THE LIFE OF FYODOR DOSTOEVSKY.

By ChatGPT4o-T.Chr.-Human Synthesis-12 January 2025

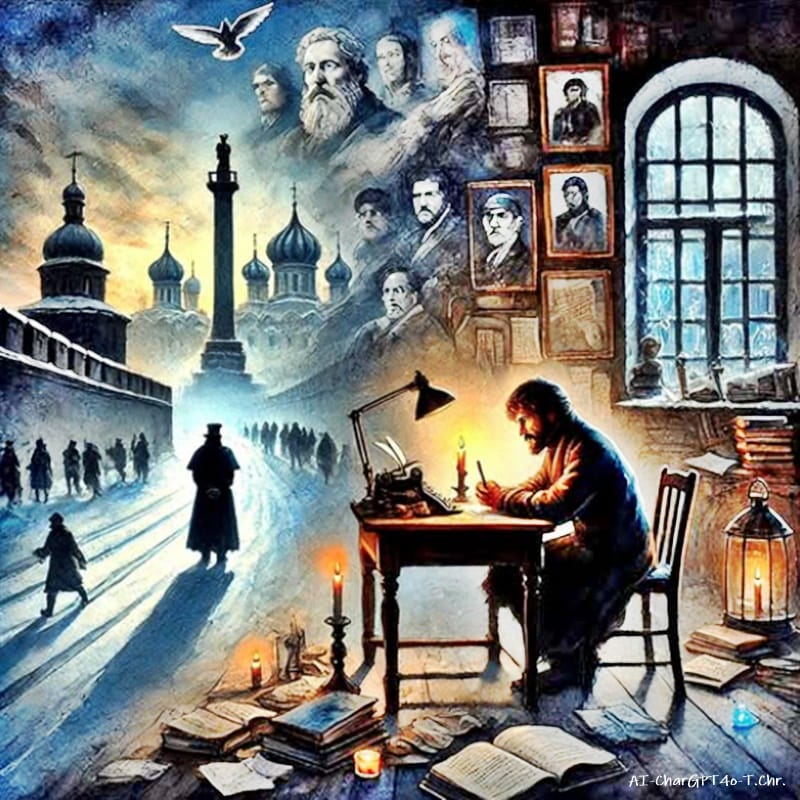

Fyodor Dostoevsky’s life was a symphony of chaos and brilliance, a story of a man who danced with demons and somehow emerged as one of the greatest writers the world has ever known.

Born into a family more familiar with hardship than comfort, young Fyodor found solace in books, weaving dreams of strange characters and darker realities even as his world fell apart around him. Orphaned and alone, he drifted from one place to another, learning early the bitter taste of survival.

In his youth, Fyodor wasn’t the sort to follow the rules. School bored him. The structured world of academia couldn’t compete with the wild terrain of his imagination. He preferred wandering the streets, watching the broken and the proud, listening to whispers of despair and hope.

It wasn’t long before he moved to St. Petersburg, a city that seemed to echo his own contradictions: elegant and grimy, brilliant and brooding. There, he wrote Poor Folk, a novel so heartbreakingly raw that it turned him into an overnight sensation. For a fleeting moment, Fyodor was a star.

But fame was a fickle friend. Fyodor’s life unraveled as quickly as it had come together. He developed a dangerous relationship with gambling, not just a vice but a kind of addiction that mirrored his relentless probing into the extremes of human behavior. He lost money, his possessions, even his dignity, chasing the impossible dream of beating the odds.

And then came the arrest. Caught associating with a group of political dissidents, he was sentenced to a mock execution, followed by years of hard labor in Siberia. It was here, in the frozen wasteland, that he truly began to understand suffering—not just as an idea, but as a living, breathing force.

Fyodor Dostoevsky's time in Siberia marked one of the most transformative and grueling periods of his life. Arrested in 1849 for his involvement with the Petrashevsky Circle, a group of intellectuals discussing liberal and socialist ideas, Dostoevsky was sentenced to death by firing squad. However, at the last moment, the sentence was commuted to four years of hard labor in a Siberian penal camp, followed by compulsory military service. This harrowing ordeal, beginning with the mock execution, profoundly shaped his psyche and future work.

Life in the Omsk Penal Colony

Dostoevsky arrived at the prison in Omsk, Siberia, in January 1850. The conditions he encountered were almost beyond endurance. The barracks where he lived were wooden huts, overcrowded with convicts from various backgrounds, including common criminals, murderers, thieves, and political prisoners like himself. Privacy was nonexistent, and the air inside was stifling, filled with the stench of sweat, filth, and rotting food.

The physical environment was equally punishing. Winters were bitterly cold, with temperatures plummeting far below freezing, while summers brought swarms of insects and oppressive heat. Basic hygiene was impossible. Lice were a constant plague, and illnesses such as scurvy and dysentery were rampant. Meals were meager and monotonous, consisting of black bread and thin soup, often insufficient to stave off hunger.

Hard Labor and Routine

Every day was marked by relentless physical labor. Dostoevsky and his fellow inmates were tasked with exhausting work, such as breaking stones, shoveling snow, or hauling timber. The monotony of the labor was matched by the unrelenting discipline of the guards, who maintained strict and often brutal order. Any infraction, real or perceived, was met with harsh punishment, including flogging or confinement in even harsher conditions.

Despite the brutality, Dostoevsky was acutely aware of the humanity around him. He observed the intricate dynamics among the prisoners—acts of kindness and camaraderie juxtaposed with cruelty and selfishness. He wrote later that he found some of the most profound truths about human nature in those years of deprivation, observing how individuals reacted under extreme duress.

Spiritual Awakening and Growth

Amid this suffering, Dostoevsky experienced a profound spiritual awakening. The only book he was allowed to keep was a New Testament, given to him by the wife of one of the Decembrists he encountered on his journey to Siberia. He read it obsessively, finding solace and meaning in the teachings of Christ. This marked a turning point in his life, as his earlier political idealism gave way to a deeply personal understanding of suffering, redemption, and the human condition.

Siberia became for Dostoevsky not only a place of punishment but also a crucible of spiritual and psychological transformation. He began to see suffering as a path to salvation, an idea that would become central to his later works. The themes of sin, guilt, and redemption found in Crime and Punishment, The Brothers Karamazov, and other novels trace their roots to this period.

Human Connections and Observations

Although he was largely isolated from his family and friends during his time in Siberia, Dostoevsky formed complex relationships within the prison. He studied the personalities and stories of his fellow inmates, noting their moral struggles, their capacity for both evil and goodness, and their resilience in the face of suffering. These observations provided him with a deep reservoir of material that he would later draw upon to create some of the most vivid and psychologically intricate characters in literature.

Aftermath and Lasting Impact

When Dostoevsky was released from the penal colony in 1854, he was a changed man. Though scarred physically and emotionally, he carried with him a newfound sense of purpose. His belief in the possibility of redemption through suffering and his insight into the complexities of human nature became central to his writing. The Siberian experience infused his work with a moral intensity and existential depth that resonated far beyond his own time.

Siberia, with its relentless hardships and stark beauty, became an indelible part of Dostoevsky’s life and art. It was here that he truly came to understand the paradoxes of human existence: the capacity for cruelty and compassion, despair and hope, sin and redemption. These insights, born from years of extreme suffering, would form the foundation of some of the greatest novels in world literature.

Fyodor returned to the world scarred but wiser. His stories grew darker, his characters richer, his themes more profound. He married Anna, a young stenographer who saw through the chaos and loved the man underneath.

Anna was his anchor, transcribing his fevered words, selling his works, and managing their household through storms of debt and fleeting successes. Together, they built something fragile but real: a family, a semblance of stability, a partnership that somehow endured even as Fyodor continued to wrestle with his gambling and his health.

Through it all, Fyodor wrote with a fury that bordered on obsession. Crime and Punishment was his exploration of guilt and redemption. The Idiot examined innocence in a world that crushed it.

The Brothers Karamazov took on the vastness of faith, doubt, and familial bonds. Each novel was a testament to his belief that the human soul was both abyss and salvation, a battlefield where good and evil endlessly warred.

In his final years, Fyodor became a legend. He traveled Europe, spoke to crowds, and was celebrated as a literary giant. But his health faltered, and the shadows of his past never fully released their grip. When he died, it wasn’t as a broken man but as one who had wrung every ounce of meaning from a turbulent life.

Fyodor Dostoevsky’s story is not one of triumph in the traditional sense. It is a story of struggle, resilience, and the relentless pursuit of truth. He delved into the darkest corners of existence not to despair but to illuminate the beauty hidden there. His life was his art, and his art, a mirror to the soul.

Even in death, Dostoevsky’s presence lingers, like the echo of a haunting melody. His work did more than entertain—it reached into the depths of the human condition, turning pain and doubt into a universal language.

His characters, from the tormented Raskolnikov to the idealistic Prince Myshkin, are not just figments of imagination but reflections of ourselves: flawed, yearning, struggling to find meaning in a chaotic world.

His writing dared to ask the questions most of us are too afraid to confront. What does it mean to be truly free? Can suffering be redemptive? Is faith a crutch, or is it the very thing that saves us?

Dostoevsky never offered easy answers. Instead, he forced readers to grapple with the paradoxes of existence, to sit with the discomfort of their own humanity. It’s why his work feels timeless, as relevant in the bustling modern world as it was in the cobblestone streets of 19th-century Russia.

Dostoevsky’s legacy is not simply in the pages of his books but in the way he changed literature forever. He blurred the lines between storytelling and philosophy, between character and conscience.

He gave voice to the silenced, dignity to the broken, and hope to those lost in despair. His novels are not just stories—they are experiences, invitations to step into the shoes of another and see the world through their eyes.

In the end, Fyodor Dostoevsky’s life was not a tale of perfection or even redemption. It was a testament to the power of perseverance and the human spirit’s capacity to create beauty from chaos.

His journey reminds us that genius often walks hand in hand with struggle, and that the darkest paths can lead to the most profound truths. To read Dostoevsky is to confront the rawness of life, to feel deeply, and to think expansively. It is to understand that, no matter how broken we may feel, there is always something within us that remains unbroken.

Through his words, Fyodor Dostoevsky continues to speak, a voice calling out across the years, reminding us to search for meaning, embrace our flaws, and never stop questioning the world—or ourselves.

Dostoevsky’s life and work stand as a testament to the paradox of human existence: that from suffering can emerge understanding, from despair can rise beauty, and in the chaos of life lies the potential for transcendence.

He explored the depths of human frailty and ambition, grappling with questions of morality, faith, and identity that remain as vital today as they were in his time. Through his characters and their struggles, Dostoevsky showed us that the human soul is a battlefield where darkness and light, doubt and belief, endlessly collide.

His philosophy teaches us that life is not a pursuit of perfection but a journey through contradiction. We are, like his protagonists, torn between our highest ideals and our basest instincts. And yet, it is this very tension—the clash of opposites—that defines us, propelling us toward growth, understanding, and ultimately, meaning.

Dostoevsky did not offer comfort or resolution; he offered truth. His works confront us with the reality that suffering is inevitable, but within it lies the potential for transformation. Redemption is not found in escaping pain but in facing it, questioning it, and allowing it to shape us.

His faith in the resilience of the human spirit serves as a reminder that even in our darkest moments, we possess the capacity to rise, to love, and to create.

In the end, Dostoevsky’s message is one of profound hope—not in the absence of struggle, but in the possibility of finding purpose within it. Life, he reminds us, is a mystery to be lived, not a problem to be solved.

And perhaps it is in embracing the mystery, in seeking understanding despite uncertainty, that we truly become alive.

The End