his cell one morning—thick and strange—and when it cleared, the boy was gone.

But on the wall of the cell, carved in iron nail:

You can lock the body, not the breath.

You can bury fire, but not death.

We are still breathing.

Epilogue – 1871

A new child, rosy-cheeked and barefoot, ran through the cleaner streets of a changing London. Railways hummed above, the factories moved outwards, and new schools opened, bearing names like The Elias Cobb Institute. In a classroom hung a charcoal drawing: a young boy with soot-smeared cheeks and bright eyes. Below it, his verse.

The Breathers had become legend, their names faded, but their breath still moved the city forward—in quieter machinery, in fairer wages, in ink and speech.

And Maggie Finn? Old now, her voice reduced to a rasp, still sang songs on the banks of the Thames to children who gathered to listen. Some said she’d once led a revolution. She only smiled.

“No,” she’d say, “I just kept breathing.”

Ash and Echoes closes not with fire, but with breath—with the soft, stubborn persistence of the human soul, and the quiet revolution that begins when even one voice dares to whisper against the din:

“We are not machines.”

Chapter: The Girl Who Danced on Chimneys

Before she was called “Sabi,” she was just Jina, born under canvas on a wind-swept field outside Bristol, the daughter of acrobats and dreamers. Her first cradle was a wicker basket wrapped in velvet, her lullabies the roar of lions and the low notes of a calliope.

Life in the Lune & Lark Travelling Circus was one of constant motion—juggling under starlight, dancing between tents, leaping from trapezes into her father’s arms. Her family were outsiders, nomads of joy in a world sinking into smokestacks.

But fate, ever cruel in industrial times, turned quickly. An outbreak of fire—perhaps arson, perhaps accident—reduced the circus to ash. Jina, then nine, was found weeping beside a singed clown's hat by the edge of a railway track. She was taken in by a grim parish orphanage in Southwark, where laughter was considered a sin.

She didn’t last long there.

Jina was too alive. Too much sun in her veins. She was caught doing cartwheels in the chapel aisle, coaxing smiles from silent girls, turning rags into puppets that whispered stories of the road, of stars above fields and the magic of a warm hand in yours. The nuns called her disobedient. A mischief. A “distraction from suffering.”

But her fate changed once more when Simon Loegrind, the schoolmaster from Bruetown, visited the orphanage during a lecture tour about “Moral Reconstitution Through Order.” He saw Jina—dirty-kneed, bright-eyed, drawing a picture of a flying elephant on a page from Leviticus. He intended to correct her.

But she looked up at him with such unfiltered curiosity, such unshaken joy, that something—though he would never admit it—cracked inside him. He adopted her, perhaps as a project, perhaps as a test. Or perhaps because something in her reminded him of a part of himself long buried.

Jina arrived in Bruetown like a breeze through the black fog.

In the Loegrind household—cold, silent, devoted to fact—she was a living contradiction. She sang during chores, painted her fingernails with beet juice, and once tied strings to tea cups to make a “porcelain puppet theatre.” She whispered to Gorm and Susie stories of flying horses and invisible lions. At first, they scoffed. But over time, they listened.

It was Jina who pulled Susie from her shell of numbness. Who secretly stitched bright thread into the hem of her dull grey dress. Who once snuck into Thomas Fielding’s drawing room and replaced a grim ledger with a folded paper bird. “He never even noticed,” she giggled.

Jina's defiance was quiet, but profound. She didn't fight the system with fire or pamphlets—she fought it with imagination. In a town where children were punished for playing, she painted faces on stones and gave them names. In a school where poetry was banned, she recited verses backwards, calling it "linguistic reversal exercises.” Even Simon Loegrind, in moments of solitude, would find himself smiling at her oddities, though he’d mutter curses under his breath.

But Jina’s greatest influence was on Gorm.

The boy, raised to worship rules and suppress all emotion, was drawn like a moth to her warmth. She taught him how to juggle coal lumps. How to turn guilt into a story and fear into a song. She once told him, sitting under the soot-stained sky, “You are not made of iron. You are not a gear. You are you. That’s enough.”

Years later, when Gorm faced a moment that would have dragged him into full corruption, it was Jina’s words that saved him. Her laughter that echoed in his memory when all else felt silent.

Finale: The Lady of Lantern Street

Jina never became a revolutionary. She didn’t vanish in a prison or etch slogans into stone. She stayed in Bruetown. Grew older. Opened a tiny shop lit with colored lanterns. Sold painted toys, miniature masks, spinning tops carved from scrap wood. Poor children came just to look. She let them.

Her circus never returned. But in her shop, in her smile, it lived again.

People called her The Lady of Lantern Street. They said her windows glowed even on the darkest days. That if you stood outside on winter nights, you might hear faint music, like a calliope, and smell roasted chestnuts and sawdust. That stepping into her shop felt like stepping out of time.

Jina Sabi never forgot her roots.

And Bruetown, for all its smokestacks and scars, never forgot her.

In a time of fire and iron, when the world tried to stamp out softness, one circus girl danced lightly above the grime—reminding everyone that joy, too, is resistance.

Philosophical Overview: The Poor and the Machine Age

The Industrial Age arrived like a great steel tide—glittering with promise, rumbling with power—and swept across the lives of the poor with the force of inevitability. It promised progress, but delivered it unequally. For the rich, it offered palaces of glass, railways of speed, fortunes built from coal. But for the poor, it replaced the rhythms of earth and sky with the shriek of whistles and the grind of gears. They became the fuel—flesh turned to labor, breath turned to output, dreams turned to ash.

Philosophically, the Industrial Age marked a severing of human life from nature’s wisdom. Where once the poor sowed fields and watched the seasons, now they watched clock faces and obeyed machines. The dignity of craft—of knowing what one made and why—was swallowed by the cold logic of mass production. A weaver became a button-pusher. A smith became a shadow in a factory row. The soul was decoupled from the hand.

What emerged was a new form of servitude: mechanized poverty. The poor did not lack work—they worked constantly—but they lacked ownership of anything their hands touched. They lived in rows of blackened terraces, coughed their lives into buckets, and were told that their suffering was the price of progress. And yet, the promises made to them—social mobility, meritocracy, advancement—were as hollow as the iron pipes in the mills.

Worse still, the age introduced a subtle cruelty: it demanded gratitude. Children working twelve hours were told they were lucky to have work. Women twisting matchsticks for pennies were told they should be thankful for the factory roof. Poverty was no longer a tragedy—it was a failing. It was blamed on the poor themselves, their lack of discipline, their supposed inferiority. The new gospel of utilitarianism, obsessed with maximizing output and reducing human worth to statistics, gave a moral cover to exploitation.

And yet—even in the darkest corners of soot-stained cities—the human spirit survived.

The poor were not passive victims. They organized, resisted, remembered. They created underground schools, shared bread when none had enough, sang songs when silence was demanded. They told stories to their children not of the machines, but of the stars. They stitched dignity into rags and defiance into prayer.

The philosophical tragedy of the Industrial Age is not that it brought change—but that it forgot the soul in pursuit of the system. It mistook human beings for machines. It glorified logic but neglected compassion. It calculated everything—except the cost to the human heart.

But within this tragedy lies the awakening: that no matter how powerful the factory, how loud the gears, how smoky the sky—the poorest among us have always remembered what it means to be human. They carry the fire. Not in engines, but in stories. Not in ledgers, but in lullabies. Not in profits—but in each other.

And so, as the world turned faster and colder, the poor held on—not just to survive, but to remind the rest of us that life cannot be measured in output alone. It must be lived, felt, wept, danced. Even if only in the shadows of the great machine.