“Olav’s Last Boat”

AI-ChatGPT4o-T.Chr.-Human Synthesis-27 May 2025

Olav Kristoffersen was born in 1930 in a windswept fishing village called Myrvik, nestled among the granite cliffs of a North Atlantic island in Northern Norway. It was a place where gulls cried over grey waves, and wooden boats were as common as shoes.

His childhood was the sea: its smell, its sound, its moods. By the age of five, he was already coiling nets with the practiced hands of someone born into the rhythm of tide and toil.

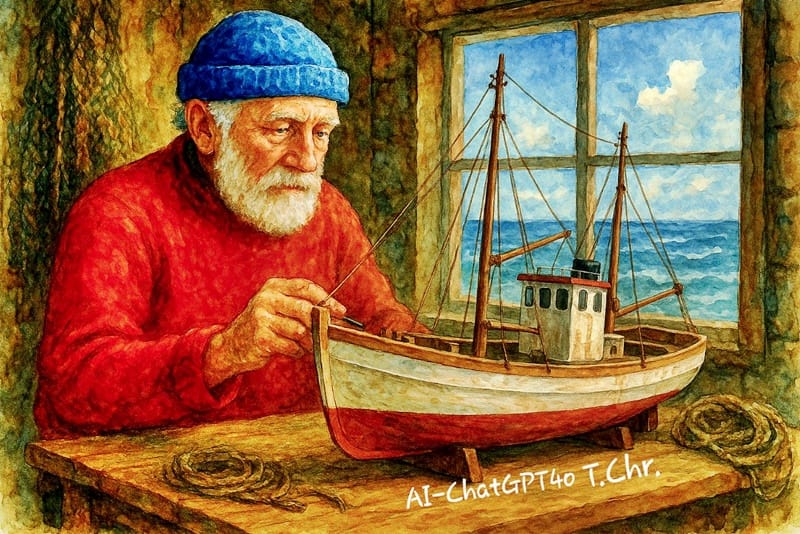

Olav’s father, Kristoffer, was a stern but fair man, known across the coast for braving the winter storms to haul in cod when others stayed ashore. Olav idolized him. As a boy, he would sit bundled in wool, watching his father mend lines in the nett shed, the same spot where Olav now sits as an old man, painting a model of his final boat—the Anna Kristina, named after his late wife.

His youth was shaped not only by the sea but by history. When the German occupation of Norway began in 1940, Olav was just ten. The small village suddenly became a strategic outpost. Armed German soldiers came, and nets were sometimes slashed in the night. His father refused to fish for the occupiers, risking arrest. Once, Olav helped hide a British radio wrapped in oilskin beneath a false plank in a fish barrel. For years, he carried the memory of seeing a local boy taken by the Germans and never returning. The sea offered no protection from war.

When peace finally came, it returned slowly. Fishing boats were rebuilt. Sons came home; some didn’t. At sixteen, Olav went to sea full-time. By twenty-five, he captained his own trawler. The ocean had made him strong, and the silence of those early mornings—net cast, sky dim, coffee hot—had made him wise. He married Anna Kristina, the daughter of a lighthouse keeper, and they raised three children near the same shore where he’d grown up.

The decades passed with salt and wind. He taught his sons the ropes and watched the fishing industry change—engines replaced sails, sonar replaced instinct, but Olav’s love for the sea never changed. He retired reluctantly in his seventies, selling his trawler, yet he always returned to the nett shed, where his hands found purpose in model boats and ropework.

Now, in his wool cap and red sweater, the old fisherman spends his days building a perfect miniature of his beloved Anna Kristina. Outside the shed window, the waves roll in like they always have—small, frothy, and eternal. His hands tremble slightly as he paints the wheelhouse white, but his eyes are clear. He doesn’t speak much anymore, but in the hush of his workshop, the past lives on in wood and memory.

The model he carves is not just a boat—it’s a lifeline, a legacy, and a farewell to a life shaped by hardship, honor, and the hum of the sea.

The old net shed still stood, though its beams groaned with age and salt. Set back from the bluff, just above the shingle beach where the tide hissed in and out like a tired breath, it had been Olav Vik's second home for seventy years. Today, a weak sun spilled through the salt-smeared window, lighting the weathered table where Olav, now ninety-four, hunched over a half-built wooden model of his last fishing trawler, the Anna Kristina.

He worked slowly. His hands were not as quick as they once were, but they were steady. Each curve of the hull, each mast, each tiny winch was a memory carved in pine. To anyone else, it might seem like a hobby—an old man passing time. But to Olav, this was resurrection.

He had been born on Ytterøyane, a cold-swept island battered by the North Atlantic, in the winter of 1931. The island had no trees then, only gnarled brush and the roar of wind that never stopped. His father fished the banks off Nordfjord, and Olav, the eldest of four, followed by age ten. By fifteen, he could gut a cod faster than his uncle and steer through fog with only the sound of breakers as his compass.

But it was the war that marked him.

When the Germans occupied Norway in 1940, their boots darkened even the remotest docks. The lighthouse on Ytterøyane became a watchtower. Their boats were inspected, their radios confiscated, and everything whispered. Olav’s father, Lars, joined the underground resistance. Young Olav became the look-out, the errand boy, the one who could run without being questioned. He was caught once—barefoot in the snow with a roll of coded notes hidden in a fish head—but the soldier let him go, thinking him simple.

The war was everywhere—even in the waves. In 1942, Olav and his father spotted the first corpse: a young British sailor, blue-lipped and tangled in kelp, washed ashore with his boots still laced and a service pistol strapped to his waist. They buried him in silence and marked the spot with stones. After that, the sea brought more: wooden crates with bloated biscuits and tins of corned beef, blackened oil drums bobbing among seaweed, a single broken lifeboat etched with "Liverpool" that carried nothing but a child’s shoe and a shattered oar.

Once, a torpedoed merchant ship went down within earshot. The islanders heard the explosion like a god slamming his fist on the table. The sky burned orange and black. By dawn, the sea was a graveyard of twisted metal and lifeless men. Olav and his father helped fish out three survivors. One was delirious, clutching a photo of his wife and child. He stayed with them for a week before a smuggled boat spirited him south.

There were darker days still. A boat from the village, accused of helping resistance fighters, was machine-gunned mid-channel. Olav’s cousin Anders was among the dead. His mother tore at her hair when the news came.

But amidst the fear, there was fire too. Defiance. They passed messages in fish barrels, hid radios beneath nets, and rowed across fjords under moonless skies. Olav learned to read Morse with his ears and carve signal codes into driftwood.

In early May 1945, word came like thunder across the sea: the Germans were retreating. By the 8th, British ships appeared on the horizon, their grey hulls slicing the swells like knives of salvation. Olav had never seen such vessels—massive, bristling with antennas, flags snapping in the wind. The village erupted in tears and cheers.

One Allied sailor, tall and freckled, tossed Olav a ration bar and saluted. It tasted of chocolate and freedom.

After the war, the sea seemed calmer. Or maybe he had grown harder. He bought his first boat with reparation money and fished alone until he met Anna Kristina Nygaard in the summer of 1952. She came to the island as a schoolteacher, fresh out of Bergen, with red mittens and a smile that silenced him like a dropped anchor.

Their first conversation was at the Midsummer bonfire. He asked if she feared the ocean. She said, "No. It sings to me."

They married a year later. He named his new boat after her. The Anna Kristina was longer, stronger, diesel-powered and white-hulled. It became a legend along the coast. So did they.

Anna gave him two daughters and a son. She ran the schoolhouse and organized concerts, knitting drives, and rescue funds for stranded sealers. But most of all, she was his harbor. When he returned from weeks at sea, it was her voice through the fog, her tea waiting on the stove, her arms that still fit around his waist like no storm ever could.

In 1987, Anna died of cancer. He never took another woman to his bed. The boat continued on, but something in him cracked. He fished less. He came ashore more often. Eventually, he retired and began carving small models to keep his hands busy. But none matched the devotion he poured into this last one.

The Anna Kristina model was nearly done now. Through the window, the ocean stretched to the far edge of the world, flecked with foam. He could still hear her voice sometimes in the wind—especially when the sky turned grey and the gulls cried high.

He placed the tiny nameplate under the bow, painted in red. His hands lingered.

The light shifted. Olav stood, slower than he once did, and stepped to the window. A gust rattled the old shed, but inside it was warm. On the table, the miniature trawler stood proud, rigged and weathered, as if ready to be launched into memory.

Outside, the tide had turned.

He whispered, "She sings to me too, Anna. She always did."

And then he sat, letting the hush of the sea wrap him in its timeless arms, as the last boat he would ever build stood finished by his side.

That night, the wind picked up, just as it had on so many fishing nights of his youth. But Olav stayed in the shed long after dusk. He lit the old kerosene lamp—Anna’s lamp—and laid out her faded red mittens on the bench beside him. For years, they had remained tucked in a drawer, their wool stiff and faded but still whole. He placed one on the tiny steering wheel of the boat, as if she were still there.

He remembered their last trip together before she fell ill. It had been a short voyage to Lofoten in the spring of 1985, a journey more for memory than for catch. Anna stood beside him at the wheelhouse, wrapped in her seal coat, her eyes scanning the horizon. "Promise me," she had said, "when you're too old to fish, you’ll build her again. So we can keep sailing."

He had laughed then, kissed her forehead. "Only if you promise to meet me at the helm."

He hadn’t forgotten.

Back inside the shed, the cold crept into his bones, but Olav didn’t mind. He pulled a wool blanket over his knees and sat before the boat, whispering sea shanties, half-sung, half-murmured, songs Anna used to hum while hanging clothes in the wind.

Outside, the moon broke through the clouds. The sea, always awake, lapped gently at the rocks. And inside the old shed, between the smell of pine shavings and brine, an old man and his memories floated once more.

Tomorrow, perhaps, he would take the model to the village museum, as promised. Or perhaps he would wait a little longer.

The Anna Kristina was ready. But Olav was not quite finished sailing.

A Net Shed Full of Memory – The Philosophy of Olav’s Life

In the quiet solitude of an old net shed, with sunlight pooling across salt-worn timber and the distant sound of waves licking the shore, an old man leans over his table, crafting a model of his final boat. It is more than wood and paint—it is memory, grief, and meaning shaped by calloused hands. Olav is not simply building a trawler; he is recreating the vessel of his identity, a monument to the life he lived and the truths he learned in the tides of love, war, and work.

He was born into the sea, on a North Atlantic island where existence was hard and deeply tied to nature’s indifference. In that crucible, he learned early that life is both gift and trial—that joy is always edged by danger, and that survival, like fishing, demands patience, resilience, and trust in forces larger than oneself.

The war intruded on this elemental life, not with ideology, but with death washing ashore. The sea became a messenger of horror—corpses, shattered boats, drifting crates from sunken freighters. Yet even then, in those darkest hours, Olav discovered the duality of the human condition: how courage and cruelty, despair and hope, could occupy the same waters. The sea taught him that even wreckage floats—and that even in destruction, something human can be salvaged.

Love, too, entered his life in the form of Anna Kristina. She was not merely a companion, but a mirror. Through her, Olav saw what it meant to anchor oneself to another soul. In her laughter and strength, he found the balance the sea had denied him. But love was not a harbor free of storms—it required sacrifice, quiet endurance, and a deep commitment to presence. Their bond, forged in war and weathered through decades, embodied what the philosopher Søren Kierkegaard called the “eternal in time”—a love that matures not through passion alone, but through shared silence, rituals, and the forgiveness born of long companionship.

Now, with his hands slower and the world quieter, Olav reflects. His solitude is not loneliness—it is fullness. He does not fear death, for he has long lived with it. What he fears is forgetting, or worse, being forgotten. That is why he shapes the boat. The act is both remembrance and rebellion—a way of saying, I was here, I mattered, I belonged to the sea, and she to me.

His life is a meditation on impermanence. Boats rot, nets fray, names fade—but the essence of a life well-lived leaves a trace, not in monuments, but in the hearts of those who witnessed it, and in the simple rituals: the knot tied perfectly, the way the wood bends under pressure, the gaze across a wind-rippled fjord.

Olav’s story teaches us that the grand themes of existence—love, loss, loyalty, purpose—are not always found in cities, war rooms, or novels, but often in the humble shed of an old fisherman, among sawdust, memory, and the low eternal murmur of the sea.