Peggy Jones, the Forgotten Mudlark of the Thames

By AI-ChatGPT4o-T.Chr.-Human Synthesis-10 May 2025.

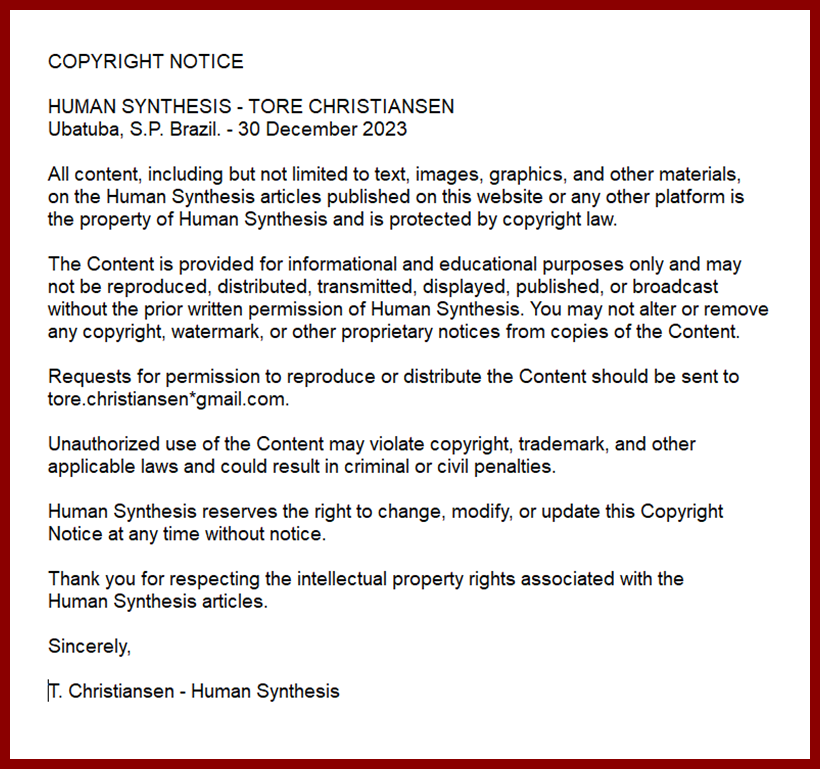

In the swirling gray mists of early 19th-century London. Where the chimneys belched soot and the cobblestones echoed with the clatter of carriage wheels, there lived a woman named Peggy Jones.

A name nearly lost to time, carried off like driftwood by the merciless tide of the River Thames. Her life was one of countless others buried beneath the grandeur of Empire, but hers echoes still, a haunting testament to survival in the shadows.

A Life in the Mud

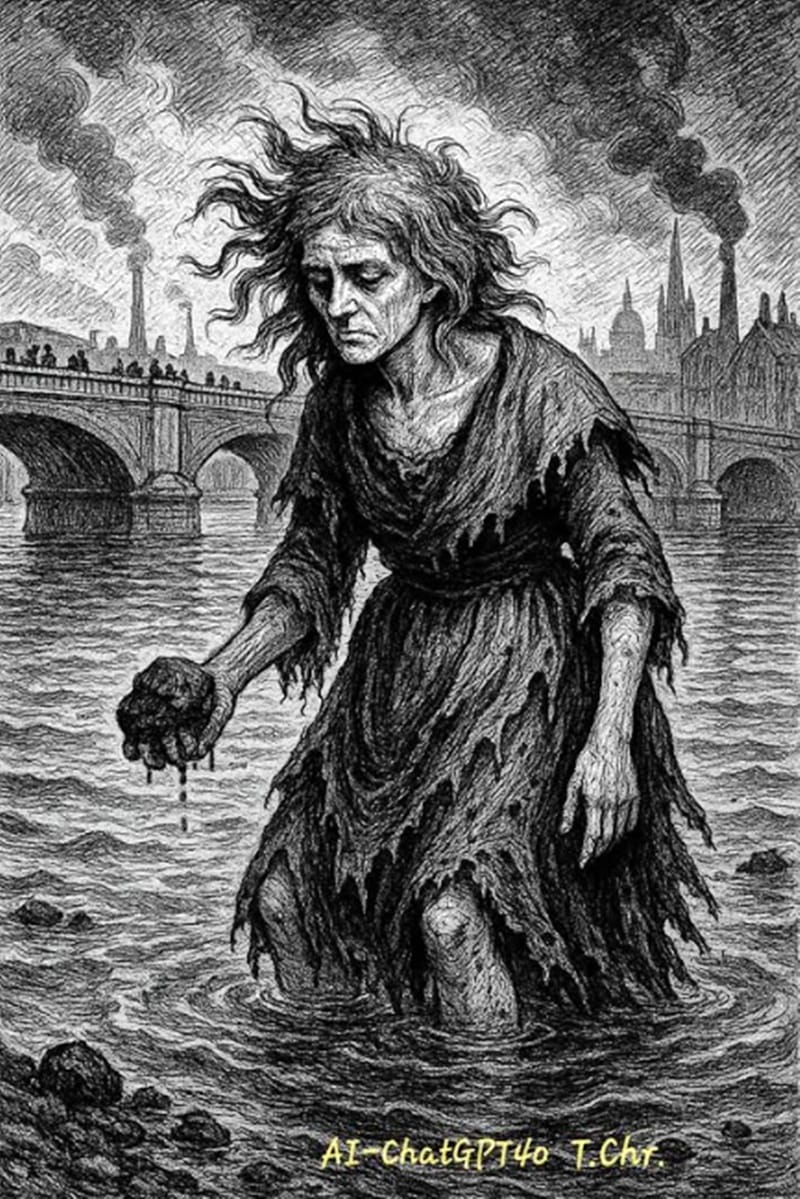

Peggy was born into poverty, though it’s doubtful even she knew the year. London in the 1800s was a city of contradictions: gleaming mansions of marble and gas-lit boulevards stood in cruel contrast to the crumbling slums of St. Giles and the rotting tenements of Chick Lane.

Disease, hunger, and despair were companions for the city’s poorest, and for women like Peggy, there were few options beyond servitude or starvation.

Instead, she turned to the river.

The Thames was no sanctuary. By then, it was already the city’s open sewer, a festering artery choked with human waste, animal carcasses, industrial runoff, and the refuse of a booming metropolis.

Yet to the mudlarks—the desperate scavengers who prowled the riverbanks—it was a lifeline. Peggy became one of them, a solitary figure wading waist-deep through the oily sludge, her feet numbed by icy water and the sharp bite of broken pottery. With her wild red hair tangled like seaweed and her petticoats soaked in filth, she became both a local spectacle and a cautionary tale.

She used her feet to feel for sunken treasures: bits of iron, lost buttons, bones, or the true prize—coal, spilled from the river barges above. The coal heavers, burly men who labored day and night hauling fuel, sometimes kicked lumps into the water when no one was looking. It was an act of silent camaraderie, a small kindness in a world that offered none.

Each handful of grit-covered coal was worth pennies. Pennies meant food—if she could find enough. More often, they bought gin. Not because Peggy was a drunk, but because the gin dulled the pain. It warmed her gut, blurred her memories, and made the biting cold of her one-room hovel on Chick Lane just barely bearable. For those on the brink, intoxication wasn’t indulgence. It was escape.

London’s Great Stain. By Peggy’s time, the Thames was already sick.

For centuries, Londoners had treated the river as both water source and sewer. But the Industrial Revolution brought pollution on a monstrous scale. Tanneries dumped caustic chemicals. Abattoirs flushed blood and entrails into the current. Human waste flowed freely from the city’s open sewers.

Cholera outbreaks raged through the slums in wave after wave. The smell in summer was so foul that Parliament itself had to shut down in 1858 during the "Great Stink," decades after Peggy had vanished. But Peggy knew no other river. To her, the Thames was not just dirty water—it was a stage, a battlefield, a marketplace, and a grave.

The poor gathered at low tide, competing for the same meager scraps. Children barely out of infancy combed the shoreline alongside the elderly and infirm. The river took as easily as it gave. One wrong step and the sucking mud could trap you. The rising tide could pull you under in moments. No one kept count of how many disappeared.

The Vanishing. In 1805, Peggy simply vanished.

There were no inquiries, no investigations. No constables knocked on doors. There were no family notices, no church bells rung. Her absence left no dent in the city’s routine. Some said the tide took her. Others whispered she died in her room, curled up on a floor of broken tiles and vermin-chewed bedding.

A few lines in a forgotten broadsheet described her only as “a drunken curiosity”—a footnote to the carnival of London life. But her life mattered.

Peggy wasn’t exceptional. That’s why her story cuts so deep. She was one of the thousands—mostly women, mostly voiceless—who clawed out an existence in the gaps left behind by prosperity.

The Empire was being built on her back and those like hers. The gleaming windows of the West End, the gas lamps of Mayfair, the polished shoes of parliamentarians—all were propped up by the invisible labor and silent suffering of people like Peggy Jones.

What the River Keeps Today, the Thames is cleaner.

Tour boats glide where barges once creaked. Joggers run along the Embankment. But it still holds its secrets. Modern mudlarks in waterproof boots now search the shore with licenses and smartphones, unearthing Roman coins, Tudor belt buckles, and even medieval shoe soles.

They share their finds on Instagram.

But no one finds Peggy.

There is no memorial, no relic, no gravestone. Her story is recovered not in artifacts, but in empathy—in the acknowledgment that the river was once a border between survival and oblivion.

Peggy’s legacy lives in the retelling, in the uneasy recognition that for every statue of a king or plaque for a general, there are hundreds of Peggys who made the city run, and who were discarded when the tide turned. The river, like history, remembers what it wants. But we can choose to remember the rest.

Peggy and the River: A Reflection

Peggy Jones was not a heroine in the traditional sense. She led no revolutions, penned no books, and left behind no portraits to hang in public halls. And yet, in her obscurity lies a profound truth: she was the city.

Not its face, but its foundation—the unseen, the walked-over, the worn-down. She was one of thousands whose lives whispered through the gutters and rippled quietly under the bridges, as the world above carried on.

The River Thames, in Peggy’s time, was a paradox—a source of life and death, of hope and decay. To the wealthy, it was a view. To the poor, it was a final chance. The river did not discriminate. It swallowed as easily as it sustained.

It offered Peggy a grim livelihood and threatened to take it away with every tide. And when she disappeared, it was as though the water had folded her back into itself, the way it had done for countless others, without ceremony or note.

Peggy’s story is not just about poverty. It is about invisibility. In a city flush with wealth and invention, her red hair and calloused hands made her a spectacle but never a person. She was seen and not known, pointed at but never protected. The true cruelty she endured was not merely the mud or cold—it was that her pain served as entertainment for those who could choose not to see it.

And the river? It mirrors the society that shaped it—flowing with grandeur above, choked with waste beneath. The Thames became a witness and a conspirator, swallowing the sins of a city that refused to claim them. Its tides masked suffering with movement, its surface ripples pretending at serenity while death and labor festered below.

Peggy’s disappearance, her unremarked end, is precisely what makes her so emblematic. She reminds us that entire civilizations are built on the backs of those never named in the histories we celebrate. And just like the river, society still has its currents—those who glide and those who drown.

Remembering Peggy is not nostalgia. It is responsibility. To look at the river today and know that it once swallowed the forgotten is to see clearly—not just into the past, but into the structures that endure. Because the Thames, like all monuments of power, has two banks: one for the admired, and one for the abandoned.

Peggy walked the mud between them.

ANOTHER IMPRESSON OF THE THAMES

June the 12th, 1796

Diary of Thomas Meeks – Riverman of Wapping

The sun rose foul this morning, casting a yellow light through the smoke that hangs always now above the river like a mourning veil. I rowed a fare from Rotherhithe to Billingsgate, and the stink was near unbearable even before the heat took hold. Dead dogs float by in the current, bloated and bobbing, their bellies puffed like drowned pigs. We passed two in an hour, and a child's doll tangled in tar-black reeds that looked more corpse than toy.

The water is thick as broth, green-brown, with scum drifting atop like stew left too long. I daren’t put my hand in it. They say it’ll draw sickness through the skin. I believe it. My cousin took to emptying the privy into the river at night like the rest, and he’s been coughing blood for a week.

At the wharves, the cranes creak and groan, lowering barrels of molasses and sacks of sugar as rats scramble beneath, bold as dockers. A ship from the Indies unloaded this morning—rich men come to claim goods while barefoot boys roll hogsheads through sludge thick with rum and blood. The dockside runs with filth when the tide’s low. When it comes in, it carries everything away, only to deposit it again a mile downstream.

And still they draw water from it! Pipes pulling poison straight into houses in Westminster. The Thames gives and takes, they say—but these days it gives mostly death.

By night, the fog crept in so heavy I near lost my bearings by Tower Stairs. The lanterns on the quayside glow dim behind soot and mist. A woman cried out in the fog—I rowed faster, head down. Best not to meddle after dark.

They say the river remembers. If it does, God help us all, for it has much to remember and little to forgive.

The End