How I Learned To Love The New World Order (1992)

On April 23, 1992, the Wall Street Journal published an article (read below) by Joe Biden titled, “How I Learned to Love the New World Order,” in which Biden reveals his allegiance to the agenda.

American President Joe Biden wrote in January 25, 1992 a lengthy piece published in the Wall Street Journal in which he explains how he learned to love the New World Order.

As GreatGameIndia reported earlier, Joe Biden’s great grandfather worked for the East India Company. Not many are aware that after the so called dissolution of the British Empire, the company just went underground and resurfaced with new identities. It is known by many names – Empire 2.0, the Deep State, the Hidden Hand, the New World Order etc.

Below we publish the article in full penned by Joe Biden in 1992 for the education of our readers.

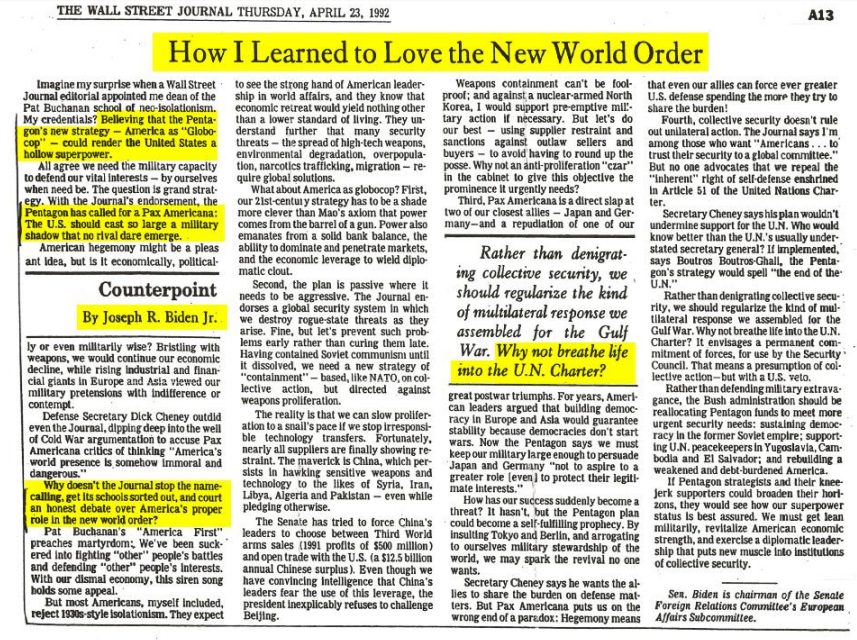

How I Learned to Love the New World Order

Biden, Joseph R Jr. - Wall Street Journal. New York, N.Y.: Apr 23, 1992.

Joseph R. Biden Jr defends his view that the Pentagon’s new strategy which appoints the US as a sort of world monitor could render the US a hollow superpower. Biden explains why he reacted the way he did to the plan.

Imagine my surprise when a Wall Street Journal editorial appointed me dean of the Pat Buchanan school of neo-isolationism. My credentials? Believing that the Pentagon’s new strategy — America as “Globocop” — could render the United States a hollow superpower. All agree we need the military capacity to defend our vital interests — by ourselves when need be. The question is grand strategy. With the Journal’s endorsement, the Pentagon has called for a Pax Americana: The U.S. should cast so large a military shadow that no rival dare emerge.

American hegemony might be a pleasant idea, but is it economically, politically or even militarily wise? Bristling with weapons, we would continue our economic decline, while rising industrial and financial giants in Europe and Asia viewed our military pretensions with indifference or contempt.

Defense Secretary Dick Cheney outdid even the Journal, dipping deep into the well of Cold War argumentation to accuse Pax Americana critics of thinking “America’s world presence is somehow immoral and dangerous.

” Why doesn’t the Journal stop the namecalling, get its schools sorted out, and court an honest debate over America’s proper role in the new world order?

Pat Buchanan’s “America First” preaches martyrdom: We’ve been suckered into fighting “other” people’s battles and defending “other” people’s interests. With our dismal economy, this siren song holds some appeal.

But most Americans, myself included, reject 1930s-style isolationism. They expect to see the strong hand of American leadership in world affairs, and they know that economic retreat would yield nothing other than a lower standard of living. They understand further that many security threats — the spread of high-tech weapons, environmental degradation, overpopulation, narcotics trafficking, migration — require global solutions.

What about America as globocop? First, our 21st-century strategy has to be a shade more clever than Mao’s axiom that power comes from the barrel of a gun. Power also emanates from a solid bank balance, the ability to dominate and penetrate markets, and the economic leverage to wield diplomatic clout.

Second, the plan is passive where it needs to be aggressive. The Journal endorses a global security system in which we destroy rogue-state threats as they arise. Fine, but let’s prevent such problems early rather than curing them late. Having contained Soviet communism until it dissolved, we need a new strategy of “containment” — based, like NATO, on collective action, but directed against weapons proliferation.

The reality is that we can slow proliferation to a snail’s pace if we stop irresponsible technology transfers. Fortunately, nearly all suppliers are finally showing restraint. The maverick is China, which persists in hawking sensitive weapons and technology to the likes of Syria, Iran, Libya, Algeria and Pakistan — even while pledging otherwise.

The Senate has tried to force China’s leaders to choose between Third World arms sales (1991 profits of $500 million) and open trade with the U.S. (a $12.5 billion annual Chinese surplus). Even though we have convincing intelligence that China’s leaders fear the use of this leverage, the president inexplicably refuses to challenge Beijing.

Weapons containment can’t be foolproof; and against a nuclear-armed North Korea, I would support pre-emptive military action if necessary. But let’s do our best — using supplier restraint and sanctions against outlaw sellers and buyers-to avoid having to round up the posse.

Why not an anti-proliferation “czar” in the cabinet to give this objective the prominence it urgently needs?

Third, Pax Americana is a direct slap at two of our closest allies — Japan and Germany — and a repudiation of one of our panel1. Rather than denigrating collective security, we should regularize the kind of multilateral response we assembled for the Gulf War. Why not breathe life into the U.N. Charter? great postwar triumphs.

For years, American leaders argued that building democracy in Europe and Asia would guarantee stability because democracies don’t start wars. Now the Pentagon says we must keep our military large enough to persuade Japan and Germany “not to aspire to a greater role even to protect their legitimate interests.

”

How has our success suddenly become a threat? It hasn’t, but the Pentagon plan could become a self-fulfilling prophecy. By insulting Tokyo and Berlin, and arrogating to ourselves military stewardship of the world, we may spark the revival no one wants.

Secretary Cheney says he wants the allies to share the burden on defense matters. But Pax Americana puts us on the wrong end of a paradox: Hegemony means that even our allies can force ever greater U.S.

defense spending the more they try to share the burden!

Fourth, collective security doesn’t rule out unilateral action. The Journal says I’m among those who want “Americans . . . to trust their security to a global committee.” But no one advocates that we repeal the “inherent” right of self-defense enshrined in Article 51 of the United Nations Charter.

Secretary Cheney says his plan wouldn’t undermine support for the U.N. Who would know better than the U.N.’s usually understated secretary general? If implemented, says Boutros Boutros-Ghali, the Pentagon’s strategy would spell “the end of the U.N.”

Rather than denigrating collective security, we should regularize the kind of multilateral response we assembled for the Gulf War. Why not breathe life into the U.N. Charter? It envisages a permanent commitment of forces, for use by the Security Council. That means a presumption of collective action — but with a U.S. veto.

Rather than defending military extravagance, the Bush administration should be reallocating Pentagon funds to meet more urgent security needs: sustaining democracy in the former Soviet empire; supporting U.N. peacekeepers in Yugoslavia, Cambodia and El Salvador; and rebuilding a weakened and debt-burdened America.

If Pentagon strategists and their kneejerk supporters could broaden their horizons, they would see how our superpower status is best assured. We must get lean militarily, revitalize American economic strength, and exercise a diplomatic leadership that puts new muscle into institutions of collective security.

Sen. Biden is chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee’s European Affairs Subcommittee.

FROM A SECOND INDIAN PAPER IN 1992

About Joe Biden, President Obama’s Secretary of Defense Robert Gates wrote: “He’s a man of integrity, incapable of hiding what he really thinks, and one of those rare people you know you could turn to for help in a personal crisis. Still, I think he’s been wrong on nearly every major foreign policy and national security issue over the past four decades.”

So far, Democratic presidential candidates have said very little about foreign policy, being largely focused on the domestic arena. However, foreign policy is where the president has nearly absolute power to send troops around the globe, launch wars—in the past 75 years at least—establish international agreements, and make trade deals.

With Trump behind the leading Democratic contenders in the polls, it is likely that a Democrat will be elected president in 2020. Biden is currently the most electable. Polls show that he is not only substantially ahead of his Democratic rivals, but that he is farthest ahead of Trump in the general election. With this being said, it is important to look at what his foreign policy is likely to be.

Despite Biden’s gaffes and weird alterations of the past, he has been regarded as quite knowledgeable on international affairs, since he served much of his time on the Senate Foreign Relations Committee. He was selected as Obama’s vice president in large measure because of his foreign affairs experience. And while hardly a Kissingeresk thinker, Biden has developed his own views on this subject upon which he is quite articulate.

Steve Clemons of the Atlantic Magazine discussed foreign policy issues with Biden toward the end of the Obama presidency. Although Clemons differed with several of Biden’s positions, he found him very knowledgeable, with firm views that he had developed over the years. Clemons wrote: “I have traveled with Biden during his vice presidential tenure to Asia and Europe, watched him interact with foreign leaders abroad and at home, and have had wide-ranging discussions with him since his Senate days on everything from the confirmation battle over John Bolton’s nomination as U.N. ambassador to how the U.S. should approach its challenges in Iraq and Afghanistan. I haven’t always agreed with Biden’s positions, but those positions have tended to follow a pattern and demonstrate a consistency of approach, analysis, and engagement that stands out—particularly when compared with many other foreign-policy players who often don’t leave clear footprints.”

In 2008, when Biden was running as Obama’s vice presidential candidate, Laura Rozen wrote a descriptive article titled “Biden’s Worldview” in Mother Jones, based on the view of a former Senate Foreign Relations committee staff member, which held that “Joe Biden firmly fits into the liberal interventionist school of thought that dominated the Democratic Party during the latter half of the 1990s through 2003. At his core, he is a man comfortable with the use of American military power, as demonstrated by the key role he played in encouraging the Clinton Administration to launch air strikes in the former Yugoslavia, setting the stage for the successful Dayton peace talks and the NATO peacekeeping mission.

Biden came of age politically in the 1970’s, when he saw first-hand what the ‘Vietnam syndrome’ did to the Democratic Party for more than a generation. . . . He recognizes that military power is but only one tool in our nation’s arsenal, and that soft power plays an equally critical role. However, he is not afraid to advocate for military power where appropriate, as he did correctly in the Balkans, to his regret in Iraq in 2002, and today when it comes to Darfur (the judgment remains out on that score).”

A similar view is presented in a recent article by Alex Ward in the popular liberal-leaning news website Vox, which states that Biden “adheres to the traditional center-left worldview espoused by most establishment Democrats, which emphasizes America’s role as a champion of democracy and human rights around the world, places high value on maintaining alliances, and sees American military power on balance as a force for good in the world.”

Ward continues: “He’s [Biden] a strong advocate of NATO and of having close relationships with America’s traditional European allies. He wants to firmly push back against Russia’s aggression. He’d like to work with Latin American countries to stamp out corruption, curb violence, and democratize the region.”

Similarly, Fred Kaplan in Slate writes: “Biden has always been a champion of the alliances that he sees as the foundation of U.S. power and values—especially NATO but also with nations in Asia and the Western Hemisphere.”

What has not been given much attention in Biden’s foreign policy is a strong element of Wilsonian idealism, which came out strongly in Biden’s attachment to the concept of the New World Order, a term that President George H.W. Bush often used during the time of the Gulf War (1991-1992), though his version was far less developed and idealistic than Biden’s would be. Biden would maintain that Bush’s term lacked clarity, which he intended to provide.

On April 23, 1992, Biden wrote an opinion piece for the Wall Street Journal entitled, “How I Learned to Love the New World Order,” in which he extolled “collective security” through the United Nations and called for a “permanent commitment of forces for use by the [UN] Security Council” to maintain global peace.

From June 29 to July 1, 1992, Biden delivered four speeches to the U.S. Senate dealing with the “New World Order.” The titles of his presentations were: “The Threshold of the New World Order: The Wilsonian Vision and American Foreign Policy in the 1990’s and Beyond;” “An American Agenda for the New World Order; Organizing for Collective Security;” and “Launching an Economic-Environmental Revolution.”

Biden asserted that “we are on the threshold of a new world order, and the present [George H.W. Bush] administration is not sure what the order is. But I would like to suggest how we might begin to reorganize our foreign policy. . . . Our current President [George H.W. Bush] and his administration have shown neither the aptitude nor the will to infuse this idea with meaning through coherent agenda for action. My theme is that we must rescue this concept from negligence and pursue an active new world order agenda.”

Biden went on to claim that “[t]he Bush administration has betrayed its own express policies and achieved, in each case a result opposite to what is both possible and necessary. Saddam’s heinous and still-dangerous regime lives on while the promise of breathing new life into world institutions of collective action has been allowed to wither.”

Given the failure of the Bush administration to pursue a bona fide New World Order, Biden held that it was imperative that “the Gulf War’s ambiguous outcome not be allowed to jeopardize the momentous concept the President associated with the war.” Biden urged that that the “concept of the new world order” be rescued from “cynicism,” and “become the organizing principle of American foreign policy in the 1990’s and into the next century.”

Biden glorified Woodrow Wilson’s effort to establish a fundamentally new U.S. foreign policy relevant to the 20th century, jettisoning America’s traditional non-interventionist position vis-à-vis Europe and consequent avoidance of “entangling alliances.” “Wilson and his followers,” Biden opined, “recognized that if a nation wished to protect itself and its way of life in the 20th century, its defenses must consist not merely in its own armed strength but also in reliable mechanisms of international cooperation and joint decision. For a world in dire need of a new order, the Wilsonian promise was sweeping: That rationality might be imposed upon chaos and that principles of political democracy, national self-determination, economic cooperation, and collective security might prevail over repression and carnage in the affairs of mankind. This was, it seemed, an idea whose time had come.” Biden viewed the failure of the U.S. to enter the League of Nations to be a tragedy of monumental proportions.

Biden saw Wilson’s goal rejuvenated at the end of World War II. “As America emerged from the Second World War, the supreme legacy of Franklin Delano Roosevelt was an economic and military superpower with a will to lead. Those in the Truman years who sought to resume Wilson’s work, the work of building a true world order brought historic statesmanship to the task—the United Nations, the World Bank, the International Monetary fund, the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade, the Marshall plan, the World Health Organization and a host of other worthy U.N. agencies, the Fulbright Exchange Program, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization the Organization of American States and later the European community—became their monuments.”

Biden asserted that it was “the duty of this generation of Americans to complete the task that Woodrow Wilson began.” He held that “[o]f all the world’s multinational institutions . . . only NATO has the ability to bring coordinated, multinational military force to bear.” [July 1 speech] And he contended that “[i]nstead of tiptoeing toward a revised mandate, NATO should make a great leap forward—by adopting peacekeeping outside NATO territory as a formal alliance mission.”

While Biden recognized that NATO was currently the best way to maintain global security, it was not optimal. He held that “to realize the full potential of collective security, we must divest ourselves of the vainglorious dream of a Pax Americana—and look instead for a means to regularize swift, multinational decision and response.”[July 1 presentation] Biden held that “[t]he mechanism to achieve this lies—unused—in article 43 of the United Nations Charter, which provides that: All members undertake to make available to the Security Council, on its call and in accordance with a special agreement or agreements, armed forces . . . necessary for the purpose of maintaining international peace and security.” In taking this position, Biden’s view gravitated toward oneworldism.

In these 1992 speeches, Biden maintained that America needed to reestablish a Wilsonian vision of a New World Order. Woodrow Wilson was still a Democrat hero in the 1990s, which is not the case today since Wilson, who grew up in the Civil War Era South, is now recognized as a staunch segregationist. Among his segregationist positions, Wilson, as president, resegregated those parts of the federal government that had been integrated in the post-Civil War era. Biden has already gotten into trouble with the Democratic base for acknowledging that he worked with Southern segregationists to pass legislation, some of which dealt with school busing for integration. It is thus doubtful that Biden and his coterie of advisors would make any mention of Wilson.

Furthermore, it is unlikely that Biden will now support much of what he expressed in the early 1990s, or even during his tenure as vice president. Antony Blinken, one of Biden’s chief foreign policy advisers going back to Biden’s time in the Senate, stated: “There’s a very stark recognition that the world has changed, we are not going back to the way we did things. There are certain basic principles that worked before and should work again, but it’s very clear that the world is different, including from when [the Obama administration] found it in 2008. We need the foreign policy for the world as we find it today and as we anticipate it for tomorrow.”

Nevertheless, Biden preaches a return to international cooperation which he, like most of the mainstream media, charges President Trump with destroying. “Donald Trump’s brand of America first,” Biden asserted in his July 11, 2019 speech, “has too often led to America alone, making it much harder to mobilize others to address the threats to our common well-being.” Actually, Allied defense spending increased by morethan 9 percent from 2016 to 2018—the largest increase is 25 years.

Central to Biden’s effort to reestablish international cooperation is a global summit meeting he would arrange with the world’s democracies, non-governmental organizations and corporations—especially high tech and social media companies—to seek a common agenda to protect their shared values.

While befriending democracies, Biden declared he “would remind the world that we are the United States of America and we do not coddle dictators.” He has charged Trump for doing just that in regard to China, Russia, and North Korea.

While it might be argued that Biden’s positions today have little to do with what he advocated in the past when the United States was considered to be in a “unipolar” world, that does not seem to be the case. While he is not going to turn over America’s military to the Security Council of the United Nations as he mentioned in his 1992 speech on collective security, he still thinks in terms of democracy and collective security, as opposed to realpolitik or non-interventionism. It is not apparent, however, that if Biden became president, he would be able to draw substantial support for his foreign policy in Congress.

COPYRIGHTS

Copy & Paste lenken øverst for Yandex oversettelse til Norsk.

WHO and WHAT is behind it all ? : >

The bottom line is for the people to regain their original, moral principles, which have intentionally been watered out over the past generations by our press, TV, and other media owned by the Illuminati/Bilderberger Group, corrupting our morals by making misbehaviour acceptable to our society. Only in this way shall we conquer this oncoming wave of evil.

Commentary:

Administrator

HUMAN SYNTHESIS

All articles contained in Human-Synthesis are freely available and collected from the Internet. The interpretation of the contents is left to the readers and do not necessarily represent the views of the Administrator. Disclaimer: The contents of this article are of sole responsibility of the author(s). Human-Synthesis will not be responsible for any inaccurate or incorrect statement in this article. Human-Synthesis grants permission to cross-post original Human-Synthesis articles on community internet sites as long as the text & title are not modified.

The source and the author's copyright must be displayed. For publication of Human-Synthesis articles in print or other forms including commercial internet sites. Human-Synthesis contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available to our readers under the provisions of "fair use" in an effort to advance a better understanding of political, economic and social issues. The material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving it for research and educational purposes. If you wish to use copyrighted material for purposes other than "fair use" you must request permission from the copyright owner.