Can We Exit From a World of Debt?

By SheerPost-Vijay Prashad- March 28, 2025

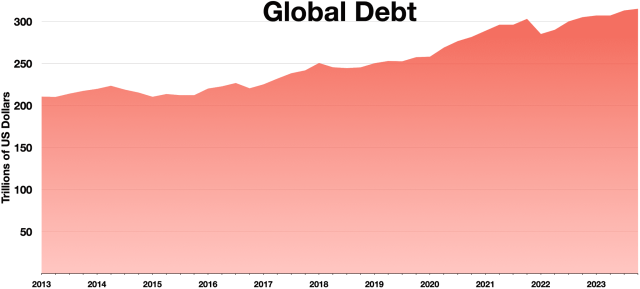

In the past two decades, the external debt of developing countries has quadrupled to $11.4 trillion (2023). It is important to understand that this money owed to foreign creditors is equivalent to 99% of the export earnings of the developing countries. This means that almost every dollar earned by the export of goods and services is a dollar owed to a foreign bank or bond holder.

Countries of the Global South, therefore, are merely selling their goods and services to pay off debts incurred for development projects, collapsed commodity prices, public deficits, the COVID-19 pandemic, and the inflation due to the Ukraine war. Half the world’s population (3.3 billion) lives in countries that allocate more of their budget to pay off the interest on debt than to pay for either education or health services. On the African continent, of the fifty-four countries, thirty-four spend more on debt servicing than on public healthcare. Debt looms over the Global South like a vulture, ready to pick at the carcass of our societies.

Why are countries in debt? Most countries are in debt for a few reasons:

- When they gained independence about a century ago, they were left impoverished by their former colonial rulers.

- They borrowed money for development projects from their former colonial rulers at high rates, making repayment impossible since the funds were used for public projects like bridges, schools, and hospitals.

- Unequal terms of trade (export of low-priced raw materials for import of high-priced finished products) further exacerbated their weak financial situation.

- Ruthless policies by multilateral organisations (such as the International Monetary Fund – IMF) forced these countries to cut domestic public spending for both consumption and investment and instead repay foreign debt. This set in motion a cycle of low growth rates, impoverishment, and indebtedness.

Caught in the web of debt-austerity-low growth-external borrowing-debt, countries of the Global South almost entirely abandoned long-term development for short-term survival. The agenda available to them to deal with this debt trap was entirely motivated by the expediency of repayment and not of development. Typically, the following methods were promoted in place of a development theory:

- Debt relief and debt restructuring. Seeking a reduction in the debt burden and a more sustainable management of long-term debt payments.

- An appeal for foreign direct investment (FDI) and an attempt to boost exports. Increasing the ability of countries to earn income to pay off this debt, but without any real change to the productive capacity within the country.

- Cuts to public spending, largely an attrition of social expenditure. Shifting the fiscal landscape so that a country can use more of its social wealth to pay off its foreign bold holders and earn ‘confidence’ in the international market, but at the expense of the lives and well-being of its citizens.

- Tax reforms that benefited the wealthy and labour market reforms that hurt workers. Tax cuts to encourage the wealthy to invest in their society – which very rarely happens – and a change in trade union laws to allow greater exploitation of labour to increase capital for investment.

- Institutional reform to ensure less corruption by greater international control of financial systems. To open the budgetary process of a country to international management (through the IMF) and allow foreign economists to control the fiscal decision-making.

Each of these approaches separately and all of them together provided no assessment of the underlying problems that produced debt, nor did they offer a pathway out of debt dependency.

Effectively, if this is the best approach available, then developing countries need a new development theory.

A New Development Theory

It is by now understood that the entry of FDI and the export of low-priced commodities do not by themselves increase the gross domestic product (GDP) of a developing country. Indeed, FDI – in an age of financial liberalisation and without capital control – can create enormous problems for a poor country since the money can operate to destabilise the economy. The latter requires long-term investments rather than hot-money transactions.

Research by Global South Insights (GSI) and Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research shows that it is not FDI that increases GDP over long periods, but that there is a high correlation between an increase in net fixed capital investment and GDP growth (net fixed capital investment is the increased spending on capital stock above depreciation). In other words, if a country invests money to increase its capital stock, it will see a secular rise in its growth rate.

That is the reason why countries such as China, Vietnam, India, and Indonesia have sustained high growth rates in a period when most countries (illustratively in the Global North) have had low to negative growth rates (particularly when considering rising inflation). Even the World Bank agrees that the exit from the ‘middle-income trap’ is to increase investment, infuse technologies from abroad, and innovate technologies internally (they call it the ‘3i method’). At the heart of the project must be an increase in net fixed capital investment.

Our research shows that as GDP grows, life expectancy rises as well. There are many elements here that require investigation: for instance, if the quality of GDP growth improves (more industry, better social spending), what does this do for social outcomes? To talk about the quality of GDP is to raise issues of allocation of social wealth into specific sectors, which brings up the importance of both robust economic planning and proper fiscal policy that is not motivated by paying off foreign bondholders but by building the net fixed capital in a country over the long-term.

But how does one get the finance to both service debts and build capital stock? That is not an impossibility since most developing countries are rich in resources and solely need to build the power to marshal those resources. The answers might be found less in the laws of economics than in the unequal relations of power in the world. With the churning of the global order, there might now be an opportunity to create new financial strategies for development.

The basis of a conversation about development theory should not be how to sustain an economy in a permanent debt spiral that leads to deindustrialisation and despair. It should instead be about how to break that cycle and enter a period of industrialisation, agrarian reform, growth, and social progress. It is this insight that motivates us to begin a fresh conversation, not about the need for this or that economic policy to salvage a bad situation, but for a new development theory altogether.

This article was produced by Globetrotter and No Cold War.

Please share this story and help us grow our network!

Vijay Prashad

Vijay Prashad is an Indian historian, editor and journalist. He is a writing fellow and chief correspondent at Globetrotter. He is an editor of LeftWord Books and the director of Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research. He is a senior non-resident fellow at Chongyang Institute for Financial Studies, Renmin University of China. He has written more than 20 books, including The Darker Nations and The Poorer Nations. His latest books are Struggle Makes Us Human: Learning from Movements for Socialism and (with Noam Chomsky) The Withdrawal: Iraq, Libya, Afghanistan, and the Fragility of U.S. Power. Author Site