“The Crimson Banner of Lord Takeshi”

By AI-ChatGPT4o-T.Chr.-Human Synthesis-20 April 2025

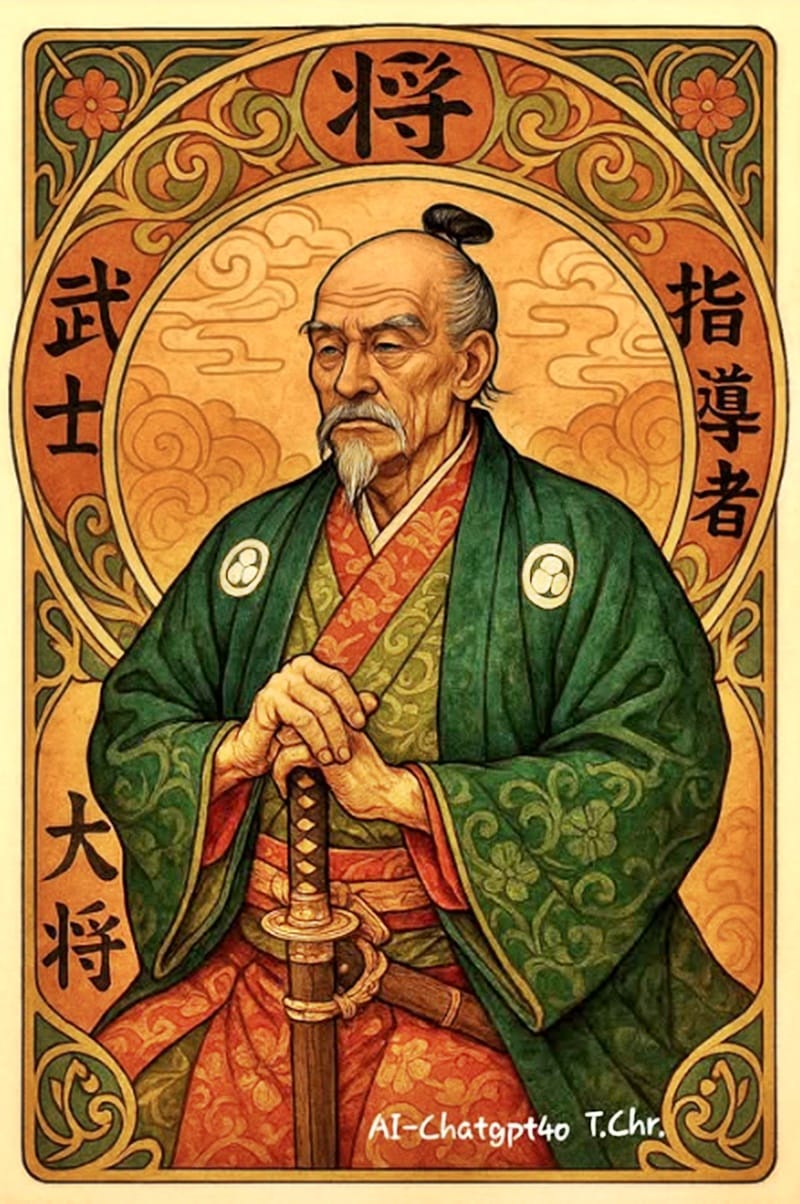

In the twilight years of the 16th century, when empires stretched across great oceans and the heavens watched in silence, there arose from the island nation of Nippon a formidable warlord whose name would echo in the chronicles of East Asia — Lord Takeshi no Yamada.

Takeshi was not born into greatness. A second son of a minor daimyo in Higo Province, he was raised amidst whispers of obscurity and shadow. But he was no ordinary boy. As a youth, he devoured the Art of War, trained beneath waterfall temples, and rose through military ranks with a sword in one hand and strategy in the other.

By 1599, while Japan convulsed with internal power struggles, Takeshi united several clans under the Crimson Banner, a symbol of fire and loyalty. He turned his gaze westward to the disunified Ming Dynasty, where corruption and rebellion weakened imperial authority. Seizing the moment, Takeshi set sail with an army of 40,000 ashigaru and samurai, a fleet of black-sailed atakebune warships crossing the Yellow Sea under cover of spring mists.

His first conquest was the port city of Ningbo. Using a brilliant feigned retreat tactic, Takeshi lured the defenders into a forested gorge and unleashed his archers from the cliffs above — a battle later immortalized in tapestries as “The Rain of Arrows.” From there, his forces surged inland, seizing Hangzhou and then Nanjing, adapting to Chinese terrain with brutal efficiency.

But Takeshi was no mere conqueror. Where he ruled, he built. He blended Japanese administrative precision with Chinese local governance, preserving rice taxes and rewarding loyalty. He adopted Chinese scholars into his court and ordered temples restored rather than razed. His vision was not of plunder, but of a new eastern empire — Nichi-Chū Teikoku, the Japanese-Chinese Empire.

The Ming court, shocked and disoriented, dispatched a legendary general named Zhao Mingyuan to stop him. The two titans clashed in 1604 at the Battle of Huai River. Takeshi, outnumbered two to one, used the terrain to encircle Zhao’s elite cavalry, then led a personal charge that broke through the imperial center. Zhao was slain in single combat — his armor cleaved by Takeshi’s ancestral blade, Kurokiba.

For seven years, Lord Takeshi ruled from a jade pavilion in occupied Luoyang, called by his allies The Eastern Shogun. Yet, his dream was cut short not by war, but by betrayal. In 1607, a deadly alliance of rival Japanese lords, fearing his rising power, poisoned his emissaries and cut off reinforcements. Stranded, Takeshi fought to the last, dying atop the ramparts of Luoyang under a burning sky, crimson banner still flying.

To this day, in some forgotten villages of eastern China, old men tell tales of the “Mountain Samurai,” and how, for one brief span of history, the dragon bowed to the rising sun.

The End